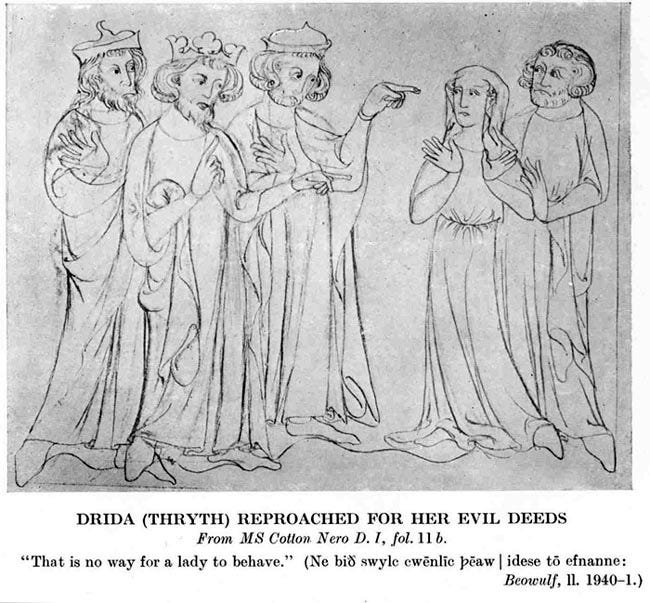

Rethinking Thryth (I)

A second look at the dark princess of Beowulf

In previous posts on the translation of Beowulf, we’ve explored some of the cruces (disputed words and passages) and mysteries of the poem1, seeking to revise older assumption without admitting worse distortion from modern ones. The crux addressed in this post is among the tougher ones, and my take on it is that earlier scholars got it more or less right before later ones second-guessed them. As always, disagreement and constructive critique is welcome.

The crux concerns a female character who has no part in the main story, but appears in a typically allusive and compressed digression in the XXVIIIth fitt (chapter) of the poem. As Beowulf and his companions depart from Denmark for their own home country of Geatland, the narrative turns towards the character of Hygd, the wife of the Geatish king Hygelac. She is described as wise, despite being very young, “and neither too lowly for that nor too niggardly with gifts to the Geatish people” (næs hio hnah swa þeah ne to gneað gifa Geata leodum – this I take to mean that Hygd had a proper estimate of her own position, and was neither too abject at currying favour nor too slow to give rewards for services rendered).

Having praised Hygd in these ideal terms, the poet abruptly launches into a contrasting description of a wicked queen, known to early scholars as Thryth. The basis for comparison seems to be that while Hygd graciously metes out gifts to those below her station (without being too humble towards them), Thryth is arrogant and visits savage punishment on any man of lower station who so much as dares to gaze upon her beauty.

Here is the relevant passage (lines 1931-57) as it appears in the 1909 metrical translation of Francis Gummere. Bear in mind that the ‘she’ initially discussed is Hygd, and that ‘Hemming’s kinsman’ is a reference to Offa of Angel, the husband of Thryth who eventually reforms her character.

…/ Nor humble her ways,

nor grudged she gifts / to the Geatish men,

of precious treasure. / Not Thryth’s pride showed she,

folk-queen famed, / or that fell deceit.

Was none so daring / that durst make bold

(save her lord alone) / of the liegemen dear

that lady full / in the face to look,

but forged fetters / he found his lot,

bonds of death! / And brief the respite;

soon as they seized him, / his sword-doom was spoken,

and the burnished blade / a baleful murder

proclaimed and closed. / No queenly way

for woman to practise, / though peerless she,

that the weaver-of-peace / from warrior dear

by wrath and lying / his life should reave!

But Hemming’s kinsman / hindered this —

For over their ale / men also told

that of these folk-horrors / fewer she wrought,

onslaughts of evil, / after she went,

gold-decked bride, / to the brave young prince,

atheling haughty, / and Offa’s hall

o’er the fallow flood / at her father’s bidding

safely sought, / where since she prospered,

royal, throned, / rich in goods,

fain of the fair life / fate had sent her,

and leal in love / to the lord of warriors.

He, of all heroes / I heard of ever

from sea to sea, / of the sons of earth,

most excellent seemed. / …

The general outline of this story is clear enough, as are its roots in tradition: the Thryth character would seem to fall somewhere on a spectrum between a ‘tamed shrew’ and a ‘perilous maiden’ (like Atalanta or Brynhild), who is reformed after marriage to a worthy husband. But upon closer inspection, many points of apparent certainty dissolve into mystery. We do not know whether this lady killed one man, or many, or none in the end; we do not know in what manner of force or persuasion her husband put a stop to her behaviour; and worst of all, we do not really know her name, because the one attributed to her by Gummere and other scholars may be no more than a component of a common noun.

Here’s the passage again in Old English, translated with autistic literalism (and awkwardness), with emendations and ambiguities in brackets:

… / Næs hio hnah swa þeah

(She [i.e. Hygd] was not abject for that)

ne to gneað gifa / Geata leodum

(nor too niggardly with gifts to the Geatish people)

maþmgestreona / mod þryðo [ne] wæg

(With precious treasures; she had [not] a violent temper [or, she had not the temper of Thryth; without emendation, she had a violent temper])

fremu folces cwen / firen ondrysne

(the [goodly? bold?] queen of the folk, her dreadful criminality;)

nænig þæt dorste / deor geneþan

(there were none so daring as to dare to risk,)

swæsra gesiða / nefne sinfrea

(of [her? her husband’s? her father’s?] dear companions, save for her perpetual lord [her husband? her father?],)

þæt hire an dæges / eagum starede

(that on her, by day, he gazed on her with his eyes;)

ac him wælbende / weotode tealde

(but for him slaughter-bonds he could consider destined;)

handgewriþene / hraþe seoþðan wæs

(tied [or woven] by hand; rapidly afterwards)

æfter mundgripe / mece geþinged

(after grip of hand [arrest by henchmen? mixed-sex wrestling?], to the sword he was consigned)

þæt hit sceadenmæl / scyran moste,

(so that it [presumably, the matter] the shadowed-tool [sword2] could decide,)

cwealmbealu cyðan / ne bið swylc cwenlic þeaw

(declare the killing-bale. That’s no queenly custom)

idese to efnanne / þeah ðe hio ænlicu sy

(for a lady to perform, though she be peerless;)

þætte freoðuwebbe / feores onsæce

(that a peace-weaver [i.e. an outmarried queen] should demand the life,)

æfter ligetorne / leofne mannan

(for a false injury, from a beloved man.)

huru þæt onhohsnod / Hem[m]inges maeg

(But this was hamstrung [?] by Hemming’s kinsman;)

ealodrincende / oðer sædan

(ale-drinkers otherwise said [told a different story afterwards? or, testified at the time against the false accusation?];)

þæt hio leodbealewa / læs gefremede

(that she performed less [no more?] people-harming [presumably, oppression of lower-ranked men],)

inwitniða / syððan ærest wearð

(and malicious persecutions, since first she was)

gyfen goldhroden / geongum cempan

(given, gold-bedecked, to the young champion)

æðelum diore / syððan hio Offan flet

(of noble ancestry, since she Offa’s [hall-]floor)

ofer fealone flod / be fæder lare

(o’er the fallow sea, by her father’s lore [instruction? advice? orders?],)

siðe gesohte / ðær hio syððan well

(sought upon her journey; where thereafter she well)

in gumstole / gode mære

(upon the throne of men, for goodness famed,)

lifgesceafta / lifigende breac

(enjoyed [or employed], while living, the fated span of her life;)

hiold heahlufan / wið hæleþa brego

(held high love with the heroes’ chieftain [i.e. Offa]:)

ealles moncynnes / mine gefræge

(of all mankind, so I have heard,)

þæs selestan / bi sæm tweonum

(betwixt the two seas, the very best)

eormencynnes / …

(of the great [or possibly, universal, i.e. human or imperial] race…)

I’m sure that was torture to read, but my point is simply that things are not so simple as translations imply and may not be all that they seem. Let us leave aside the majority of the passage for the moment, and concentrate on the first few lines, with a view to restoring the disputed name of the character. This post will be something of a deep dive, so feel free to scroll down to the conclusion if dead language wrangling and lost history conjecture isn’t your cup of tea.

What’s in a Name?

The old scholarly consensus, reflected in Gummere’s work, was that the name of Offa’s queen is found in the place where one would naturally expect to find it – that is to say, the half-line mod þryðo [ne3] wæg, which announces the shift from Hygd. Yet as we have seen, this is an ambiguous phrase that can mean either ‘she showed not the temper (mod) of Thryth (þryðo), or else ‘she showed not a forceful temper (modþryðo)’.4 And as we shall soon see, there are other interpretations involving other names.

Looking solely at the text, it is the interpretation as a common noun that seems most likely, for two main reasons:

Other poems have similar compound words with the verb wegan (‘to bear, to carry, to have or show [a state]’) in past tense (wæg), such as modsorge wæg (‘showed heart-sorrow’) and higeþryðe wæg (‘showed mind-arrogance’, used of an insolent woman). This suggests that the phrase modþryðo wæg is a variant of a traditional formula that is not used anywhere else to introduce a name.5

The preceding word maþmgestreona (precious treasures) is stave-rhymed or ‘alliterated’ with mod þryðo wæg, which clues us into the fact that mod and not þryðo is supposed to bear primary stress. This suggests that modþryðo is a compound word (because Old English words are nearly always stressed on their initial syllables), and at the very least that þryðo is not a name.

All in all, this looks like a pretty devastating case against the name Thryth (although I’ll show you in a minute why it isn’t). But what are the alternatives? Many translations (including the famous Heaneywulf, and the ignorant woke parody Headleywulf) follow the many scholars who chose to hedge their bets and render the name as ‘Modthryth’.6 But such a name is not attested elsewhere among the many Anglo-Saxon female names derived from the word þryð, and in any case it also falls foul of the argument from traditional formula.

Another option (plumped for by Tom Shippey in his recent scholarly translation of Beowulf) is to identify the true name as ‘Fremu’, the first word in the following half-line fremu folces cwen. At least this word bears stress and stave-rhyme, but it is still squeezed into the line in such a way as to make its interpretation as a name unlikely. Earlier scholars read it as a somewhat obscure adjective, freme7, which they assumed to mean ‘goodly, excellent’ (if it is related to noun fremu, ‘benefit’) or ‘bold, vigorous’ (if it is related to adjective from, ‘bold’). Both of these meanings might easily apply to Thryth, since she is ‘bold’ enough to murder men for looking at her, and yet is ‘goodly’ or ‘excellent’ in physical terms (note the later description of her as ænlic, ‘peerless’). Alternatively, the phrase fremu folces cwen could still apply to Hygd, if we read the half-line preceding it ‘she had not a violent temper’ or ‘she had not the temper of Thryth’.

Eric Weiskott (in “Three Beowulf Cruces: healgamen, fremu, Sigemunde”, 2011), after examining the many problems with ‘Modthryth’ and ‘Fremu’, concludes that “the simplest explanation is that the poet never names the queen”. One example of a translation that plumps for this solution is that of Frederick Rebsamen. Yet to do so is to attribute to the Beowulf-poet an uncharacteristic lapse in poetic skill, since without the name of Offa’s queen the whole passage reads like a self-contradictory and confusing discourse on Hygd.

My view on the switch of topic between Hygd and Thryth is precisely opposite to this: I think that it represents not a lapse of skill, but an exemplar of that skill. It is one so subtle as to have sailed right over the heads of modern translators – although the early ones like N.F.S. Grundtvig and Frederick Klaeber, who established the old scholarly consensus, came closest to catching its drift.

The Lies of Two Offas

As we have seen, these early scholars would have had little reason to identify the name as Thryth based on the text alone, but did so because they had found corroborating evidence in another text concerning the Anglo-Saxon era. This text is the twelfth-century Vitae Offarum Duorum, or “Lives of Two Offas” – that is to say, the semi-legendary migration-era ancestor Offa of Angel, and his eighth-century English descendant Offa of Mercia.

This work presents the life of Offa of Mercia as a series of parallels with that of his semi-legendary ancestor. Both Offas are mute and apparently mentally-retarded in childhood (a traditional motif applied in different ways to many Germanic heroes, including Saxo’s Amleth and even Beowulf). Both end up averting threats to their fathers’ kingdoms in youth and then going on to rule as kings. Most importantly from our perspective, both marry beautiful foreign princesses exiled from their homelands – but in this case, with very different results.

The first Offa’s queen much resembles the character of Constance in Chaucer’s “Man of Law’s Tale”. Banished from her homeland to a forest by her father for refusing his incestuous advances, she turns out to be both beautiful and virtuous. Due to a mix-up with false letters caused by the scheming of her father, she is briefly banished from Offa’s court, but ends up being vindicated and reconciled with her husband. Strangely enough, this queen is never named at any point in the story.

The second queen, that of Offa of Mercia, only partly parallels the first. She too is driven out of her homeland by a male relative, the Frankish king Charles the Great, but this time on a boat adrift at sea and as a just punishment for an unspecified criminal act. She calls herself Drida – presumably a Latinization of Thryth – and claims that she was banished for refusing marriage to men of lower station (an early warning sign of her haughtiness). Though Offa’s mother and father are aware that she is “boastful and passionate”, “impertinently contemptuous”, “sows words of discord”, and is “a little hussy utterly unworthy of the king’s embrace”, she is very beautiful and manages to captivate Offa into marrying her.

Later in the narrative, King Offa has established his rule, and Thryth has become known as “Cwenthryth, that is Queen Thryth” (Quendrida, id est regina Drida). She is a “greedy and crafty woman”, “swelling with pride because she came from the race of Charles”, and persecutes the king’s advisors “by setting a woman’s mousetraps for them”. Because Offa has promised their daughter to King Æthelberht of East Anglia, whereas his wife wants to marry her off to “men overseas” “to the detriment of the kingdom of the Mercians”, she tries to persuade her husband to kill Æthelberht. After Offa refuses to do such a deed, she goes ahead and kills Æthelberht herself – suffocating him to death with the help of her officers, who eventually behead him, upon which the author comments that he was “entangled in a woman’s snares like John the Baptist”. For this she is banished by Offa, without eventual reconciliation (though the narrator adds that “perhaps, if grace were bestowed on her by heaven, she would be able with penance to wipe out the stain of having committed such a great crime”), and at last slain by robbers who throw her into a cesspit.

Evidently this is not the same narrative with which we are presented in Beowulf. But it should be obvious enough why early scholars found the connection too strong to be ignored, and lit on the name Thryth as the most likely out of a line-up of doubtful options. Modern scholars, perhaps owing to a sharper but narrower focus, have largely abandoned this view; thus R.D. Fulk, in “The Name of Offa’s Queen: Beowulf 1931-2” (2007)8, goes so far as to dismiss the connection with the Lives entirely:

The strongest evidence for the standard view, the supposed parallel to the tale in the Vitae duorum Offarum (ca. 1200), describing the wickedness of (Quen)Drida, wife of Offa's English descendant Offa II, the great king of the Mercians, is vitiated by the realization that this woman's name actually was Cynethryth. Thus the similarity in the names cannot be said to evidence transferral of the tale alluded to in Beowulf to the wife of Offa's descendant; and once the coincidence of names is accordingly seen to be irrelevant to the question of the connections between the tales, the remaining resemblances are so feeble that the assumption of any notable relation between the Vitae and Beowulf must be abandoned.

Indeed, the real name of Offa of Mercia’s wife was Cynethryth, not Thryth or Cwenthryth – this is attested by the evidence of coins minted in her name and charters that she witnessed during the reign of her husband. But inquiring minds should not be content to let the matter rest there. History has known many great liars, and discrepancies like this should begin to arouse our suspicion that the writer of the Lives of Two Offas was among them.

Let’s start with the obvious point that this is a late text, far removed from Anglo-Saxon England, and cannot hold a candle to Beowulf in terms of historical verisimilitude.9 The most glaring symptom of this is that its author locates the kingdom of the first Offa and the events of his reign in England – forgetting entirely that he hailed from Angel, the original Continental home of the English, which was reportedly left depopulated after the mass migration to Britain. We can hardly expect much more from such a text than “feeble resemblances” to earlier and more valuable sources, but that is no good reason to dismiss those resemblances.

Yet there is more than ignorance corrupting the tradition here. On the subject of the murder of King Æthelberht in 794, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says only that “Offa the king of Mercia ordered King Æthelberht’s head struck off” (Offa Miercna cyning het Æþelbryhte rex þæt heafod ofaslean), making no mention of Cynethryth’s involvement. Given the overweening power-jealousy of Offa, such an act does not seem wholly out of character for him.10 But the Lives of Two Offas was written by a monk from the abbey of St. Albans11, a house that Offa of Mercia had founded. The murdered Æthelberht was a canonized saint, and the Lives author had an obvious hagiographical motive for displacing the guilt of his death onto someone other than Offa himself. For this purpose he had only to embellish and exaggerate an already-existing tradition, according to which Cynethryth had instigated her husband to commit the murder.12

All of this is well-known and generally accepted. But the scholarly articles assessing and debating the connection of the Lives with Beowulf tend to summarize the text all too briefly, giving little idea of the way in which its author props his propaganda with bits and pieces quarried from other parts of tradition. His distortion of Cynethryth’s name to Cwenthryth was surely no accident, for this was the name of a later Mercian princess who is also supposed to have murdered a canonized saint.13 Obviously his intent in this was to transfer the odium of this name to Cynethryth, and play on the ease with which popular memory might have conflated the two. Why then should he not have played the exact same trick, for the exact same reason, with his attribution of the name Thryth to Cynethryth?

If this were in fact the name of the first Offa’s wife – and one that carried an association with intrigue, false accusation and murder – then this would certainly answer some questions. It would explain why this queen goes without a name throughout the whole narrative, even as lesser personages (such as Offa’s short-lived duelling opponents) are named. It would also explain why she is a doppelganger for the character of Constance in Chaucer’s “Man of Law’s Tale” – much of which is also set in Anglo-Saxon England, but with the role of the husband played not by Offa of Mercia but by Ælla of Northumbria, who is also the husband in other versions of the tale.14 The chance marriage of both Offas to two wicked queens called Thryth would not have been swallowed even by the most credulous audience.

My hot take is that the author of the Lives, in his quest to blacken the name of Cynethryth, has split the original personage of Thryth into two. The traits of the later virtuous Thryth have been concentrated into the first Offa’s nameless wife, and padded out with bricolage from another tale of a foundling wife involving a different Anglo-Saxon king. Meanwhile, the initial murderous Thryth has been transplanted into the role of the second Offa’s wife, bringing along with her not only her name but also number of her traditional traits – such as her arrival by sea, her haughtiness, and most usefully her modus operandi of binding and (presumably) beheading.

The upshot of all of this is that the Lives can indeed be taken as evidence for the name Thryth, as early scholars believed. And now we are in a position to understand why her introduction in Beowulf represents an exemplar of skill and not a lapse by the poet. I propose that the line modþryðo [ne] wæg is a pun on the traditional formula,15 which obviates the need for a conventional introduction.

The two meanings of the pun can be separated out as follows (emendations and clarifications in square brackets), starting with the surface meaning:

modþryð[e] [ne] wæg

she had not a violent temper

fremu folces cwen

the [goodly] folk-queen

firen['] ondrysne

[nor] fearsome criminality

And now the underlying meaning:

mod Þryð[e] [ne] wæg

she had not the temper of Thryth

fremu folces cwen

the [bold] folk-queen

firen['] ondrysne

[her] fearsome criminality

In the first reading, the object of the verb wegan is modþryð[e] ‘violent temper’ in accusative case; in the second, it is mod ‘mind’ or ‘inner state’, and the name Þryð[e] ‘Thryth’ is a proper noun in genitive (possessive) case. In both readings, firen[']16 ondrysne is a second object of wegan and refers either to the crimes that Thryth committed, or those that Hygd did not. Fremu folces cwen is a subject of wegan in both readings, and describes Schrödinger’s queen: in the first reading it is an extension of the earlier use of hio ‘she’ to refer to Hygd, whereas in the second it reads most naturally as an interjected half-line referring to Thryth. The attribution of a double meaning to freme, which is presumably related to fremu ‘benefit’ and thus means something like ‘goodly’, is made on the assumption that this was a deliberate choice of a rare word that would also have connoted from ‘bold, firm, vigorous’.

Admittedly this sort of complex punning on names is not found elsewhere in Beowulf. One possible reason for its use here would be that the poem was composed under Offa of Mercia17, and that the poet was either making a dig at Cynethryth (note the close association of the words þryð and cwen here) or wished to avoid mixing his praise of the king’s ancestor and his control of his household with any unintentional insult towards his wife. As the present author well knows, he who wants to tell soð æfter riht (truth according to right) has to pick his battles when giving offence to power.

Unfortunately the pun is very difficult to translate into modern English, due to the loss of the word thrith and all its derivatives from our language. The best that I can manage is something like this:

...She was not abject for that [i.e. Hygd], Nor too niggardly with gifts for the Gothish men, With dear treasures. Not so dreeded was her temper As that vibrant folk-queen of fearsome crimes...

Dreeded is of course a pun on Drida, the Latinized form of Thryth. The word vibrant in the next line, which corresponds to the ambiguous freme, is also chosen for its dark undertone of near-homophony with violent.18 Other such words could be chosen; one alternative, with a looser paraphrasing, might be:

Not niggardly with gifts to the Gothish men, With treasures not thrifty; not tempered like that other Captivating folk-queen of fearsome crimes...

Admittedly, the fact that such a translation would come closest to the original in meaning does not mean that it is at all suitable for a modern audience, who cannot be expected to understand all this antiquated septentrional nudging and winking. So perhaps we should be content to render the crucial half-line as she was not tempered like Thryth, she had not Thryth’s mood, etc. Anything as long as we don’t have to call her ‘Modthryth’, ‘Fremu’, or worse, nothing at all.

As we have said, there are many more enigmas and controversies in the passage beyond the first few lines (as well as much false and distorting ‘revisionism’ by feminist pseudo-scholarship, as is only to be expected given the subject matter). But given the amount that has been written in academia on the subject of the name alone, I think that its restoration to Thryth is worth a post in itself. We shall deal with everything else, including the retranslation of the passage, in the second installment.

Such as the Finnsburg episode, the Grendel’s mother character, and two cruces in the Grendel fight.

This word sceadenmæl perhaps refers to a ‘shadow-patterned’ or what we would call a ‘damascened’ blade, which is also what seems to be described by other words referring to ‘wavy’ and ‘decorated’ swords in this poem. See here for more details.

The insertion of ne, ‘did not (show a violent temper etc.)’ is defended by Tolkien in the commentary to his posthumously published Beowulf (p.272):

In defence of the emendation mod Þryðo [ne] wæg we must observe: ne (or any negative particle in any language) appears in logic to be overwhelmingly important, exactly reversing sense, so that it is difficult to conceive of its omission. As a matter of fact (i) it is in writing a small easily omitted word on mere mechanical grounds, especially as scribes do not follow the detail of sense (and the scribe here, as always when faced with legendary names, was plainly at sea); (ii) even in speech it is often reduced to a very fugitive element in spite of continual linguistic renewal, and even then is sometimes accidentally omitted.

Without this emendation, the half-line in question reads ‘she [i.e. Hygd] showed a violent temper’ or ‘she showed the temper of Thryth’, which is obviously nonsensical as it removes the sense of contrast between Hygd and Offa’s queen.

The word mod (ancestor of modern English mood) means ‘mind’, ‘heart’ or ‘inner state’, thus can be felicitously translated in this case as ‘temper’; þryþ means might, force or power, usually of a violent nature (so that, for example, Thor’s ‘mighty hammer’ in the Lokasenna is called a þrúðhamarr in the related Old Norse language). That a Germanic woman should have had such a martial name as Thryth is nothing out of the ordinary, and does not necessarily imply an Amazonian side to her, though in this case there is no ruling it out.

If this is so, the correct form should be modþryðe [ne] wæg ‘had [not] a violent temper’, as the noun is modþryð and the -e ending marks the accusative (direct object) case. Note however that if the phrase is understood as mod þryðe [ne] wæg ‘had [not] the temper of Thryth, with þryð treated as a name in the genitive (possessive) case, the ending would still be -e. The ending -o seems a plausible enough misspelling in either case.

This reading requires us to treat modþryðo ‘Modthrytho’ as a proper noun and the subject of wegan. Yet to my knowledge, none of the other many female names derived from the word þryð have a final -o, and this is surely better explained as a misspelling of a case-ending.

In feminine form fremu to modify cwen.

Although I was not able to obtain this article by request, its abstract is available here (along with an option for indepdent researchers to obtain it by payment, but the price was unfortunately too steep for this one). Judging from this admittedly superficial overview, many of the other arguments made in it seem quite weak as well: there seems to be no reason why the mod of Thryth should be interpreted as her ‘arrogance’ rather than her ‘temper’ or ‘inner state’, and nor is there any reason why freme should be seen as pejorative just because it is applied to Thryth, since descriptors like ænlic ‘peerless’ are applied to her as well. I would be grateful to anyone able to summarize or share the entire article.

For more details on the unusual historical verisimilitude of Beowulf and its value as a historical source, see Tom Shippey, Beowulf and the North before the Vikings.

In The Age of Arthur, p.331, John Morris remarks that “Mercian power died of its own greatness” under Offa, who destroyed the local underpinnings of his state in an effort to emulate the Romanist absolutism of his contemporary Charlemagne:

Offa’s overpowering majesty induced him to cut away the props on which it rested. He abolished the underkings, executing the last king of the East Angles, ending the Kentish monarchy, reducing the rulers of Sussex to the status of dux, introducing his dependants on the thrones of Wessex and Northumbria; and called himself “king of the English”, no longer, like his predecessor, of the southern English alone.

The murder of Æthelberht (emphasized) fits snugly into this power-arrogating career, though of course the influence of Cynethryth on all of it is unknown.

Possibly Matthew Paris. The immediate source for the author was apparently Roger of Wendover, also based at St Albans, who gives a similar but less exaggerated account of Æthelberht’s death at the hands of ‘Quendritha’ (Cynethryth). Some of my references to ‘the Lives author’ or ‘St. Albans author’ in the text can also be taken as applying to him, as well as to any other links in the chain of this pro-Offa, anti-Cynethryth tradition.

The existence of such a tradition is inferred from the early twelfth-century Hereford Passio s. Athelberti, summarized in Richard North’s The Origins of Beowulf (pp.241-5). In this version of the tale, ‘Kynedritha’ is provoked to anger by her daughter’s comment that Æthelberht is a better man than Offa, and encourages Offa to kill him on the grounds that he is a threat to his rule. Offa then delegates this task to a certain ‘Winberhtus’, who binds the victim with chains and tortures him before beheading him with a sword. The relative reliability of this account (that is to say, relative to the very unreliable St. Albans one) is implied by the lack of any attempt to exonerate Offa, the greater closeness of the name Kynedritha to Cynethryth, and the attestation of a certain Wynberht as a witness to three extant Mercian charters.

Her name is given as Quendrida in the part of William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle that concerns the history of the Mercian kings.

Another version of the tale is found in the Confessio Amantis of John Gower; the apparent source for both Gower and Chaucer is the Anglo-Norman chronicle of Nicholas Trivet, which traces the story further back to “ancient chronicles of the Saxons” (see Originals and Analogues of Some of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, ed. Furnivall et al., p.2.). Presumably these sources also named Ælla as the husband; had they named Offa, it is difficult to see why Trivet should have substituted Ælla, since the switch neither adds nor subtracts anything much from the story. Obviously the same cannot be said for the attribution of Roman and not Anglo-Saxon ancestry to the idealized heroine, though this too may have been a feature of the traditional tale (given e.g. the theme of the boat adrift at sea).

The idea of a deliberate double meaning seems not to be in fashion, or has not been proposed in this way before; those who undertake to solve the crux seem to hold in common the assumption of some single meaning that has only to be discovered by reasoning, emendation, etc. Perhaps scholars have been wary of reading ‘too much’ into poetic formulas since Milman Parry proved that many Homeric ones are chosen purely for convenience; but there is plenty of evidence that this does not apply to Anglo-Saxon literary poetry, which stands at a greater distance from oral tradition than Homer. For evidence of punning elsewhere in Beowulf, we need only consider the constant play on the similarity of gaast ‘spirit’ and gast ‘guest’ in the descriptions of the monster Grendel, or the use of the term Sige-Scyldingas ‘Victory-Shieldings’ to describe the Danes at the very moment in which Beowulf recounts their victimization by this monster.

This apostrophe signifies that the accusative -e ending of firen ‘crime’ has been omitted in the text because it runs into the vowel of the following adjective ondrysne ‘fearsome’.

Although I have not yet looked deeply into the question of when and where Beowulf was composed, it would seem that the dating of the poem to the 8th century of Mercian ascendancy in England is supported by several respected scholars including Tolkien, Shippey and Fulk. If the poem were written under Offa’s rule, this would certainly explain its effusive praise of his ancestor and knowledge of his genealogy (which is recounted just after the passage in question), as well as his lack of animosity towards the Danes (who, in the form of vikings, would become the scourge of England in the following centuries).

Made all the more poignant for some of us by its frequent use in media and state propaganda in Britain to describe areas of cities relatively denuded of white people.

Fascinating stuff - I had never heard of the Two Offas text. It seems to me that the poet is quite capable of the subtle punning you argue for here.

Regarding the date of Beowulf, Leonard Neidorf writes confidently and, I think, convincingly, for an 8th-century date (and Mercian provenance). I have only read bits of his argument in various of his articles; I'm looking forward to reading The Dating of Beowulf: A Reassessment for a fuller view.

Fulk's History of English Meter seems like it would be a good source for establishing a relative chronology of OE verse, but I haven't gotten my hands on that one yet either.