The Muse of Song

How and why poetry should be sung to the lyre

Like Moldbug’s reservations, this project to restore traditional poetry is wholly unqualified, which means that its author can lay no claim whatsoever to formal credentials or proven expertise in the subject. My writings are pitched to those who can discern the potential of the idea through the shortcomings of its presentation, and (hopefully) take up the former in order to improve upon the latter. Think of me, if you must, as a dwarven smith hammering away at tradpoetry so that others may one day wield it with true finesse and power.

I stress all of this because we are now approaching the topic of music, on which my unqualification comes close to outright ignorance. Yet there is no avoiding this topic, because there is no restoring traditional poetry without reconciling verse with song. And I must not only theorize about it, but also to demonstrate a musical technique, worked out by one part research and three parts trial-and-error.

This technique involves singing poetry to the lyre. Although song and lyre have long been in use as traditional metaphors for the work of the poet, it has been a very long time since they were last taken literally (or rather, perhaps, unliterally). Perhaps, then, before we make any inquiries as to how poetry should be sung to the lyre, we should spend some words on the question of why.

The answer is that poetry without music, such as we know it today, is like a frog forced out of water or a bouquet severed from the bush. In this case, the onset of desiccation and death was not instant, and there was a long period of decadent efflorescence in which new arrangements and refinements were made to poetry within the glass vessel of literature. Now that this has passed1, poetry is disintegrating into a formless and meaningless word salad, forced to become ever more impenetrable because it must never repeat anything. Mere literary formalism cannot be expected to reverse this decay; meter, ornamentation and repetition all belong to music and have no essential ground in literature.

Some might object that, if the musical element of poetry has been lost, then it must have died out for good evolutionary reasons. But poetry has not ‘evolved’ towards higher standards in the same way as medicine, technology or even premodern visual art. It would be more accurate to say that it has adapted to conditions of ever-increasing literacy, under which written works could reach wider and last longer than musical performances. It might have done well to adapt more conservatively, because the advent of audio recording and the internet have removed the selection pressures that favoured writers over singers.2

Unfortunately, it didn’t, and those who wish to revive preliterate techniques must do so by a wilful act of atavism. This gives rise to a variant on the ‘evolutionary’ objection, according to which ancient forms of poetry are suited to ancient forms of society, and any attempt to restore them in the present day is tantamount to larping.3 This is like saying that no-one today should practice martial arts or grow vegetables, because we live in an over-pacified total state that feeds its population by mechanized agriculture. And this is no idle comparison, for in all three of these cases the deeper aim of the practice is to cultivate human virtues and basic self-sufficiency.

Admittedly, it is hard to avoid the surface appearance of larping. The tradition of singing poetry to the lyre died out around a thousand years ago in England (give or take a few centuries each way), and so the factual basis for our revivalism must be drawn from Anglo-Saxon and other medieval sources. Admittedly, these do not tell us much about the musical side of the poetry as opposed to the verses themselves, and no-one living today can say for sure what a performance by an Anglo-Saxon scop would have sounded like. All we can say for sure is that the verses were sung (Old English singan4), and that they were accompanied by a lyre (called ‘harp’, hearpe), which had at least six strings and may or may not have been tuned to a diatonic scale.5

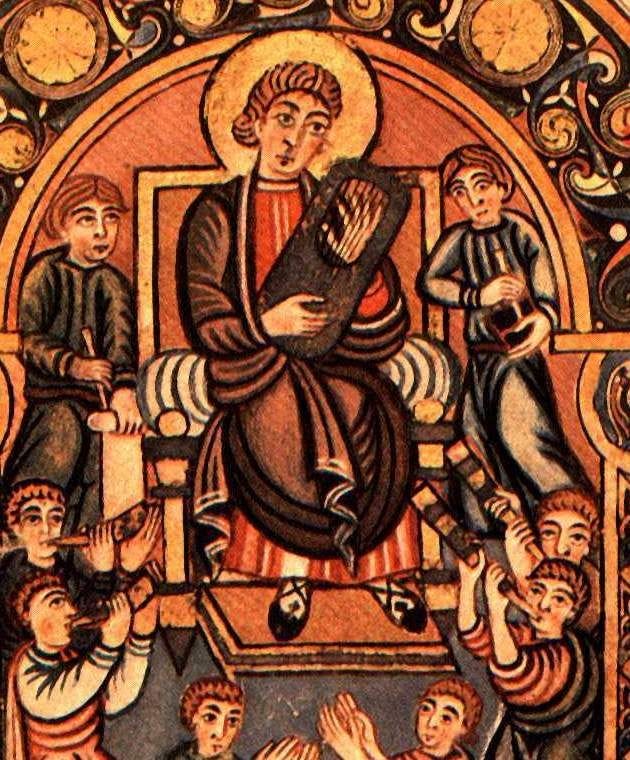

This illustration from the Vespasian Psalter may serve to represent the general idea of the scop singing poetry to the lyre:

Beyond these basics we can engage in various forms of guesswork on the basis of various clues, such as the metrical structure of Old English poetry, and the analogy with distantly-related South Slavic and Ancient Greek oral epic.

Utimately, however, none of what follows depends upon the accuracy of that guesswork. As I have said, our object is not to larp as barbarian bards in Germanic mead-halls, but to use historical examples as a starting-point towards the re-creation of a perennially viable art form. We need not reconstruct the Anglo-Saxon technique precisely in order to create our own, analogous technique. Yet by focusing on practicality, we may end up drawing closer to historicity as well.

Song and Strings Together

If the preliterate musical technique on which moderns are so ignorant can be compared to an environment swathed in darkness, then practical trial-and-error can be likened to the process of finding one’s way by touch. This is not the way of academic theorizing, which can be compared to reliance on sight, and hence finds itself helpless to proceed until new discoveries are brought to light. For example, after examining a wide range of factual material in his Ph.D. thesis ‘Anglo-Saxon Hearpan’, Christopher Page concludes with these words (p.331):

I have deliberately evaded the question of exactly how the collaboration between voice and instrument took place. That is an issue to be examined during the years ahead aided by practical experiment and collaboration between scholars in different disciplines. The problem is no more or less intractable than many others currently facing OE scholars, whose attempts at criticism can often be defeated by lack of information.

This was written more than forty years ago, and the academics of today seem no closer to reconstructing the technique of the scops. To my knowledge, the boldest leap in the dark by a scholar is still John C. Pope’s eighty-year-old book The Rhythm of Beowulf6, according to which the scop would have sung or chanted to a steady beat and struck the lyre at certain rests necessitated by the appearance of unstressed syllables at the beginning of verses.7

The first problem with this theory is that it reduces the instrument to a mere occasional supplement to the voice – hardly a worthy use for it, and hardly a usage accurately described by the words sang ond sweg samod ætgædere (“song and sound united together”, from Beowulf, line 1063). The second problem is that it assumes a niggling attention to positions of unstressed syllables that may well have never occurred to a scop, whose mind would more likely have been focused on the more regular occurence of stressed syllables.8 The third and biggest problem is that Pope did not as far as I know attempt to test his theory in performance.

Let us, then, turn instead to those who have taken up the lyre. The most famous of these is Benjamin Bagby, who has memorized the first thousand lines of Beowulf in Old English, and performs them to musical accompaniment in front of packed-out audiences. As you can see, he certainly looks the part:

Bagby’s whole performance, archived with video here, runs to over 90 minutes. Here we shall present only a short, representative audio snippet (see below for Old English transcription and translation):

Ða wæs on burgum Beowulf Scyldinga,

(Then Beowulf the Scylding bode in the town-forts,)

leof leodcyning longe þrage,

(people-king beloved, for a lengthy reign)

folcum gefræge. Fæder ellor hwearf,

(famed among the folk. His father had departed)

aldor of earde. Oþþæt him eft onwoc

(from this mortal earth. Now emerged an heir:)

heah Healfdene, heold þenden lifde,

(Halfdane the high, who held lifelong,)

gamol 7 guðreow, glæde Scyldingas.

(grey and war-grim, the glad Shieldings.)

Ðæm feower bearn, forðgerimed,

(A foursome of children, following in a row,)

in worold wocun, weoroda ræswan,

(emerged unto the world, commanders of armies,)

Heorogar and Hroðgar and Halga til.

(Heorogar and Hrothgar and Halga the good.)

Hyrde ic þæt Yrsa wæs Onelan cwen,

(Heard I that Yrsa was Onela’s queen,)

Heaðo-Scilfingas healsgebedda.

(bed-companion to the battling Swede.)

Þa wæs Hroðgare heresped gyfen,

(Then to Hrothgar was granted greatness in war,)

wiges weorðmynd, þæt him his winemagas

(martial fame, so that his friends and kinsmen)

georne hyrdon, oðþæt seo geogoð geweox

(willingly obeyed him; waxed his youths)

magodriht micel…

(into a mighty man-band….)

Although Bagby is by all accounts eminently qualified, and impressive in many ways, he takes some liberties here that must preclude our following at his heels. Take a second look at the Old English (or my translation, which is faithful to it), then listen once again to Bagby. Each line of the original poetry is metrical – two-phrased, four-stressed, and chymed (that is to say, stave-rhymed, or ‘alliterated’) according to strict and consistent rules. And this regularity of meter ought to tell us something about the way in which the poetry was originally performed. Yet Bagby sometimes sings the poem, sometimes speaks it, sometimes gabbles it, sometimes accompanies it on the lyre and sometimes doesn’t, sometimes hams it up with comic buffoonery (watch the whole performance; you’ll see what I mean), and generally does his utmost to ignore the meter and escape from its constraints.9

This is, perhaps, an inevitable consequence of his decision to perform in Old English – for who would want to listen for over an hour and a half to regular metrical intonation in a dead and unintelligible language? Yet for an audience able to follow the words and story, such regularity and repetition would be more tolerable, and would even help to focus attention upon the meaning of the song. We who wish to compose and sing in modern English can thus dispense with such forced variation.

But let’s stick with the Old English for the time being, while we look at another revivalist performance – this time by the more obscure William Rowan, a luthier and neopagan musician. Rowan’s performance of Deor deserves to be enjoyed in full, but once again we shall transcribe only a representative part:

Siteð sorgcearig sælum bidæled,

(He sits, sorrow-bound, severed from joy,)

on sefan sweorceð, sylfum þinceð

(with a murkened mind, musing to himself)

þæt sy endeleas earfoða dæl;

(that his share of hardship is surely endless;)

mæg þonne geþencan þæt geond þas woruld

(then he may bethink him that throughout this world)

witig Dryhten wendeþ geneahhe:

(wise God wends and turns:)

eorle monegum are gesceawað,

(honour he shows to jarls many,)

wislicne blæd; sumum weana dæl.

(certain glory; and to some gives woes.)

As you can hear, Rowan has simply set the words of the poem to a sung melody, to which he plays the lyre as an accompaniment. The aesthetic result is, in my judgement, wholly successful (and in the event that this man came back to Youtube and announced an album release I would snap it up in a handwhile).

What it does not constitute, in my view, is the invention of a generally viable technique. The ballad-like structure works only with the short stanzas and repeated refrain of this most ballad-like of Anglo-Saxon poems, and once again the metrical stresses are reduced to functional irrelevance. This in turn renders the ornamentation vestigial; note for example that the sudden dropping of chyme in mæg þonne geþencan / þæt geond þas woruld (by apparent scribal substitution of geond, throughout, for þurh, through) falls practically unnoticed upon our ears unless we are listening for it.

Let’s look at one more example. Peter Horn of Tha Engliscan Gesithas (The English Companions), an Anglo-Saxon culture society based in England, looks even more the part than Bagby:

There’s an explanation of the reasoning behind his short performance at the Gesithas website, from which we can gather that considerable thought went into it. Here it is:

Þær wæs sang ond sweg, samod ætgædere,

(There was song and strings, resounding together)

fore Healfdenes hildewisan;

(in front of Halfdane’s army-leader)

gomenwudu greted, gid oft wrecen.

(the gleewood struck for a story often told)

Đonne wit Scilling, sciran reorde

(Then I and Scilling, with a sheer voice,)

for uncrum sigedryhtne song ahofan,

(for our victory-lord lifted up a song,)

hlude bi hearpan…

(loudly to the harp…)

…scyl wæs hearpe,

(…the harp was sonorous,)

hlude hlynede, hleoþor dynede.

(Loudly it resounded, the sound was adin.)

Horn maintains a continuous accompaniment on the lyre and recites the verses over it, in a fairly plain intonation style that somewhat emphasises the metrical stresses. This, in contrast to Bagby, is at least sang ond sweg samod ætgædere (song and sound united together); whether it is what was meant by singan is more doubtful.

This, I think, is what most people would come up with when asked to imagine ‘alliterative poetry sung to musical accompaniment’. And it is more or less how I used to recite memorized Beowulf translations in my early days of experimentation on the lyre. What forced me to abandon this technique, and look for a more practical one, was my shift of focus from memorization to recomposition – that is to say, composition of verses on traditional models in the heat of performance – after reading Albert Lord’s Singer of Tales. The difficulty of verse recomposition is such that it demands maximum attention; a method that divides attention between the playing of a melody on the one hand, and the singing of verses on the other, is simply not going to work. (Indeed, this division of attention causes problems even with memorized recital, as evidenced by the one or two instances in which Horn appears to flub his verses).

A truly practical technique must bind song and strings together, so that playing and singing are united and do not entail division of attention. The simplest way to accomplish this is by matching the four stressed syllables of the sung metrical line to at least four corresponding lyre-strokes in the accompanying musical line. This results in a basic, stripped-down ‘backing tune’ to the verses, to which complexity could potentially be added by skilled singers and lyrists.10

I am no skilled singer or lyrist and so can only demonstrate the method in its maximum simplicity. To be consistent with the preceding examples, I shall do so with some verses of Beowulf in Old English, and confine myself to the block-and-strum technique shown on the Vespasian Psalter. The method may well seem the crudest of all, but you must bear with me here, and not disparage the eagle’s egg by comparison with the cockerel’s crest.

Hwæt we Gar-Dena in geardagum,

(Of spear-armed Danes in the days of yore,)

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon;

(Of kings of tribes, what clamour we’ve heard,)

Hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon;

(How the highbreds acted with valour;)

Oft Scyld Scefing, sceaþena þreatum,

(Often Shield Sheafing, midst shoals of enemies,)

monegum mægþum meodosetla ofteah,

(From many a nation the mead-seats wrested,)

egsode eorlas, syððan ærest wearð

(terrified the earls, since in his earliest days)

feasceaft funden – he þæs frofre gebad,

(as an abandoned foundling – then he found solace,)

weox under wolcnum, weorðmyndum þah…

(waxed beneath the sky, won worth and honour)

oðþæt him æghwylc þara ymbsittendra

(up until each of them, all his neighbours)

ofer hronrade, hyran scolde,

(over the whale-road, had to obey him)

gomban gyldan; þæt wæs god cyning…

(and gift him their gold; how great was that king…)

Whether a performance by a scop at the court of Hengest would have sounded anything like this is anyone’s guess11, but the method satisfies the basic practical requirement of binding the metrical and musical lines together.

Weaving The Lines To One

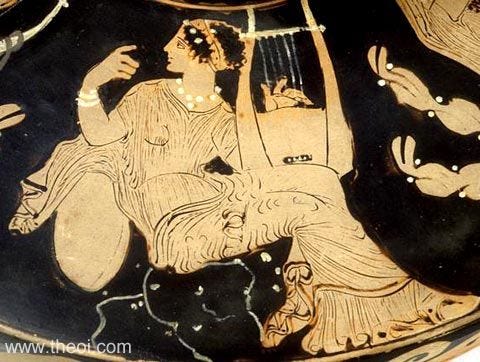

Let us now expand upon this rude germ of a technique. Now that we have figured out the method of matching musical beats to stressed syllables, we can depart from the modern academics and lyre-revivalists, and return to the surer guidance of the South Slavic poetic tradition; that is to say, to that distant cousin of the scop, the guslar:

This guidance must remain oblique and analogical, because the gusle is an alien instrument to the West and the style of singing associated with it is far from mellifluous to modern ears. Avdo Međedović, the greatest of the guslars recorded by Milman Parry in precommunist Jugoslavia, sounded like this12:

Avdo was famous for versification, not for singing or musical technique, and I can assure you that there better examples of gusle virtuosity in the audio files at the Parry Collection. But since the texts of the poems are presented without translations, without commentary, and often transcribed in slapdash handwriting, it can be very difficult to figure out how the music is being used to accompany the verses. The subject is barely touched upon in Lord’s Singer of Tales, and most subsequent books on oral theory neglect it altogether.13

Hence I have not yet found a more useful description of the guslars’ musical technique than George Herzog’s short article “The Music of Yugoslav Heroic Epic Folk Poetry”. Here’s the meat of it, garnished with some emphasis:

A Yugoslav heroic epic song has at least: (a) an introductory musical line, (b) one or more "lines of continuity," (c) one or more "dramatic lines," (d) a final line. The introductory musical line or idea may be repeated or spread over a few initial lines of the text, and it is used after every instrumental interlude which the singer inserts to furnish relief, and rest for himself, between larger subdivisions of the song. The musical content of the final line or lines is closely related to the introductory musical matter, or is actually a repetition of it. The "lines of continuity," so designated here because they carry the main burden of the continuity of the text, are musically less elaborate and less ornate. They are rendered in a rhythmic recitative which occasionally shifts to a more flexible, somewhat rubato rendition. The dramatic lines show more tonal variety and employ some tones higher than those of the continuity lines; these lines are used much more sparingly than the latter. With regard to melodic or tonal variety, ornamentation, rhythmic detail, or dramatic effect, there is a series then, descending in richness from the initial lines to the dramatic lines and then to the lines of continuity.

This musical material is accompanied by the unceasing playing of the gusle. The instrument begins with a short prelude. After the entry of the voice, the accompaniment follows the latter in a so-called heterophonic technique: the two voices together render somewhat divergent versions or forms of the same melodic line. The pause at the end of each sung line is filled out by the instrument with short stereotyped figures; the interludes and the postlude or coda (which is at times not represented) are also purely instrumental. Prelude, interludes, and postlude bring always related material and are often quite similar. While they and the brief line-final figures are rather ornate, the instrumental part becomes simpler when it accompanies the voice; it follows the latter rather closely so that the two voices are essentially in unison. Simultaneous intervals between the two, usually seconds, occur chiefly in text-final positions.

Boiled down to basics like this, the music of the guslars becomes much more intelligible, and applicable in principle to the lyre and other string instruments. Let us begin with the most important principle: the introduction of the song by an instrumental prelude-cum-interlude, which is then reduced down to a less complex ‘line of continuity’ in order to accompany the voice.

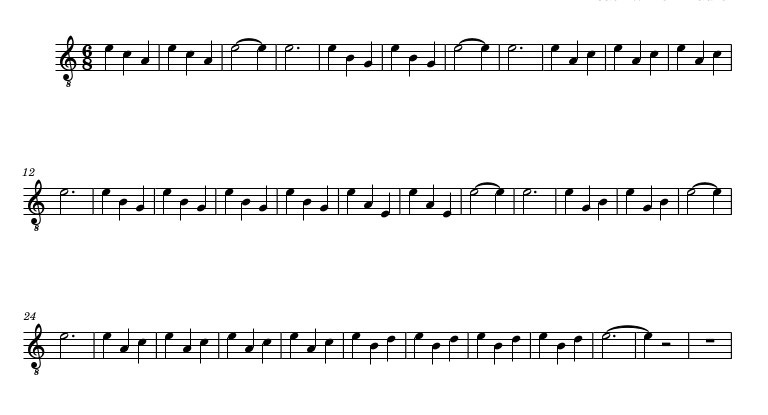

For purposes of demonstration, we shall use an easy little melody that I came up with in the first day or so after getting my hands on a lyre:

I was in two minds about including a written score here, and must clarify that it represents only one possible form of the melody, which is subject to variation and semi-improvization in practice (quite limited in my case, but there is no reason why such preludes should not become just as ornate as those described by Herzog). And it should go without saying that written scores have no place in actual performance.

Simple though it is, this melody must be further stripped down to a ‘backing track’ with four beats per measure once the dominant role in the song is assumed by the voice. This ‘line of continuity’, which I prefer to call a reduction, must preserve the recognizable essence of the melody so that it can flower back into the interlude form whenever the singer falls silent. This one can be reduced like so:

In the case of both the prelude-interlude and its reduction, the high E drone can be switched to a low one, and the melody inverted and played more forcefully in order to create ‘dramatic lines’ with a harder and more heroic feel. There are other variations that involve retuning, and some that involve moving the drone up and down (on lyres with more than seven strings; the one that I am using here has nine, though the one that I prefer to use for blocking and strumming has seven). In all variants the basic essence of the melody is preserved.

Just as has been demonstrated with block-and-strum chords, once the prelude-interlude has been switched to the reduction, each two strong stresses in each metrical half-line should be sung over each two lyre-strokes in each musical bar so that “song and strings are united together”. This is the technique proper, which we shall demonstrate by singing a few verses from The Nameless Isle by C.S. Lewis – one of the best works to come out of the modern alliterative revival, and a nautical mile better than anything in the Narnia books.

In this dreamlike story, a shipwrecked sailor is washed up on a mysterious island where he encounters several semi-allegorical characters. (Those interested in checking it out can find it in Lewis’s Narrative Poems, alongside three other poems written in rhyme.) Here I shall show only how the first few lines would be sung to the reduction just after the completion of the prelude-interlude.

In a spring season I sailed away,

Early at evening of an April night.

Master mariner of the men was I,

Eighteen in all. And every day

We had weather at will. White-topped the seas

Rolled, and the rigging rang like music

While fast and fair the unfettered wind

Followed. Sometimes fine-sprinkling rain

Over our ship scudding sparkled for a moment

And was gone in a glance; then gleaming white

Of cloud-castles was unclosed, and the blue

Of bottomless heav’n, over the blowing waves

Blessed us returning. Half blind with her speed,

Foamy-throated, into the flash and salt

Of the seas rising, our ship ran on

For ten days’ time. Then came a turn of luck…

Although I am reciting from the book here, which induces a certain monotony, it should be noticeable that the tempo of the reduction becomes somewhat irregular by modern standards once paired with the voice. In the event of recomposition, there would be more variation and semi-improvization: a metrical off-verse might be dropped and replaced with a melodic half-line, or a choice between a movement up or down the scale might be made on the basis of the narrative, or the verses might be broken up by mini-interludes of one or two lines in length. Variants of the melody and reduction might also be adopted mid-song for various narrative reasons.

I have not, of course, forgotten that recomposition was the whole rationale and selling point for this otherwise simple method. But that is a harder business, and a demonstration for another day; so for now, you shall just have to take my word for it that this technique is suitable for the oral poet who composes his verses in the heat of performance.14 Alternatively, you could take up the lyre and do some experimentation of your own…

Unqualified Qualifications

Here at Anamnesia, we are somewhat fixated on recovering the long-lost art of recompositional epic. But most people writing neo-formalist or traditionalist verse on Substack do not share this fixation, and tend towards shorter and more finessed lyric poems that are better memorized than recomposed. Can those uninterested in narrative poetry get anything out of the technique presented here?

The answer is that yes, of course they can. Simply memorize a lyric poem in chyming or accentual verse and sing it to a set of notes or chords on the lyre. Since we are dealing with shorter memorized poems, the backing tune can become more complex, or a melody can be played over a succession of chords simultaneously with the voice.

Another obvious point is that there is no essential need to use a lyre. The main advantage of this instrument lies in its simplicity. But it does not come cheap15, it has no cultural foothold among modern men, and one imagines that it would be supplanted by the acoustic guitar in the event that tradpoetry became more widespread. Or what about the electrically-amplified guitar? Or the piano or pillar-harp? Or more exotic instruments such as the lamellophone (mbira)? It would be interesting to experiment with any one of these, though some results would surely be more aesthetically-successful than others.

This may seem an absurd statement, since literary poetry was able to ‘effloresce’ for so many centuries. But it has always been fructified to some extent by the remnants of oral poetry (consider the influence of Homer on the Augustans, the English ballad tradition on the Romantics, even that of hip-hop on some elements of modpoetry); and more importantly, it has always retained trace elements of mnemonic and music, lost only at the dawn of the present era of ‘hyperliteracy’. (See, for example, this article on the much more musical verse-recital style of the Romantic era; the thought has crossed my mind that our modern preference for unvarnished spoken-word recital is a bit like our taste for the ghostly husks of uncoloured Greek and Roman statues.)

All cultural traditions must adapt to circumstantial pressures, but the point of tradition is to hand down (traditio), and anything other than conservative adaptation defeats the object. One example of ‘adaptive’ culture-destruction narrowly avoided would be the 20th-century movement to abolish traditional Chinese characters, largely on the grounds that they were too difficult for the proletariat to write, which has now lost all justification because texting and word processing has mostly supplanted handwriting in China.

This point of view typically goes hand in hand with a snooty dismissal of South Slavic oral epic (see e.g. Eric Havelock, Preface to Plato), which survived into the mid-twentieth century in an increasingly literate culture among very unheroic shepherds, farmers and shopkeepers, thus derailing the straight lines of development laid out in historicist theories.

For those of you who know some Old English: the Bosworth-Toller entry for this word gives a range of meanings that include mere recital and composition of poetry, but none of the cited examples seem inconsistent with the base meaning of ‘to sing’. Note the attribution of singing to birds (fugelas), a trumpet (byme), and rings of iron (hringiren) clanging on the mailshirts of warriors, as well as the juxtaposition of singan with secgan (to say). Of course it is quite plausible that singan might have extended to a kind of rhythmic chanting of verses, but this too may have been closer to song than the spoken-word style of recital used today.

This detail comes from the 9th-century musical treatise of Hucbald, which may be describing classical and not traditional Germanic practice.

In this article, Thomas Cable lays out a semi-musical theory of Old English versification, in which he claims that it may have been sung like Gregorian plainchant with varying pitch-accents linked to strong, weak and intermediate stress. He says very little about the lyre but seems to have envisaged its being used to replicate the improvized melody generated by the alternation of stresses. Page in his thesis (pp.248-69) also discusses various accent-marks found in Old English and Old Saxon religious-poetic texts, but most of them seem to bear no relation to stress, and I am not convinced that they represent anything more than guidelines for recital in a literary tradition far removed from the oral scop and his lyre. In any case, the use of stresses to generate tones is a non-starter for modern revivalists, since the resulting melodies would be too repetitious to be acceptable to modern audiences.

Robert Creed later put forward a heterodox version of the Popist theory in his ‘New Approach to the Rhythm of Beowulf’, showing (on p.11) a scansion of the first 25 lines of Beowulf with initial lyre-strokes marked as (/). I tried playing this on the lyre, but either failed to get it right, or else managed to get it right and did not like the result one bit. In any case I do not feel that the result is fit to be reproduced here.

Another common critique of Pope expressed here takes him to task for his use of isochronous time-measures, which did not exist in most premodern music. Page (pp.33-8) defends him on the grounds that all music is basically time-measured, and that the Popist theory does not depend upon the modern concept of isochronous measures.

In light of this self-explanatory article from Bagby, this judgement of mine might be a bit unfair. It would seem that he knows full well what he is doing, and is trying to mask the metrical structures to some extent in order to lessen the rhythmic repetitiousness. I suspect, however, that he underestimates the extent to which such repetitiousness would be tolerable to an audience able to understand the words and follow the story. It is certainly tolerated in the backing beats of rap songs, as well as in the backing tracks of role-playing videogames (such as this exceptionally repetitive one, and this one, which some repetition-enjoyer has seen fit to extend to three hours).

Now it should become clear why tradpoetry cannot be founded on iambic pentameter, despite its superficial resemblance to the South Slavic decasyllable and its prestigious association with literary epic. Most music in the Anglophone world is in 4/4 time, and this would seem to be instinctive or at least long-habituated to speakers of English, so the extra beat of the iambic pentameter line would inevitably make a nuisance of itself.

On reflection, this is a bit noncommittal, and since I took the trouble to demonstrate my technique in Old English I may as well make some sort of case for its historical verisimilitude. Certainly the singing style is modern (the medieval one may have sounded more like that of the South Slavic guslar, but would sound monotonous to modern ears), and the melody is a fixed one like those of the guslar, which I think is a safer bet than any attempt to reconstruct ex nihilo a method for improvizing the melody (Stefan Hagel has done this for Homeric lyre-singing, but the technique is based on the Ancient Greek pitch-accents, which did not as far as we know exist in Old English). The fifth-century testimony of Sidonius Apollinaris refers to the “thrumming” of barbarian plectrums (presumably on lyres or harps) that has driven away his Muse, and reference is made in Beowulf and Widsith to the ‘clear’ (sweotol) and ‘bright’ or ‘sheer’ (scir) voice of the scop, so I suspect that traditional Germanic singing involved forceful striking of strings and emphatic singing of words; to assume that the stressed syllables of the meter were those emphasised in song (with the unstressed ones subordinated so as not to interfere with the rhythm) is simply the path of least logical resistance, as is the assumption that the strings kept time with them. I do not intend to imply by my basic demonstration that the strings were only struck in time with the stressed syllables; one imagines that a scop playing his lyre after the fashion of the Vespasian Psalter illustration would have struck extra notes with his left hand as well (see this video for a rebuttal of the notion that such polyphony was invented in the Renaissance and did not exist in older forms of music.)

The short excerpt of Avdo’s singing comes from this video, which helpfully puts the Serbo-Croatian words and basic meanings upon the screen. Note that Avdo defers the final syllable of each line to the start of the next one, a trick that also works in English with my own technique, on condition that the final syllable in a given line is also its fourth metrical stress (e.g. as in “On a noontide in summer / when the sun was at its height”). I hope to demonstrate this method in later posts featuring song-poems.

It seems that the late John Miles Foley corrected this problem by setting up a website devoted to analysing one of the Parry Collection songs, but it has vanished from the web and its archived page lacks the audio file. Any directions as to where this may be found today would be much appreciated.

Truth be told, my quest to recover the art of recomposition is far from complete, though I hope to post some demonstrations in the next few months. But what doubts I have had about the tools in my hands relate almost entirely to the meter; the musical technique shown here succeeds in eliminating distraction of attention by uniting the lyre and the voice.

Germanic lyres can be found on Etsy, but these are hand-made and thus not cheap, and top-of-the-range Luthieros ones are even more expensive. The mass-produced models that can be found on Amazon are fine for practice, and to a certain extent for recording, since we are using quite a simple musical technique in which the focus is on the verses. Be sure to get the Chinese ones, not the more ‘trad’-looking and lower-quality Pakistani ones.

notwithstanding my deep appreciation for the work that has gone into this research, as a practicing poet i have reached a far different conclusion vis-à-vis performing alliterative verse. i think a drum should be used instead, & its beats to occupy the 𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑡𝑠 instead of the half-lines. (one heavy beat before, & two quick beats between.) it puts too much on the audience to discern words that are already unfamiliar, over contrasting sounds. likewise we are too accustomed to listen to stringed instruments for melodies instead of for rhythms, & find much of our enjoyment in syncopation. (syncopation in allliterative verse comes from varying many syllables or few to a single half-line, but not varying the beat.) --still, all should be tried. the important thing is to make poetry in which the sound counts.