Anglo-Saxon Rhythms

The modern revival of the oldest English verse-style

There are a number of barriers to the restoration of traditional poetry in modern English. By far the most daunting one is the fact that we Anglos – unlike the ancient Greeks and the modern South Slavs – no longer possess a traditional poetic language with formulas and phrase-patterns for all occasions. Although some of these might be recovered from translations or gleaned from literary poetry, the greater part of rebuilding could only ever be a work for many hands and much time.1

But no such work can be begun without the prior solution of a more fundamental problem. In ancient Greece and recent Jugoslavia, epic poetry was always sung to a common poetic meter (although others existed for other genres) – among the Hellenes this was the hexameter, among the South Slavs the decasyllable. This adherence to one meter served to ‘hold together’ the formulas, phrase-patterns, and other verbal features of traditional poetry, much as the bricks of a house are held together by cement. Such an element is nowhere to be found in modern English poetry, in which there is no agreement even on the use of meter.

It should go without saying that ‘free verse’, which has no more rhythmic and mnemonic virtue than prose, is therefore no more fit for traditional-poetic purposes than mud is fit to hold bricks together. Does that mean, then, that we should join the formalists in their project of retvrning to rhyme? If we want a common meter that can survive in oral tradition, that of the ballad tradition is surely not to be sniffed at.

Alas, things are not so simple. The ballad tradition dealt mainly in short songs, and was memorial in nature – that is to say, the singer memorized and recited, an art for which rhyme is perhaps best fitted. Traditional poetry in the Greek or South Slavic sense involves longer narratives, and the art of recomposition – the telling out of verses in the moment of performance on the basis of traditional models. End-rhyme in English is too troublesome to be extemporized in this way2; it produces a jaunty tone that is better-suited to satire than epic (just look at Wackerbarth’s Beowulf); and its requirement of constant forethought for the end of the line is ill-suited to the ‘adding style’ described by Milman Parry, by which the oral poet stacks compact phrases end to end like so many building blocks.

Perhaps, then, we should be retvrning instead to unrhymed iambic pentameter. At first glance, this seems ideal – it is less artificial than rhyme, it resembles the South Slavic decasyllable, and it is associated with the prestige of Shakespeare, Milton and Wordsworth. Yet this is in origin a literary meter, and one that introduced into English the foreign element of syllable-counting, producing a somewhat unnatural cadence of speech that trips better off the page than off the tongue. Moreover, the literary greats who used it were not traditional poets by our definition, and a meter that evokes them at every turn would be in some sense at odds with the restorationist project.3

To find a meter that is not only practical, but also charged with the right sort of associations, we must depart the beaten path and risk a more eccentric movement. Only in the relegation league of verse-styles do we happen upon the oldest meter in English – what is usually called ‘alliterative verse’. Perhaps this was the meter of our lost oral tradition, or perhaps not, but in any case it is closer to it than anything else that has been preserved in writing.

This was the common meter among the Anglo-Saxons, and survived into the High Middle Ages4, but died around the sixteenth century. It was then revived after centuries of disuse in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, by antiquarians like Francis Gummere, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, and had some early influence on modernist poets5 but found little long-term acceptance. Since then it has enjoyed a quiet revival in fantasy writing, which has long been tracked by Paul Deane at his website Forgotten Ground Regained.

We might venture to say that the restoration of traditional poetry will lack all authority unless it be based upon this verse-style (or some derivative thereof), just as a fallen dynasty cannot be restored but by a prince of the blood.

But this style eludes all those who approach it in a careless spirit, so let us take the time to learn its rules. I shall begin with a representative sample: a translation of an Old English hymn, composed by a cowherd named Cædmon, who reportedly learned the art of verse with the help of divine inspiration.

Now we must hail Heavendom’s Guardian,

The might of the Architect and his mind-thoughts;

The Glory-Father’s workings; as to wonders all

The Everlasting Ruler wrought a beginning.

First he created, for earth’s children,

Heaven as a roof – the Holy Maker –

Then the middle-earth, humanity’s Guardian,

The Everlasting Ruler, afterwards fashioned:

Land for the living – the Lord Almighty.

Hopefully, if you read these lines attentively (or better, aloud), you should have noticed some features that characterize this style.

First, the number of syllables in each line is somewhat less than consistent:

The might of the Architect and his mind-thoughts (11)

First he created for earth’s children (9)

Land for the living – the Lord Almighty (10)

This is because the meter is not based on a count of total syllables, but on a beat of four stressed syllables per line, variously surrounded by weaker syllables – e.g. LAND for the LIVing, the LORD alMIGHTy.6 This is more natural to the stress-timing of English, as long as we read with a normal speech accent and avoid the artificial cadence of iambic pentameter. Note that the clashing of stressed syllables, avoided like the plague in other styles, is quite permissible in this one – e.g. the MIGHT of the ARchitect and his MIND-THOUGHTS.

Second, there is no use of end-rhyme, but the style is structured around a different form of ornamentation that works by matching the initial sounds in stressed syllables:

(N)ow we must (H)ail (H)eavendom’s (G)uardian

(F)irst he cre(A)ted for (E)arth’s (CH)ildren

Then the (M)iddle-(E)arth, hu(M)anity’s (G)uardian

(L)and for the (L)iving – the (L)ord Al(M)ighty

This is commonly termed ‘alliteration’, hence the moniker ‘alliterative verse’, but in my view this word is misleading. In truth, this is a form of rhyming verse (based on what is called head-rhyme or stave-rhyme), but to refer to it as such would risk confusing the reader. So we shall coin the unique term chyme7 in place of ‘alliteration’, and may hereafter refer to the meter as chyming verse.

The examples above show why this change of terminology is needed. The word humanity alliterates on the letter h, but is stressed on the sound of m – thus it chymes with the world middle. In the same way, the word created alliterates on c but is stressed on a, and chymes with the word earth (because all vowels chyme with each other). Stressed sounds count, initial letters are irrelevant – thus deceased chymes not with dead, nor with decayed, but with sorrow and desist and psalm (and so on).

Third, there is a traditional rule for placement of chyme, which I shall try to express as succintly as possible: either the first or second stress (or both) in each line must chyme with the third stress, but the fourth stress must not chyme with the third. This allows for a range of legitimate patterns:

The Everlasting Ruler wrought a beginning (ABBC)

Heaven as a roof – the Holy Maker – (ABAC)

Land for the living – the Lord Almighty (AAAB)

The fourth stress is thus deliberately omitted from the chyme scheme, and is only brought back into it in the patterns ABBA (e.g. “The Everlasting Ruler wrought an end”) and ABAB (e.g. “Heaven as a roof, the Holy Ruler”). The pattern AAAA (e.g. “Land for the living, the Lord of Love”) is considered to be overegging the pudding, but it does sometimes rear its head in Middle English texts.8

As you can imagine, this rule can lead to inversions of normal word order (as in “to wonders all”). While this is a legitimate feature of poetic language, it is harder to pull off in our modern non-inflectional English, which has led some (notably Paul Deane) to propose the abolition of the rule. For now, we will hold onto it, on the grounds that one should first understand a rule before considering whether to break it.

Last but not least, we note the ‘adding style’, which shows the kinship of this meter with oral tradition. Each line is constructed from the building-blocks of two half-lines, each consisting of a phrase containing two strong stresses. This is easier to notice when the mid-line caesuras are marked:

The Everlasting Ruler / wrought a beginning

First he created / for earth’s children

These phrases must be basically self-sufficient in meaning – so we cannot have lines like “He wrought the Everlasting / earth a beginning”, or “First for earth’s / offspring he made”, the component halves of which would crumble into unintelligibility were the lines to be snapped in two. The fact that even the best literary poets often forget this rule shows their distance from the mentality of the oral poet.

This much will do for a brief introduction to the meter. I hasten to say that I have left much unsaid, and that those who want more detail and depth are strongly advised to check out Paul Deane’s ‘Field Guide to Alliterative Verse’.

Let us rather show than tell, by taking a look at some more verses written in this style, this time from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lays of Beleriand. This book contains two narrative poems, one about Turin Turambar and the other of Beren and Luthien, and the following section depicts the telling of the latter’s story to the former. (I have added some bold letters and slashes to highlight the chymes and caesuras).

There was told to Túrin / that tale by Halog

that in the Lay of Leithian, / Release from Bonds,

in linkèd words / has long been woven,

of Beren Ermabwed, / the boldhearted;

how Lúthien the lissom / he loved of yore

in the enchanted forest / chained with wonder –

Tinúviel he named her, / than nightingale

more sweet her voice, / as veiled in soft

and wavering wisps / of woven dusk

shot with starlight, / with shining eyes

she danced like dreams / of drifting sheen,

pale-twinkling pearls / in pools of darkness;

how for love of Lúthien / he left the woods

on that quest perilous / men quail to tell,

thrust by Thingol / o'er the thirst and terror

of the Lands of Mourning; / of Lúthien's tresses,

and Melian's magic, / and the marvellous deeds

that after happened / in Angband's halls...

And some more, this time from C.S. Lewis’s poem The Nameless Isle, which in my view is superior to Tolkien’s work (chyming verse being the only literary field in which this could be said). The story is something of a spiritual allegory – narrated by a shipwrecked sailor, who washes up on a mysterious island, and meets a witch who turns men to beasts and later a wizard who turns them to stone.

There were trees taller / than the topmost spire

Of some brave minster, / a bishop’s seat;

Their very roots / so vast that in

Their mossy caves / a man could hide

Under their gnarl’d windings. / And nearer hand

Ferns fathoms high. / Flowers tall like trees,

trees bright like flowers: / trouble it is to me

to remember much / of that mixed sweetness

the smell and the sight / and the swaying plumes

green and growing, / all the gross riches,

waste fecundity / of a wanton earth,

– gentle is the genius / of that juicy wood, –

insatiable the soil. / There stood, breast high,

in flowery foam, / under the flame of moon,

one not far off, / nobly fashioned.

Her beauty burned / in my blood, that, as a fool,

falling before her / at her feet I prayed,

dreaming of druery, / and with many a dear craving

wooed the woman / under the wild forest.

She laughed when I told / my love-business,

witch-hearted queen. / 'A worthy thing,

traveller, truly, / my troth to plight

with the sea villain / who smells of tar

horny-handed, / and hairy-cheeked.'

Then I rose wrathfully; / would have ravished the witch

in her empty isle, / under that orb'd splendour.

Now – I must confess that I have chosen these excerpts not only to show off the possibilities of this meter, but to show up some of the flaws that shall have to be smoothed away if it is to be restored to its former glory. Did you catch a couple of awkward lines in the Tolkien and Lewis verses? Let’s look at them in isolation:

Thrust by Thingol / o'er the thirst and terror (Tolkien)

Gentle is the genius / of that juicy wood (Lewis)

The repetition of words stressed on [θ] and [dʒ], and also [ʃ] and [tʃ], creates an unfortunate effect in modern English. These words are also relatively scarce, and tend to lead to the sort of forced diction that has led modernists to sneer at the use of rhyming meters.9 Most importantly, they are bound to hang like leaden feathers on the winged words of recomposition.

Evidently what we need is a system of loose chyme, analogous to the loose rhyme that has eased the flow of verses in freestyle rap. The medieval masters did not disdain to take such wise liberties. Here are some examples from Beowulf (translated primarily to convey the sound changes):

Hwæt we Gar-Dena / in geardagum (O10 of gore-speared Danes / in yoretide days)

And þa cearwylmas / colran wurðaþ (And the wellings-up of care / chill and wane11)

As you can imagine, Old English poets had fewer chymes to worry about, because some sounds that had diverged in pronunciation were treated as equivalent and written with the same letters. As time went on, these diverged more clearly, but poets composing in the old meter continued to take the liberty of equating certain sounds. Thus, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight we see h-sounds chymed with vowels:

Hit was Ennias the aþel / and his highe kynde (It was Enneas12 the noble / and his highborn kin)

And, in the Alliterative Morte Arthure, the equation of w- and v-sounds:

In this wretched world, through virtuous living

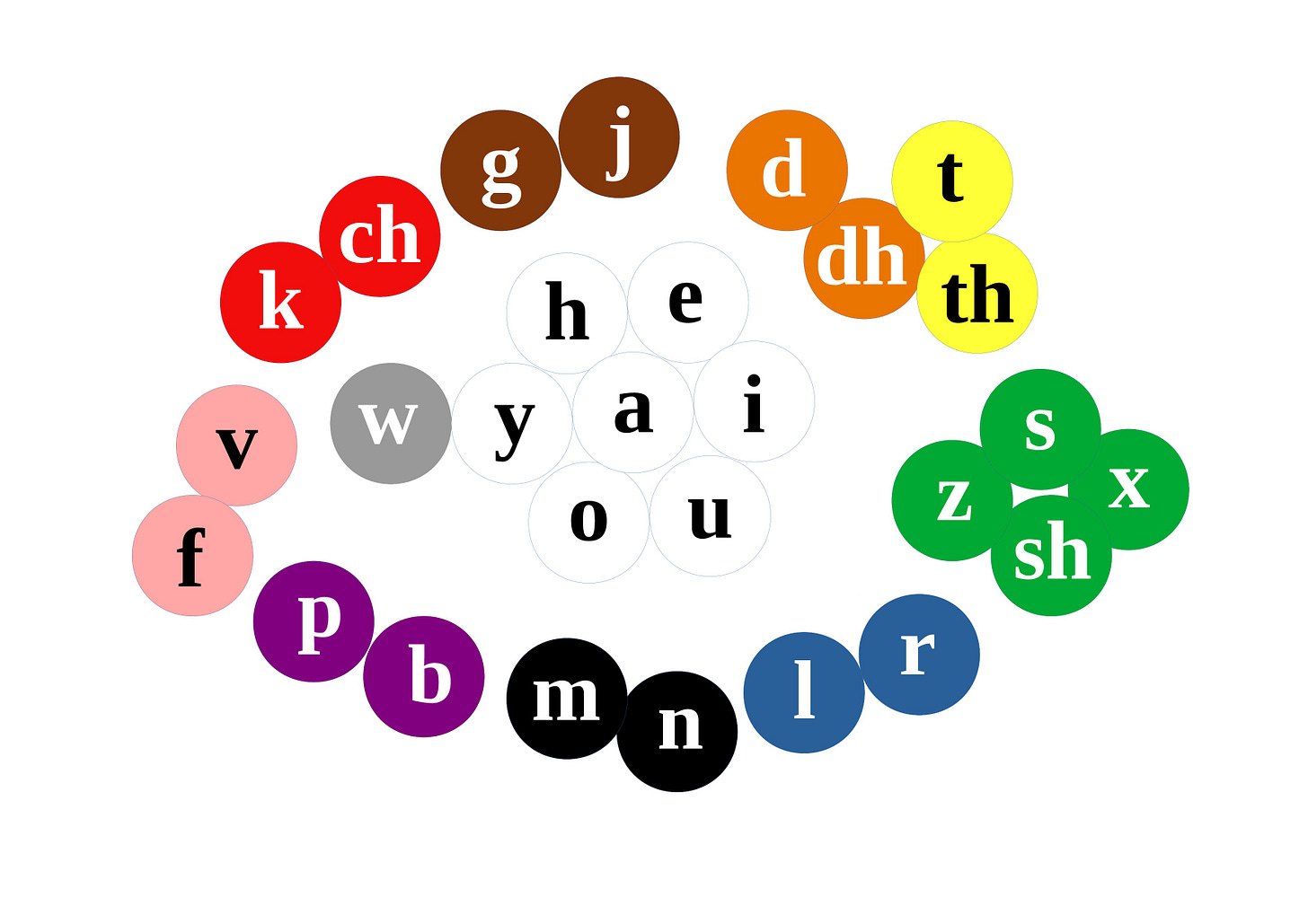

We should not of course copy these sound-equations exactly, because some of them reflect very different norms of pronunciation. We must come up with our own, modern system of loose chyme, geared to our own problems and suitable for our own conventions of sound-association. Here is a visual representation of one possible system, biased towards maximum simplicity:

Doubtless some of these equations are more controversial than others, and the practicing poet can take or leave them. (In particular, the three located at the bottom of the chart are less essential, and partly represent an effort at overall balance.) It is also worth remembering that any reduction in the number of chymes makes it harder to vary the fourth stress; but this is an advantageous trade, as it is almost always easier to find a variant for this stress than a chyme for the third one.

Such flexibility has its advantages, not just for experiments in oral composition, but for the faithful poetic translation of texts. In the following lines, which ‘translate’13 part of a scene from the first book of the Iliad in which Achilles insults Agamemnon, I have used bold text to highlight every instance of resort to loose chyme.

Though his hand was stayed, yet stopping not his anger;

Pelides14 spoke out with scathing words:

"You stout sack of wine, with the shifty eye

and aspect of a dog! And the heart of a deer!

Never have I known you, when the men take arms,

to arm yourself for battle; or an ambush dare

with the doughtest of Achaians; the din of warfare

cows you in your heart – like the call of death.

Better by far for you to prowl the width

of the camp of the Achaians, and chattels take

from he that sets his face at you, and speaks against you,

People-eating king! You prey on nonentities,

for otherwise, Atrides15, they themselves

would end your outrages – here and now..."

Loose chyme does not exactly make chyming verse easy, but it lessens the chance of getting stuck on anything truly insurmountable.

This much will do, I suppose, for an introduction to the old meter and my own thoughts on how best to adapt it to modern English. Yet there is a lot that we have left unsaid. We have made no serious attempt to probe the mystery of whether this meter was that of the original Anglo-Saxon oral tradition, or that of a memorial tradition associated with it, or that of a literary tradition derived from it. Nor have we yet provided experimental results proving that it is possible to practice recomposition in a poetic language based on this meter.

All of this will be treated in due time. For now, let us say only that chyming verse is about as close as English literary poetry comes to recompositional oral tradition. What lies in the darkness beyond might be a little more obscure, or a lot; but either way, the reclamation of this outpost on the frontier is an obvious place to start.

Here we might draw a modern analogy with internet memes. These may start their lives as works of individual art, but it is only constant reuse that preserves them as items of collective signification. We might say, with a faint echo of Parry, that one man could never have begun to put together the huge stock of memes that permeate the internet today.

This may seem unambitious when freestyle rappers manage to improvize verses in rhyme. But they have achieved this only by subordinating everything else to the rhyme-scheme, producing a kind of oral poetry that is better suited to stream-of-consciousness rambling than stable narrative. This video shows the improvization of a narrative by rappers, but it seems much more driven by rhyme-associations than ideas, and peters out after a minute or so into the usual rap conventions of flyting and self-eulogy.

There is another point on which to disqualify iambic pentameter, but it shall have to wait until we come to treat the subject of musical accompaniment.

I do not believe in the supposed death and revival of the meter between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, which strikes me as a scholarly mirage generated by a hundred-year gap in documentation at a time when the English language was that of a subjected people. To draw an analogy, a decade-long gap in a dead man’s diary is no basis for suggesting that he spent those years inactive or in a coma. It would, however, be interesting – given the differences between Anglo-Saxon and Middle English forms of the meter – to speculate on the degree of variation that might have characterized the underlying oral tradition.

Those who would like to know more are invited to check out Rahul Gupta’s PhD. thesis, which investigates the influences of this meter on Kipling, Pound and Tolkien.

Confusingly, some of these stresses can be doubled up, especially in later versions of the meter; and one can find all sorts of consistencies in the placing of unstressed syllables with the help of statistical modelling, which has led some academics to turn the stick and claim that it is after all the total syllable-count that matters. When we come to set this verse-style to music and song, we shall hopefully see how little all of this counts in the conscious mind of the poet, who must indeed think in terms of four stressed syllables per line.

I take this word (with a minor amendment in spelling, to stress the analogy with rhyme) from the eighteenth-century bibliographer Humphrey Wanley, who wrote that the poet of the Stanzaic Morte Arthure “useth many Saxon or obsolete words, and very often delighted himself…in the Chime of words beginning with the same letter”.

In my view, the overuse of thrice-chyming lines (AAAB, e.g. “Land for the living, the Lord Almighty”) in longer poems creates a similar bombastic excess, while also overly constraining the available diction for the second half of the line. But this stylistic habit is very common among chyming-verse poets, who have learned it from their medieval exemplars. It is somewhat more common in the Middle English texts than the Anglo-Saxon ones, and my suspicion is that it represents an ‘overcorrection’ made possible by writing.

This problem may never have existed in Old English. On the basis of my own sampling of the Beowulf text, I count fifteen distinct chymes in early Anglo-Saxon verse (not counting combinations like st- , sm- or sp-, nor rare sounds like p- that are nowhere found in stress-positions). In Tolkien and Lewis, again excluding combinations, I count twenty-two. Consider also that Old English had a much wider range of synonyms and kennings for basic terms (such as ‘man’, ‘king’, ‘sword’, ‘horse’, etc.)

It is more usual to translate the word hwæt as “lo!”, “attend!”, “listen!”, or something else meant rather to be shouted than said; but if this word were intended to be stressed, as is unavoidable when we shout it, then it would presumably be treated as a metrical stress in the line that it begins. Imagine a future civilization digging up transcripts of rap songs from the American imperial era, and trying to replicate the authentic sound of them, and beginning each of them with something like “YO!”, “WHAT UP!”, or “A’IGHT!”

The sounds in the original line are reversed in the translation: it is cearwylmas that is pronounced with a soft initial [tʃ] and colran that begins with a hard [k].

That is, Aeneas.

I put this word in scare quotes because I do not know nearly enough ancient Greek to translate any poem written in it. This experiment began as a mere conveyance of the first book of the Iliad into chyming verse by adaptation of English translations; but once I realised that none of them can really be trusted, I ended up making painstaking reference to every line and word of the original text.

Son of Peleus, i.e. Achilles.

Son of Atreus, i.e. Agamemnon.

I would wonder about preferring to group some vowels in chyming; my guess is one would rely on the ear.

What is the rule by which you determine if you're rhyming (chyming) the vowel or consonant?

i.e.

"running fast / the rain had past" vs

"running past / the sun was pale" seem like they could go either way.

I was not aware of the alliterative rules and requirements for this kind of verse when I wrote this poem in saxon meter; now I'm thinking I might want to rewrite it to "chyme." https://chieflylyrical.substack.com/p/november-evening-23-observing-the