An Alliterative Iliad (II)

The frank speech of Calchas the soothsayer

In the first installment of this work (preceded by all necessary disclaimers and explanations, which I’ll not repeat here), we witnessed the wasting of the Greek army by the plague-arrows of Apollo. In order to find a way to lift the curse, Achilles calls a meeting of the Greek commanders, in which Agamemnon is blamed for having offending the god by refusing to give his war-concubine Chryseis back to her father. Agamemnon’s unwillingness to part with the girl (at least unless compensated at someone else’s expense) will lead to a bitter dispute with Achilles, causing him to sit out the war and setting in motion the main events of the poem.

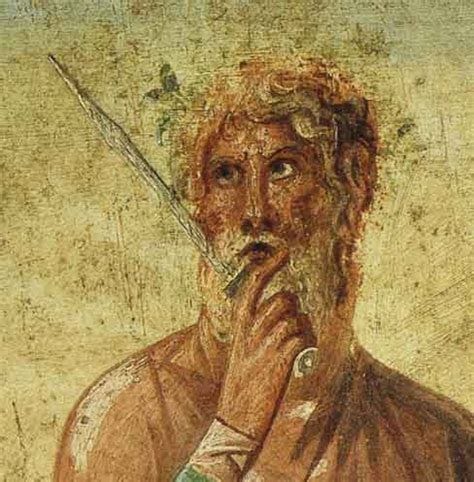

The indictment of Agamemnon is made by one Calchas, who seeks the kingly protection of Achilles before daring to speak up against the overlord of the host. Calchas is a mantis, or practitioner of divination – specifically the art of augury by which future events are divined by the flight and behaviour of birds. He was also able to predict the future by examining entrails, an art known as haruspicy. These practices were important to the Romans as well as the Greeks, as can be divined from the fact that our own terms for them come from Latin.

And what price, according to Calchas, must Agamemnon pay for his transgression? As we shall see, he must release Chryseis as a free gift to her father, along with a sacrifice of a hundred oxen (a hecatomb). So Agamemnon loses honour, owing not only to the loss of his war-prize (partly valued as a symbol of honour won in battle) but also to his forgoing the splendid ransom initially offered for the girl.

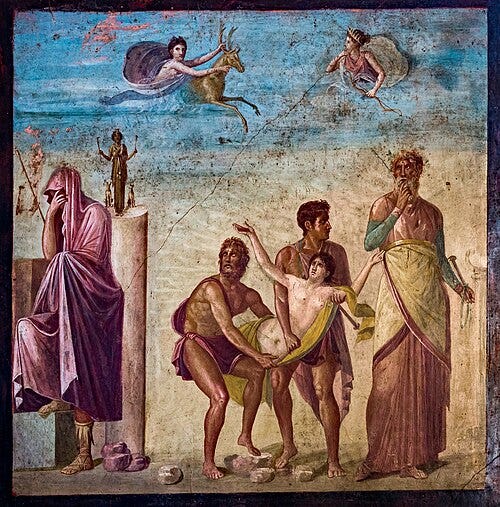

Although Agamemnon is generally portrayed as arrogant and selfish in the Iliad, he had good reason to become exasperated at the words of Calchas and to blame him for always being the bearer of bad news. Prior to the events of the poem, when Agamemnon had offended the goddess Artemis by killing one of her stags at the hunt, it was Calchas who instructed him to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia in order to appease the divine wrath and allow the Greek ships to reach Troy. For him to refuse to sacrifice one of his own family, while asking so many others to die in his brother’s cause, would not have been the ‘done thing’. In the famous painting of this scene by Timanthes, Agamemnon is shown with face veiled because the master painter did not know how to portray his grief.

So they gathered in council, together assembling, And swift-foot Achilles stood to spéak amóng them: "It seems now, Atrides, if we scape with life "From the war and the pestilence that wastes our host, "We must go pell-melling homeward, repelled and routed, "In defeat, from this fight! But let's first consult "Some prophet, or a priest, or a prober of dreams – "For dreams are from Zeus – for to show what cause "Has so incensed the archer-god: what act or fault? "Let altars smoke! Let hecatombs be paid – "So that for vows we may have broken he may blame us not, "And thus soothed by the smouldering of spotless lambs "And blemishless goats, his bane may lift from us." He spake, and sat; and the son of Thestor, Calchas the augur – who all things knew Of what was, and what is, and what will be after – Who was best among bird-seers, blessed by Apollo As a soothsaying oracle – whose arts had guided The ships of the Achaeans to the shores of Troy – This sage stood up now, and spake goodwilling: "God-loved Achilles! I would gladly tell you "What has caused the choler of the king Apollo "Who shoots from on high. But I will say it only "If you swear me a pact – that with speech and hand, "With word and with deed, you will do me aid – "Defend me with your might. Unless I miss my guess, "The ruler of Argives, who reigns supreme – "He who sways this host – will be incensed to hear it. "And woe to the underling who angers a king! "Today he might bite back the bile in his chest, "But his vengefulness will fester and be vented in time. "So tell me for truth: will you protect my life?" Fleet-foot Achilles fitly answered: "Take courage, Calchas, declare what prophecy "You learned from the god – beloved of his father, "Far-shot Apollo – whom in prayers you seek, "And discover knowledge, for Danaeans' sake, "Of divine foresight. In this force of troops "No man shall be so bold, while I breathe the air "And look on the daylight, to lay upon you "A heavy hand at the hollow ships – "Not even if you name Ágamémnon, "Who boasts himself above us as the best of the Greeks." And so blamelessly the seer, emboldened, spake: "'Tis nor for vow nor for hecatomb he harries us so, "Oppressing us with pains; but his priest was wronged "When Agamémnon dishonoured him – his maiden's ransom "Scorning to accept, and not setting her free; "For the sake of this affront, the afar-shooter "Afflicts us with his arrows; and no end will come "To the murrain of our host; he'll withhold no shames, "'Til unpurchased and unransomed – with no price exacted – "The bright-eyed girl goes back to her father, "And a blessed hecatomb bleeds in Chrysa. "Thus might we be pardoned, and appease the god."

So he spake, and sat; and the son of Atreus Arose, heroic wide-rúling Agamemnon – Baleful black wrath overboiled his heart, And his eyes were like embers, hotly blazing. Ill-stáring at Calchas, he bespake him thus: "Oracle of evils! Not e'er has come "Any good for me from your grievous tongue; "Ill-tidings are your joy; and tidings glad "From your words and works have never ónce come forth. "Divining midst Danaeans, you announce to all "That the far-shooting one afflicts us so "For the sake of his priest; for that the splendid ransom "For Chryseis the virgin I refused to trade. "Much did I prefer the maid to have "And hold within my house; for in every way "She more charms me than my wed wife, Clýtemnéstra; "In no wise is she worse: in her woman's form, "In her mind, in her works – a matchless girl! "Yet I'll loose her regardless – for I'm loath to watch "My people go on perishing in pyre-smoulders – "But see to it at once that a reward is found, "For to make amends to me. Unmeet 'twould be "If it were I alone in the Argive troop "Who should want an honour-prize; as all ye witness, "The prize that was mine own now elsewhere wends."

Notes

Although the original text was and is all Greek to me (see the first post), I gave some thought to the question of how best to render certain words and phrases in English. The reasoning behind these choices is explained below.

O God-loved Achilles…

Wherever the capitalized word ‘God’ is used here, the reference is to Zeus in his capacity as the highest Olympian god. The original term Διῒ φίλε (Dii phile) means ‘Zeus-beloved’, but the form of the word naturally evokes the Latin Deus (which is in fact a closer relation to it than Greek θεός theos, generic ‘god’ or monotheistic ‘God’).

We must go pell-melling homeward, repelled and routed…

‘Pell-melling’ and ‘repelled’ are intended to reproduce something of the effect of πᾰλῐμπλᾰ́ζομαι palimplazomai, ‘to be driven back in wandering confusion’, the p and l sounds of which seem to suggest the plashing sea over which the Greeks would have to return home (and on which Odysseus will wander in confusion for ten years after the conclusion of the war). A more literal translations might be ‘routed and set roaming’, or ‘wherved round to wander back’ (see here for the definition of wherve).

The bright-eyed girl goes back to her father…

The word in the original is ἑλικώπις (helikopis), a common epithet for a beautiful young girl, which literally refers to eyes that ‘turn’ or ‘roll’. The fact that helix ‘spiral’ is also a component of the word helicopter (the other is pteron, ‘wing’) is apt to stir the modern mind to a somewhat comical image. But we can interpret the idiomatic meaning of ‘spiralling-eyed’ as ‘swift-eyed’ or ‘quick-eyed’ (signifying the eyes of a bright and lively girl who is always glancing around), or perhaps ‘rolling-eyed’, assuming that the act of rolling one’s eyes upward (which I have seen a little girl produce with no obvious outside influence, and not in the culturally-accepted context of exasperation) was considered typically or charmingly feminine.

Most older translators read the word instead as ‘black-eyed’, but this would seem to be a much less useful traditional epithet and the interpretation has fallen out of favour.

The son of Atreus arose, heroic wide-ruling Agamemnon

The line in the original is ἥρως Ἀτρεΐδης εὐρὺ κρείων Ἀγαμέμνων (crudely transliterated, heros Atreides euru kreion Agamemnon), which as we can see contains the Greek ancestor of the English word hero.

The modern concept of heroism, even where not traduced by improper extension to the commonplace, refers to an essentially self-sacrificing masculine virtue such as that of a dutiful conscript soldier. But the ancient Greek concept was about greatness, not necessarily goodness, and strictly speaking was limited to mythical demigods and individuals whose magnificent achievements entitled them to cultic worship after their deaths. Assuming that the use of heros here is not solely metri causa (i.e. for the sake of meter, as per the theory of Milman Parry), one would think that it is intended to emphasise the mighty stature of Agamemnon as he rises to castigate the soothsayer.

In her woman’s form, in her mind, in her works

Agamemnon praises four qualities of Chryseis: her frame, her stature, her mind, and her works. ‘Woman’s form’ (not necessarily to be taken in a narrowly sexual sense) is arguably an unwarranted interpretation of the first two; it is partly metri causa and partly a case of listening for the dog that didn’t bark.

Brilliant how the alliterative constraints force creative solutions that actually preserve meaning better than literal translation. The "bright-eyed" rendering of helikopis captures that lively, darting quality way better than "black-eyed" ever could, especially when the original helix root suggests movement not just color. Worked on some Old English poetry last year and remmeber that epithets in Germanic verse often did similar work, compressing character into rhythmic formula without sounding formulaic.

Fitzgerald translated ἑλικώπις as 'the girl who turns the eyes of men' which is perhaps not literarlly accurate but it's a neat solution nonetheless. Great translation. I'm looking forward for further installments.