In a previous post on oral theory, we told the story of Milman Parry, who studied the formulaic phrases in the Iliad and Odyssey (e.g. “swift-foot Achilles”, “rosy-fingered dawn”, “wine-dark sea”) and worked out that Homer was able to compose his verses in the moment of performance. In doing so, he rediscovered a long-lost poetic technique, which we shall hereafter call by the name recomposition. Recomposition is neither recital from memory nor free improvization, but something inbetween: the poet memorizes a storyline, but tells it through scenes and phrases constructed at speed on the basis of traditional models.

We saw how Parry and his assistant, Albert Lord, travelled to precommunist Jugoslavia and recorded thousands of oral poems composed in this way to the music of the fiddle-like gusle. We saw how Lord, who wrote up and expanded on the theory in his book The Singer of Tales, began to speculate on its application to the textual relics of lost traditional poetries. Finally, we saw how Francis Magoun tried to apply the theory to Anglo-Saxon poetry – and did not exactly succeed.

Let’s refresh our poor literate memories on that last part:

One of the most obvious applications of oral theory is to the study of Old English poetry written down in the Anglo-Saxon period. Beowulf certainly rings like a traditional tale, and is full of formulaic repetitions – half-lines like goldwine gumena (gold-friend of men, used of a king), duguþ ond geogoþ (veterans and youths), etc., and full lines like Beowulf maþelode / bearn Ecgþeow (Beowulf spoke / son of Edgethew). Not only the meter but also many of the formulas are shared by other poems from the same period, suggesting a common word-hoard of traditional diction such as that of the South Slavs. So the Old English scholar Francis Magoun, in the early 1950s, marched in to annex this territory with an article entitled “Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry”.1

Alas, the theory met with an unexpected reverse. Magoun, imitating Parry, had established the ‘oral’ character of Beowulf by sampling twenty-five lines and counting the formulas… But as Larry Benson showed in his counter-argument, “The Literary Character of Anglo-Saxon Formulaic Poetry”, Old English translations of Latin works such as The Phoenix and The Meters of Boethius are no less filled with traditional formulas. The existence of ‘transitional texts’ could no longer be denied; and this presented a problem for the oral theory, given that everything we know for sure about premodern oral traditions comes from written texts.

By ‘transitional text’ we mean a literary work that preserves the telltale signs of traditional recomposition, such as formulaic phrasing and use of type-scenes. Lord had initially wanted to think that there was no such thing as a transitional stage between orality and literacy, and that each text could be sorted into either one category or the other. In this view, ‘traditionalist’ poems like Beowulf and Widsith must have been dictated to scribes by illiterate performing scops, just as Parry’s texts were dictated to him by guslars. But Lord had to rethink this in the face of pushback in the Anglo-Saxon field; and a later oral theorist, John Miles Foley, could write in 19992 that “scholars and fieldworkers generally concur that the supposed ‘Great Divide’ of orality versus literacy does not exist.”

Obviously the ‘default hypothesis’ on literary texts, including Beowulf and Widsith, should be that they were composed pen in hand. The question that interests us is whether, and to what extent, these texts preserve the oral-traditional forms that must have existed among Anglo-Saxons before they were converted to literacy. In particular, we want to know whether the meter of these poems was the same one used by preliterate scops to compose in the moment of performance.

Why do we want to know this? Because we want to restore traditional poetry, of course, and have a hunch that a modernized form of the Old English meter could be the medium of choice for this. If the verse-style of Beowulf represents the English equivalent of the Homeric hexameter and South Slavic decasyllable, then modern revivalists need look no further. But this is by no means a foregone conclusion! It could be that the preliterate Germanic tradition was one of recital from memory3, not recomposition; and perhaps Beowulf and other such poems represent nothing more than a literary genre with traditional residues.

It seems that we must treat three questions here:

Whether there is any evidence for recomposition in Anglo-Saxon culture;

Whether the style of the texts proves the influence of oral composition;

Whether the meter of the poems reflects a recompositional, memorial, or literary tradition.

I warn you in advance, none of these lines of inquiry will lead us to a conclusive answer. But once we have followed them as far as they go, we should be able to hazard some educated guesses.

Black and White Minstrels

Just now I spoke of “the oral-traditional forms that must have existed among the Anglo-Saxons before they were converted to literacy”, and “the Germanic equivalent of the Homeric hexameter and South Slavic decasyllable”. But is there any real evidence that the Anglo-Saxons, and Germanic peoples more widely, had a tradition of recompositional poetry like the Ancient Greeks and the South Slavs?

We might not go far wrong by simply assuming that they had. In How To Kill A Dragon, Calvert Watkins traces some common poetic themes and formulas scattered among the daughter-languages of Proto-Indo-European from Ireland to India, and the evidence seems to point to a tradition of oral epic among the Bronze Age speakers of that language. But this amounts to ‘groping in the mists of Aryan prehistory’, and we must do better than that.

Fortunately, we have a certain amount of evidence from the time and place in question. The best one-stop shop for that evidence is Jeff Opland’s Anglo-Saxon Oral Poetry, and it appears all the more compelling for the fact that the author was trying to deboonk the analogy of scop and guslar. I can recommend this book only to those prepared to analyse it critically, separating fact from opinion at every turn; those inclined to idle reading or excessive deference to scholars will only be led astray.

Much as the regular features of a pretty girl seem all the fairer in comparison with the lopsided looks of an ugly one, the scop-guslar analogy is burnished in this book by juxtaposition with Opland’s izibongo analogy. Izibongo is the praise-poetry of the Bantus of South Africa, which according to Opland is primarily memorial among the Zulus and improvizational among the Xhosas. It might have made an interesting basis for compare-and-contrast with Anglo-Saxon poetry, were it not for Opland’s transparent desire to pretend that the two are more similar than they actually are. For example, he claims at every turn that the scop was a eulogistic ‘tribal poet’ just like the imbongi, but most of his sources point rather to a harp-playing singer of heroic tales much more resembling the guslar.4

Let’s play a little game of odd-man-out. Here is an eyewitness drawing of a 19th-century imbongi, apparently in performance. The first thing that strikes you is the fact that he is wearing an animal mask and skins, which may or may not be related to an early shamanic function of this form of poetry. Note that he is pictured standing, in movement, holding sticks or spears, and not playing any sort of musical instrument (though the Xhosas and Zulus have many).

Next, here is a representation of a South Slavic guslar just such as those recorded by Parry, seated and singing to the sound of his stringed instrument:

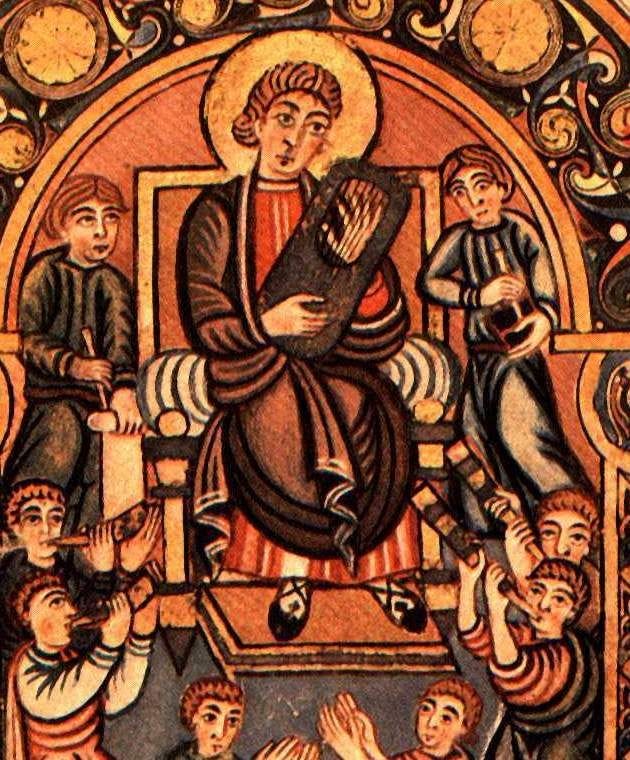

And finally, here is an illustration from an Anglo-Saxon psalter, depicting a figure that resembles the guslar as much as he contrasts with the imbongi. Admittedly we cannot call this a picture of a scop, because it is supposed to be David, the harp-playing poet-king of ancient Israel and Judah. But note that the illustrator has portrayed him along local and contemporary lines, with Northern European features and a Germanic lyre of the same type excavated at Sutton Hoo.

It is well enough known that medieval depictions of Classical and Biblical battle scenes display the castles and armoured knights of contemporary Europe; and in light of this, one would think that what this picture really represents is the traditional idea of the scop in Anglo-Saxon culture.

This is not necessarily so, as the illustrator may have intended to portray King David solely in his capacity as a harpist. But there is no shortage of evidence that scops also played harps – or rather, what we would call lyres – as they recited poetry. In lines 103-5 of Widsith, the eponymous scop (whose name means ‘wide-journeyed’) narrating the poem describes his performance thus:

Đonne wit Scilling / sciran reorde

(then I and Scilling, with a clear voice)

for uncrum sigedryhtne / song ahofan

(Before our victory-lord raised up a song)

hlude bi hearpan / hleoþor swinsade

(Loud to the harp, the din resounded)

The meaning of Scilling is unknown, but it seems to be a person or pet name for an object, to judge from the use of wit and uncer (‘we two’ and ‘the two of ours’). Opland (p.211) comments that it “would be a reasonable name for a minstrel’s harp”, but “could also be the name of a harper who accompanied Widsith’s performance.” I find the former interpretation much more likely in light of a passage in Beowulf (lines 89-91), which once again refers to a scop and a harp and a song:

Hludne in healle / þær wæs hearpan sweg

(Loudly in the hall; there was the sound of the harp,)

swutol sang scopes / sægde se þe cuþe

(The clear song of the scop; he said what he knew)

frumsceaft fira / feorran reccan

(About the beginnings of man, telling of long ago)

Opland comments (p.193; emphasis mine):

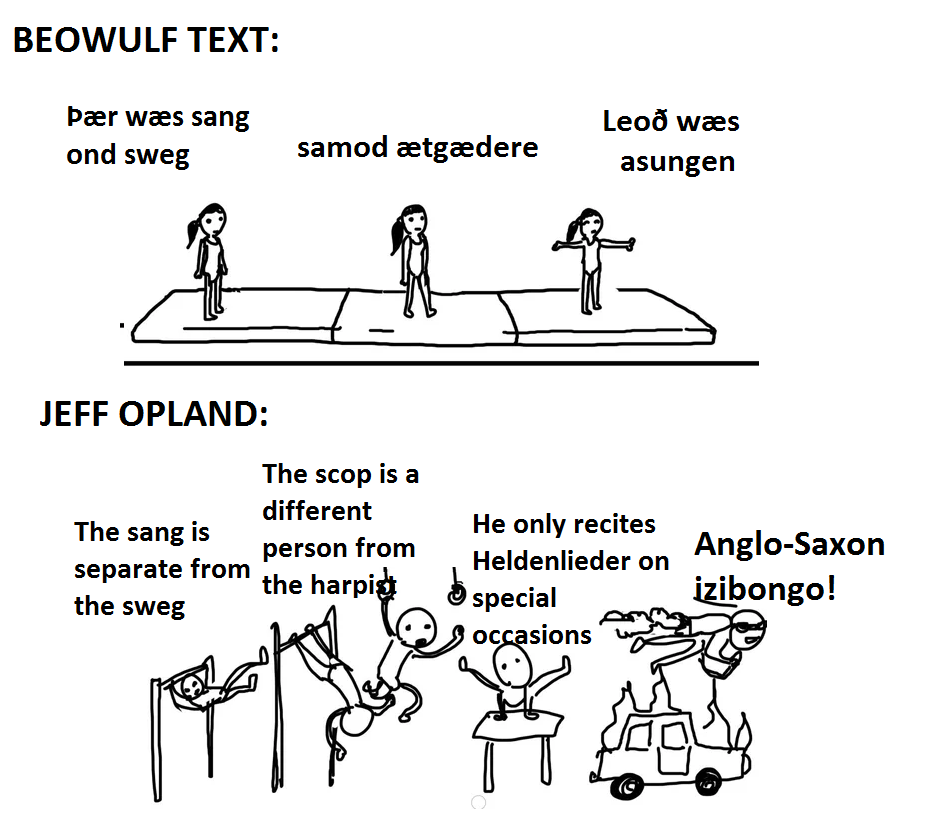

It is usually assumed that lines 89-91 introduce a summary of a poem on the creation produced by the scop to the accompaniment of his harp. The Old English poetic technique of variation being what it is, that is certainly a justifiable reading. However, it is also possible that not one but three activities are referred to here: the playing of the harp, the performance of the scop, and the narrative of the creation by someone who knew how to tell this story.

This seems highly unlikely! At no point do we hear the word hearpere (‘harpist’), and most scenes in Beowulf are not so badly staged as to make it impossible to tell who is performing basic actions in them. But Opland has to disintegrate the scop into three people – a poet, a musician, and a storyteller – in order to deny the obvious analogy with the guslar and uphold the more questionable one with the imbongi.

Perhaps the clearest statement on this is found in another passage elsewhere in Beowulf (lines 1063-68 and 1159-62), in which a scop at a king’s court strikes the lyre and sings a heroic tale:

Þær wæs sang ond sweg / samod ætgædere

(There was song and sound [i.e. of strings], united together)

fore Healfdenes / hildewisan

(in front of Halfdane’s war-general [i.e. Hrothgar, the Danish king])

gomenwudu greted / gid oft wrecen

(the gaming-wood [i.e. a harp or lyre] struck, a story often told;)

ðonne healgamen [geswac?] / Hroðgares scop

(then the hall-revelling [or hall-joy] [stopped?]; Hrothgar’s scop,)

æfter medobence [?] / mænan scolde

(behind the mead-bench [?], had to tell)

be Finnes eaferum / ða hie se fær begeat…

(about the followers of Finn, who were caught in a surprise attack…)

…Leoð wæs asungen

(The lay [i.e. poem, song] was sung,)

gleomannes gyd / gamen eft astah…

(the tale of the gleeman [i.e. singer or minstrel]. Revelry began again…)

This seems pretty open-and-shut to me; and note also that the tale of Finn (which you can read in full here), is not a piece of praise-poetry but rather a tale of tragic heroism. Now, at the risk of indulging my cruel streak, I shall give you some of the tragi-heroic contortions by which Opland (p.195-6) tries to distort the meaning of the passage in order to uphold his own theory:

Line 1063 says that there was sang and sweg together. Since line 89 associated sweg with the harp and line 90 associated sang with the scop, line 1063 might be taken to mean that harper and scop were one and that the sang and sweg were simultaneous, or that harper and scop were separate individuals but that they performed a duet [!], or that harper and scop were separate and they performed separately but at the same point in the proceedings. The latter would not entail a forced reading of “samod ætgædere” [united together]: harper and poet vie one against the other at Athelstan’s coronation feast [a reference to a source discussed elsewhere in the book], and one could say that there were both harping and poetry together before Athelstan. … Taken as a unit on its own, lines 1063-65 could serve as a signal to the audience that the poet is describing joy in the hall: as in the previous passages we just quoted, there is the þær wæs formula (1063), there is joy (gomen here, rather than dream) and there is sang; as in line 89, there is a harp and sweg. While all this joy was current, then (1066) the scop had to utter hall-joy about the followers of Finn (“healgamen…mænan scolde be Finnes eaferum”). I take this to mean that, as part of the entertainment, the scop was requested to narrate the story of how Finn and his men were caught in a surprise attack when it was his fate to fall in Frisia; 1066-70 is then the request, and at 1071 the poet begins his summary of the scop’s performance, which is produced solo, free of harp accompaniment. It is not normally his function to narrate stories [note that there is no evidence whatsoever for this statement in the text], but he has the ability to do so, since the eulogistic form can be turned to explicit narrative; Hrothgar’s scop, a eulogiser [again, there is no backing for this in the text], can produce a narrative on demand, just as Caedmon [another oral poet] complied with the request to produce narratives. Reference to Finn and his exploits might be made in the course of his day-to-day performance of eulogies, but perhaps in honour of the Geats [i.e. visiting guests], Hrothgar asks his scop to turn his talents to the story of Finn… The episode as summarised is elliptical and allusive: the audience would know the story, and in any event, this is just how a eulogiser would handle the story within his tradition.

At the end of this mental Houdini-act (certainly the worst example of many in the book), Opland has the honesty to say that “this is admittedly leaning rather heavily on the evidence” and that “it must be readily conceded that the text would certainly support the generally accepted reading that the scop played a harp to accompany his narrative song about Finn.” And to this I am tempted to add, no shit.

If this is the best that a big-name scholar of oral poetry can come up with in an attempt to disprove the scop-guslar analogy, I think the rest of us can safely assume that it is pretty damned solid after all.

What is trickier to prove is that this scop practiced recomposition like the guslar, as opposed to verbatim recital from memory. There are no grounds for assuming that a preliterate poet must be a recompositionist as opposed to a memorizer; on the contrary, many preliterate poetic traditions are primarily memorial5, including the ancient Hindu tradition of reciting the Rig-Veda (which has the two relevant credentials of extreme antiquity and Indo-European origins).6 Once again we must rely on the evidence of the texts, while bearing in mind that the literates who wrote them may not have possessed much insight into the creative process of the oral poet.

One obvious place to begin is with the story of Cædmon, an illiterate cowherd who was reportedly blessed with miraculous poetic ability. In his discussion of this poet in the fifth chapter of his book, Opland makes much of the fact that his first composition was a eulogy (specifically, a hymn in praise of God); but it seems from the account of Bede (pp.109-110) that the special ability of Cædmon was to take anything in Scripture and reword it into English poetic language (scopgereord). As Opland admits (p.119), these compositions included narrative as well as eulogy, although they do not seem to have been accompanied by harp and song:

When he [Cædmon] appears before [the abbess] Hild’s monks, however, they read a passage of Scripture to him and ask him to turn it into poetic form (“exponebantque ille quendam sacrae historiae siue doctrinae sermonem, praecipientes eum, si posset, hunc in modulationem carminis transferre”). The terms of reference of this assignment are much more rigid than those offered him by his heavenly visitor [i.e. the angel or divine being who appeared to him in a dream and inspired him with his first hymn]. Hild later instructs him to be taught the whole course of sacred history (“iussitque illum seriem sacrae historiae doceri”), and it is this that he turns into “carmen dulcissimum” after ruminating like a clean animal. The list of subjects of Cædmon’s poems that Bede supplies supports the view that in the course of his monastic career Cædmon produced in English poems that followed his scriptural exemplars – poems that, in other words, are likely to have been narrative, even though, like his hymn, their function might still have been to exhort his hearers to a love of God.

The question is whether this rewording of Scripture by Cædmon was accomplished on the spot, or involved a longer process of composition, memorization and finally verbatim recital. Opland makes the case for memorization (pp.113-4):

Bede does say in his introduction that Cædmon turned whatever he heard into charming poetic form quickly (“post pusillum”), implying little delay, but this is a relative term; on the two occasions when Bede gives an account of such delays, they are in fact quite long in duration: the monks test his ability by reading a passage to him, he goes home, and only the following morning returns with a finished product; and later Cædmon is likened to a clean animal memorising and ruminating over the story… All indications are that Cædmon generally required a period of meditation for his compositions… One might well question Bede’s ability to discriminate between improvisation and memorisation, but there can be no doubt that the text supports the view that Cædmon was a memoriser: hence it is worthy of remark that Cædmon’s hymn did not derive from a memorial tradition, that Cædmon produced verses that he had never heard before (“coepit cantare…uersus quos numquam auderiat”).

Assuming that by “improvisation” Opland means recomposition, i.e. what Lord referred to as “composition in performance”, this passage betrays some misunderstanding of that concept on his part. Most of the recomposing guslars described in Singer of Tales also needed a day’s time or so to mull over new songs (to say nothing of new compositions, which are little discussed in that book, though admittedly one guslar managed to make up a song about Parry on the spot). Moreover, they too ‘memorized’ their poems at the level of the story, and believed themselves to be reciting them ‘word for word’ (to say nothing of what their audiences thought).

No clear-cut distinction was made between memorization and recomposition before the modern oral theory, so vague references to recital from memory in primary sources can tell us little or nothing. On the whole, though, I agree with Opland that Bede’s account is ambiguous, and that Cædmon was most likely a memorizing poet.7

Our second relevant source, however, is not so ambiguous. We must take it with a pinch of salt, because it comes from lines 867-77 of Beowulf, whose author (as we shall see in a moment) was likely quite far removed from the world of scops and song-poetry. Assuming, however, that this poem conserves something of the memory of the scop in literate Anglo-Saxon culture, what these lines seem to tell us is that he was capable of drawing on traditional material to make up new verses on the spot.

…Hwilum cyninges þegn

(…At whiles a thane of the king,)

guma gilphlæden / gidda gemyndig

(A man laden with rhetoric [gilp], mindful of stories [gidd],)

se ðe ealfela / ealdgesegena

(who of a great number of old legends)

worn gemunde / word oþer fand

(much remembered, word after word found,)

soðe gebunden / secg eft ongan

(truly bound; the man began)

sið Beowulfes / snyttrum styrian

(the adventure of Beowulf to skilfully stir up,)

ond on sped wrecan / spel gerade

(and speedily [or successfully, or handily] to recite an appropriate tale,)

wordum wrixlan / welhwylc gecwæð

(varying [or interweaving] his words; everything he told)

þæt he fram Sigemundes / secgan hyrde

(that he about Sigmund had heard said)

ellendædum / uncuþes fela

(of his valiant deeds; many unknown [i.e. to others])

Wælsinges gewin / wide siðas…

(battles of the Walsings; wide adventures….)

This well-versed thane (not necessarily the court scop, nor a harp-player on this occasion, as he is riding on horseback) then goes on to regale his fellows with the tales of Sigmund and Heremod, apparently comparing and contrasting them with the story of Beowulf. Since he does so in the course of a single journey on horseback, he has obviously had no time to prepare his song in advance, but he is laden with old legends and oratory and that is taken as sufficient explanation for his ability. The references to finding words, binding them truly, and speedily or successfully ‘reciting’ (not silently composing; the word used is wrecan, literally ‘to drive out’) all suggest the difficult feat of spontaneous composition.

In some ways the process described here resembles free improvization, not recomposition, but the majority of what the thane recites has to do with Sigmund and Heremod and yet he is putting this old material into the context of a new song. This could be interpreted as an acknowledgement of the preliterate scop’s ability to compose verses on traditional models in the heat of performance. As we have said, though, it may be a somewhat vague, garbled and unreliable memory, because it is doubtful that the Beowulf-poet was able to perform such a feat himself.

The Lyre, the Harp, and the Inkhorn

As we have already mentioned, the Old English scholar Francis Magoun wrote a number of articles in the 1950s in which he applied the oral theory to Anglo-Saxon poetry. These included an analysis of the formulas in the poems, an account of the Cædmon story, and a study of the ‘beasts of battle’ theme (the appearance of wolves, eagles and ravens before or during scenes of bloody slaughter) that occurs in many Old English poems. It will be useful to remember throughout this discussion that a formula is, by Parry’s definition, “a group of words which is regularly employed under the same metrical conditions to express a given essential idea”.8

On the basis of Magoun’s analysis as well as his own, Lord felt able to proclaim (in Singer of Tales, p.211) that “the formulaic character of the Old English Beowulf has been proved beyond any doubt” and that “this exhaustive analysis is sufficient in itself to prove that Beowulf was composed orally”. As we have seen, this assertion did not survive the scrutiny of other scholars, who pointed out that more obviously literary works in Old and Middle English are also filled with formulaic language. In his later works9, Lord ended up moderating his position, by admitting the possibility of a ‘transitional’ stage in which literate poets continue to use the oral-traditional style.

In the meantime, however, the oral theory had been brought into a degree of disrepute. Oral-theorist David Bynum, in the Preface to his Daemon in the Wood (pp.8-9)10, excoriated Magoun and his followers for misapplying Parry’s methods:

Oversimplification of the Parry Test [i.e. formula-counting analysis of twenty-five lines of a poem, first practiced by Parry upon the Iliad and Odyssey] leads to spurious results and needlessly confuses scholars who want to know what literary monuments of the past might be oral compositions. Such confusion has been felt most acutely in the field of Old English… The movement began with Francis P. Magoun’s paper on the “Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry” where magoun dutifully performed the convert-to-Oral-Theory’s initiatory ritual of the twenty-five-line Parry Test not just once but twice over. He did so, however, without regard to the vital distinction between epos and other kinds of poetry; from the outset he strove to bring into the compass of hypothetically oral traditional poetry the very genres that Parry had in the case of ancient Greek been obliged by his understanding of oral style specifically to exclude despite the considerable incidence in those genres of phrasal repetition, namely ‘lyrical-elegaic’ and ‘encomiastic’ (‘praise’) poetry, riddles, and such manifestly non-epic poems as Christ and Satan. Whereas Magoun diligently quoted Parry’s warning that “usefulness rather than mere repetition is what makes a formula”, he nevertheless made his twenty-five-line Parry Test of Beowulf without any preliminary consideration as to whether the fact of oral formula could be shown in Beowulf as though the chart itself were somehow proof of oral formulaic style, and innocently commented, “The formulaic character of the verse is demonstrated by Chart I…” …

Magoun’s mechanical imitation of Parry without regard to the controls Parry set upon his own procedure set a precedent for a whole generation of younger scholars to elaborate in the same vein. Soon there was hardly any poetry in Old English for which someone had not mooted oral origins, and always with as much reliance as possible on the merely mechanical part of the Parry Test…

Much of this comes across as a bit harsh, opposing the supposed bungling of Magoun11 to the “pristine and still correct” work of Parry, as if throwing a cargo-cultist out of the air-traffic-controllers’ union. One wonders if Bynum has really forgotten that Parry’s chief disciple, Lord, had by this time endorsed most of Magoun’s methodology in Singer of Tales. What Parry would have thought of it, we cannot know, owing to his untimely death in 1935 soon after his trips to Jugoslavia.

That said, Bynum is not exactly wrong. When Parry ran his formula-counting tests on samples of the Iliad and Odyssey (see this article), he had already published two French-language dissertations, containing exhaustive proof that the repeated phrases in Homer were dictated not by artistic choice but by metrical convenience.12 He had also distinguished this telltale sign of oral technique from the mere literary repetition (such as “pious Aeneas” in Virgil’s Aeneid), made for dramatic effect or in imitation of traditional style. Magoun made no attempt to replicate any of this preliminary analysis; he just starting counting repeated phrases, without seeking to penetrate the technique and psychology behind them. And as Bynum says, he lumped in with epic various lesser genres that one would expect to find traditionally memorized, not recomposed, because it is only the pressure of long narrative that precludes verbatim recital and gives rise to the recompositional technique.

We can hardly say on the basis of such flawed work that Beowulf was “composed orally”. And why, too, should we allow the oral theory to retreat into the halfway-house of the ‘transitional stage’ in which writers continue to compose in the oral style? We should admit the possibility that Lord, Magoun and their followers were hoodwinked by the pretensions of an archaizing literary tradition, somewhat analogous to the 18th-century ‘Augustan’ epic poesy of John Dryden and Alexander Pope.

The single most useful academic book that I have yet read on these questions is The Lyre and the Harp by Ann Chambers Watts. It begins (p.5) by acknowledging the fact that much of Parry’s methodology was lost in transition to the Old English field:

If one should study the work of Parry in Homeric studies, of Lord in studies of the Guslars, and then of Magoun and others in Old English poetry, it is at once apparent that Parry’s original thesis has suffered metamorphoses of detail in the transition from Greek and Serbo-Croatian to Old English. These metamorphoses have occurred largely without explanation or, when a discreet change is overtly acknowledged, the reasons for it have not been sufficiently explored.

After extensively summarizing first Parry’s work on Homer, then that of Magoun and his followers in Old English (like I said, this is a useful book if you can get hold of it, and can be bothered with its subject matter), Watts goes on to adduce many more ways in which Parry’s original methodology ‘metamorphosed’. One of the two most important differences (we’ll get to the other in a moment) is that the definition of a formula adopted by Magoun and others is much less rigorous than that of Parry. Whereas Parry had excluded short connecting phrases from his definition of a formula, Magoun (in his ‘beasts of battle’ article, pp.1-2) insisted on the formulaic importance of a word as insignificant as þa – which means simply ‘then’ or ‘when’.

The predictable result, as Watts (p.94) points out, was statistical inflation:

In this consideration of the formula both the Old English scholars’ silent deviation from Parry and the eventual magnitude of what may initially have seemed a trivial deviation have been pointed out. Magoun’s treatment of the formula absolutely determines his statistics [i.e. of formula density in Beowulf and other poems] (“70%”) and of course the statistics are his conclusion. ... If Magoun and his followers had selected a more consistent definition of the formula in Old English poetry, their statistics would undoubtedly have been less persuasively conclusive. Even by rigorous standards, such as those which Parry found workable in Homeric studies, there are numerous formulae and formulaic systems in Beowulf, Elene and other Old English poems; but Magoun and his school have somewhat tipped the scales by their looser methods of amassing evidence.

Watts proposes a reconsidered definition of the Old English formula: “a repeated phrase of a consistent metrical shape long enough to fill any one of Sievers’ five verse-types” (p.126). This means, above all, that such a phrase must be at least a half-line in length – and in the context of Old English poetry, this means that all formulas must consist at minimum length of short phrases with two strongly stressed syllables. This is a category to which goldwine gumena (‘gold-friend of men’) and Beowulf maþelode (‘Beowulf parleyed’) can be admitted, while single words and connectors like þa (‘then’ or ‘when’ ) are kept out.13

On the basis of her stricter definition, Watts proceeds to reanalyse the formula-counting statistics for samples of Beowulf and Elene compiled by Magoun, Lord and others, which supposedly proved “beyond doubt” that at least one of these poems was “composed orally”. And here are her results (from p.181 – note that the word ‘verse’ refers to a half-line, and that ‘underscored’ means ‘identified as a formula or part of a formulaic system’):

As you can see, once we start using reasonably strict definitions, the percentages for formula density in the text samples drop to 50% or lower. Watts concludes (p.182):

Compared with the burden of proof compiled with consistency and circumspection by Parry for the Homeric poems and by Lord for the Serbo-Croatian poems, the proof amassed by Magoun, Creed, Diamond, Nicholson and others less concerned is too thin, and especially too permissive, to enable Old English scholars to support the Parry-Lord thesis in Old English poetry as logically as it may be supported in Greek and Serbo-Croatian poetry. If statistics are arrived at by methods similar to Parry’s, statistics for the Old English poems themselves are simply not conclusive. The primary evidence is not enough from which to form a picture of the illiterate singer and the whole psychology of his composing in his oral art.

Of course, unlike those early oralist scholars named by Watts, we are not trying to defend the thesis that Anglo-Saxon poems were dictated to scribes by illiterate scops. We have accepted them as self-evident literary works, and are interested only in the degree to which their language echoes that of an underlying oral tradition. But we also want to know whether the meter and style of these poems can provide us with a template for the revival of preliterate poetic techniques in modern English. Even leaving aside the manifold difficulties of translatio studii that such a project would be sure to encounter, surely its foundation-stones cannot be laid upon on what may be nothing more than a traditionalist literary genre.

Given that no-one has yet proved of Old English formulas what Parry proved of Homeric ones, we cannot necessarily take the fact of formulaic language in these poems (which is obvious to anyone who has eyes to read them) to be evidence of oral composition in a literary mode. Does not Virgil’s Aeneid have its repeated formulas, such as “pious Aeneas”? For that matter, does not the epic poesy of Alexander Pope contain a great many repetitions and near-repetitions that could be interpreted as formulas14 – and yet are these formulas not English translations of Latin translations of orally-composed Greek originals, cast in a decadent literary style so restrictive as to make recomposition impractical?

We cannot, however, permit such a freefall into scepticism, because there is an obvious difference here. Virgil imitated Homer in Latin hexameters derived from Greek, and 18th-century Augustan poets imitated both Virgil and Homer in syllabic rhyming verse derived from French and Italian. But the Anglo-Saxon poets, in the grand scheme of things not long converted to literacy, were imitating the meter and language of their own ancestors. There is no real reason to doubt that their literary poetry grew up out of their oral poetry; the only question is to what extent they changed and refined what they had inherited from the past.

The Spendthrift Style

Besides the recounting of formulas, there is one other line of revision pursued by Watts that exposes big differences between Homeric and Anglo-Saxon poetry. It concerns not the number but the nature of the formulaic phrases found in the texts – which, as Bynum reminds us, Parry had extensively analysed for Homeric poetry long before he started sampling verses and counting repetitions. What Parry discovered by his analysis (in addition to many other things; we are simplifying here) was not just that Homer chose between equivalent phrases primarily on the grounds of metrical convenience, but also that he did so with maximum economy of expression. And to this economy Parry gave the name of thrift.

Thriftiness may or may not be characteristic of oral poetry in general; but one thing of which we can be certain is that it has no place at all in Old English poetry, the style of which would be better described by the term spendthriftiness.

For one thing, as Watts points out (pp.100-2), “neither Beowulf nor any other Old English poem contains epithets comparable to the Homeric type”. In Homer the epithet always comes with the name or noun for the person or thing (e.g. ‘swift-foot Achilles’, ‘wine-dark sea’), is never substituted for it, and is very rarely varied. In Old English, on the other hand, the dominant tendency is to drop the proper name and generic noun, and describe both people and things by a rotating selection of variable antonomastic expressions. In Beowulf, for example, the phrase eorla hleo (‘aegis of nobles’) is applied to kings Hrothgar and Hygelac as well as the young princeling Beowulf; and yet any one of these characters might be described anywhere else by other expressions suited to their general ‘category’ (e.g. goldwine gumena ‘gold-friend of men’ for kings, magoþegn modig ‘bold young thane’ for young heroes, hilderinc ‘battle-warrior’ for kings or heroes or even monsters).

As anyone knows who has read the original text of Beowulf, several of these expressions are often cycled through by the poet in the course of a cluster of lines. This constant variation and multiplicity is alien to the concept of thrift that Parry established for Homer.15 As Watts says (pp.103-4; all emphasis mine):

Variation, which [Arthur Gilchrist] Brodeur16 defined as “a double or multiple statement of the same concept or idea in different words with a more or less perceptible shift in stress”, is extremely rare in Homer, and is the sign of a grand difference in the spirit of Old English and Homeric styles which is far too complex for complete description here. Suffice it to say that where Homer selected or learned from a traditional stock a few epithets and phrases to belong to a few of his heroes and their surroundings for all time, for the duration of the “song”, so that he could proceed from a single statement of their actions, the Old English poet selected or learned many more adjectives or nominal expressions than he had heroes with which to match them, so that he could linger over the single idea of the name and the character through the device of multiple statement… The difference is thus what many have felt it to be, the difference between haste and leisure, action and descriptive meditation, complexity of incident and complexity of qualification.

…

A style that substantially depends upon variation is probably unlikely to evince the economy of the Homeric formulae in its repeated verses, since the whole direction of such a device is, mechanically speaking, towards superfluity. The artist, instead of persisting in the employment of a phrase which will satisfy all occasions of a certain metrical type, calls forth a great variety for one occasion, no matter its metrical type. Even though some of the phrases that contribute to Old English variation are demonstrably drawn from a traditional store of phrases, nonetheless many others are not formulaic; and all in all, it seems reasonable to conjecture that a compositional habit like variation would encourage individual inventiveness.

Now, the fact that Old English style depends upon variation does not necessarily mean that it cannot have been recompositional. It may simply reflect an oral-poetic system that works on different principles from the Homeric one, favouring a leisurely and allusive approach instead of a brisk and direct one. But if this were the case, we should expect to find it a complete system, fine-tuned to the solution of problems that universally arise when composition in performance is attempted. Since the most onerous of these is the risk of being caught at a loss for something to say, such a system should enable the scop to find a phrase for every occasion and an escape from every tight spot into which the demands of the meter might throw him.

It is often assumed prima facie that Old English poetic language was just such a system. People are fond of pointing out that it has many synonyms (such as rinc, secg, wiga, scealc and more for ‘man’ or ‘warrior’) and compound words (allusive kennings like ‘whale-road’ for ‘sea’ and ‘battle-light’ for ‘sword’, as well as more prosaic compounds such as ‘battle-warrior’), which serve to meet the demands of variation and circumlocution. But once we look more closely, we find the system as a whole very incomplete and uneven, tending towards redundancy in some areas and deficiency in others. Watts makes this point on pp.106-7 (summarizing William Whallon’s article “The Diction of Beowulf”, which can be read in full here):

Whallon’s persuasive illustrations are comparisons of the Greek and Old English expressions for “shield”, “ship”, “sea”, and two epic heroes, Odysseus and Beowulf... The figures vary, but throughout Whallon finds the Old English superabundant, having many too many expressions that in meter and alliteration are completely interchangeable, nor among them do all the possibilities of meter and alliteration begin to be represented… “The difference,” he remarks, “is decisive and vital: the language of Beowulf lacks the economy expected from a formulaic language that is highly developed.” … Speaking generally, Whallon observes that “some prosodic needs have two many solutions, some have none; a greater neatness, uniqueness and inevitability would appear desirable on the one hand, and a greater amplitude on the other.”

Whallon concludes from this that Beowulf represents “an earlier stage in the development of an oral poem than do the Iliad and the Odyssey” – but as Watts points out, this is hardly a compelling explanation of the evidence. Obviously it is Homer who has the (vastly) greater antiquity17, and even this becomes irrelevant when oral poetry is traced back to the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. It would be more reasonable to argue that Beowulf represents not only a much later stage in the life of an oral tradition, but also the postmortem preservation of that tradition in the glacial ice of literacy – which has caused some parts of its original structure to become distended while others have rotted away.

The aspect of the living oral tradition, in its full flush of health, has of course been lost to memory forever. But as long as we are prepared to separate that which belongs originally to the tradition from that which comes from the literate medium superimposed on it – blood from water, and flesh from ice – we can certainly make some less-than-wild guesses with the aid of the Homeric and South Slavic analogies. The most obvious place to start is at the level of the meter, which can be compared to the skeleton of a poetic style.

The Not-So-Long Line

The details of the books and articles on meter that I have slogged through in the course of my reading need not detain us here. For one thing, they are mostly dull as dishwater, and apt to snap the strained patience of my audience. But more to the point, they are overwhelmingly concerned with the theory of Eduard Sievers, which identified five basic rhythmical patterns or ‘types’ of half-line in Anglo-Saxon poetry.

These are best learned in modern English, through the mnemonic given in Part XI of Paul Deane’s Field Guide to Alliterative Verse18, with special attention to stressed (‘DUM’), half-stressed (‘Dah’) and unstressed (‘duh’) syllables:

Pride and anger (DUM-duh-DUM-duh – Type A)

brought pain and loss (duh-DUM-duh-DUM – Type B)

and hate festered; (duh-DUM-DUM-duh – Type C)

Hell’s masterwork (DUM-DUM-duh-Dah – Type D)

overwhelmed all. (DUM-duh-Dah-DUM – Type E)

Because the unstressed syllables in this meter are somewhat variable, Sieversian scansion soon becomes larded with complications as more and more sub-types are identified and rationalized into the system. This cannot but provoke our scepticism as to whether such a variegated meter really reflects an underlying oral tradition, since even the five basic types make for more complexity than the Serbo-Croatian decasyllable (which consists of just two half-line types, an opening four-syllable pattern and a closing six-syllable one). But I doubt that even the full gamut of Sievers types surpasses the complexity of the Homeric hexameter line, with its variable formula lengths and restrictive patterns of dactyls, spondees and trochees.19

Overall I am inclined to suspect that Sievers merely discovered some general underlying patterns, which may never have entered the conscious awareness of oral scops or even literate poets.20 But even if it were proven to be otherwise, the types would not present any real problem for our argument. The same cannot be said for the second important feature of Anglo-Saxon meter – that is, what we at Anamnesia call chyme, but almost everyone else refers to as alliteration.21

As the deliberate misspelling suggests, chyme is simply an alternative form of rhyme, which works by matching the initial sounds in stressed syllables (as in, for example, fair and foul.) While end-rhyme is used to link lines together in couplets or quatrains, the function of chyme in Old English verse is to link two half-lines containing two stressed syllables each into a full line containing four stressed syllables. The ins and outs of this verse-style have been laid out at length in a previous post, from which we shall quote only the most relevant part here:

Third, there is a traditional rule for placement of chyme, which I shall try to express as succintly as possible: either the first or second stress (or both) in each line must chyme with the third stress, but the fourth stress must not chyme with the third. This allows for a range of legitimate patterns:

The Everlasting Ruler wrought a beginning (ABBC)

Heaven as a roof – the Holy Maker – (ABAC)

Land for the living – the Lord Almighty (AAAB)

The fourth stress is thus deliberately omitted from the chyme scheme, and is only brought back into it in the patterns ABBA (e.g. “The Everlasting Ruler wrought an end”) and ABAB (e.g. “Heaven as a roof, the Holy Ruler”). The pattern AAAA (e.g. “Land for the living, the Lord of Love”) is considered to be overegging the pudding, but it does sometimes rear its head in Middle English texts.

Remember that these rules seem much more onerous to modern Anglophones than they would have seemed to Anglo-Saxons, who enjoyed not only a word-hoard of traditional phrases but also a freer word-order. All the same, they are quite strict, and to botch or drop the chyme is to break the meter – something that is technically known as structural ornamentation, and found neither in the works of Homer nor in South Slavic oral epic (nor, to my admittedly anaemic knowledge, in Sanskrit epic). Since structural ornamentation is much more common in later literary poetry (case in point, the rhyming epics of Dryden and Pope) and memorial traditions (such as the Anglo-Scottish ballads collected by Francis James Child), its presence in Old English verse might be ‘suspect’ from our point of view. This is all the more so on account of the fact that it is, above all, obligatory chyme that enforces the Old English variation and circumlocution that so contrasts with the style of Homer.

Indeed, one does not need the help of a statistician to look at the chyme scheme of Beowulf and find some pretty compelling evidence against its oral composition. That the chyme is almost never broken might conceivably be put down to scribal correction, but there are some stylistic clues as well. Despite the frequent use of thrice-chyming lines (i.e. AAAB lines, like “Land for the living, the Lord Almighty”), which invariably narrow down the available diction for the second half of the line, the narrative trips along without much visible recourse to ‘filler’ in these places. And although some of the chyme rules are very strict – for example, words chyming on st- are only chymed with each other, and never with others that chyme on s-, sm-, sp-, etc. – they do not impede the flow of thrice-chyming lines.

See, for example, lines 926 and 1409:

stod on stapole, geseah steapne hrof

([he] stood upon the steps, saw the steep roof])

steap stanhliðo, stige nearwe

(the steep stone-cliffs, the straitened paths)

The choice of diction in the second halves of these lines must have been extremely constrained, and one wonders if a recompositionist poet would not have either loosened the rule concerning st-sounds or instinctively avoided doubling them in the first half of the line. That none of the oral theorists and critics of the theory that I have so far consulted have seen fit to comment on this (if only to dismiss it) seems baffling; but then, in all likelihood, none of them have tried picking up a lyre in their lives. Once I did so (more on this later), I soon learned that double chyme in the first half-line makes for double constraint in the second, and that underused sounds are bound to present problems unless they can be assimilated to more versatile ones.

Of course, some might object that such practical experimentation can only be misleading, because we modern amateurs cannot know what would be hard or impossible for a skilled recompositionist. Yet there is a clear analogy between strict chyme (a.k.a. front-rhyme) in Old English and consistent end-rhyme in Serbo-Croatian, given that both are examples of structural ornamentation. It is not exactly hard to rhyme in Serbo-Croatian (at least relative to English), and some of the fixed formulas cited in Singer of Tales (pp.59-60) take the form of rhyming couplets; yet the oral poems are generally unrhymed, and consistent rhyming seems to be sufficiently difficult for the guslars as to require writing or verbatim memorization.22

This is illustrated in an interesting tidbit buried in Parry’s unfinished book on South Slavic poetry (published by his son Adam Parry in The Making Of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry; see p.442):

When I asked him [i.e. Nikola Vujnović, a young guslar and assistant of Parry] to recite the poem from the beginning he was able to do so only for twelve verses, and then lost himself in making the rhymes (doubtless had he been playing the gusle he would have had time to think of his verses as he sang or played the gusle between the verses). His explanation which, in its way, is doubtless true, was that it is very easy to forget poems that are rhymed. With this should be compared the statement which he made a week ago at Novi Pazar when Đemail Zogić [another guslar] remarked that no two singers ever sing the same songs alike. He then stated that the one exception was with rhymed poems. All this means that the song without rhyme heard in the manner habitual to the traditional poetry is recreated by each singer in his own verses more or less as an improvisation each time. The poem in rhyme, however, must be learned by heart, and when forgotten it cannot be re-improvised on the instant, since the rhymes present too great an obstacle to such improvisation.23 Corroborating this is Milovan [Vojičić?]'s statement of last year that one could not improvise in rhyme to the gusle but must have the time provided by writing materials if he would compose a rhymed poem.

Accordingly, in his posthumously published book The Singer Resumes the Tale (pp.347-359; the relevant chapter can be read here), Lord examines the pseudo-traditional epics of Andrija Kačić and highlights their consistent end-rhyme as the most salient telltale sign of literary composition. He then goes on (p.355) to muse briefly on the application to medieval Germanic poetry:

I do not know whether consistent rhyming is characteristic of written literature in all cultures; each case should be studied in its own context and history. I am thinking especially, of course, of the Nibelungenlied. Anglo-Saxon verse and the Old Norse Eddic poetry, the oldest Germanic poetries we have, do not have rhyme [note that there is a ‘Rhyming Poem’ in Anglo-Saxon and apparently one called “Ho̧fuðlausn” in Old Norse too, but these are exceptions and Lord’s statement is true of the rule]. If the Middle High German Nibelungenlied's rhyming comes from literary influence, where does that influence come from? As I have said, the South Slavic case is clear. Italian influence in the early sixteenth century…was applied to the epic decasyllable both by Filip Grabovac and by Kačić...

Arguably, though, what is truly decisive in this is not so much foreign literary influence as the literary medium itself. And what that medium tends to promote (if only by abolishing certain natural constraints upon oral poets) is not so much end-rhyme as structural ornamentation in general, including chyme. One imagines that ornamentational techniques long previously considered desirable, yet employed less than consistently by oral poets, would have been raised to obligatory status as a result of the new freedom to compose at leisure with pen in hand.24

What this suggests to us is that the Germanic oral tradition that preceded and underpinned the Anglo-Saxon literary poems may well have chymed, or alliterated, but perhaps did not always do so according to the strict rules worked out for ‘classical’ texts like Beowulf.25 And there is, indeed, some evidence to back this up.

It is well enough known that an early example of the ‘alliterative long line’ appears in an early 5th-century Proto-Norse runic inscription on the Golden Horns of Gallehus, which reads as follows:

Ek Hlewagastiz Holtijaz horna tawido

(I, Hlewagastiz Holtijaz, the horn made)

This of course presents no problem for our theory; had the long line not been considered desirable or even optimal in the heyday of the oral tradition, it would not have hardened into a structural feature of later literary poetry. But as Bernard Mees shows in his article “Before Beowulf: On the Proto-History of Old Germanic Verse” (downloadable with registration here), there are many other runic inscriptions of greater or lesser antiquity that tell a different metrical story. Almost all display some sort of chyme – which hints at the importance of this feature in Germanic oral tradition – but very few obey the ‘classical’ rules. For example, the inscription on the Kjølevik stone in Norway (probably also from the fifth century) is an AABB line that nonetheless strangely resembles the Gallehus one:

Ek Hagustaldaz hlawido magu minino

(I, Hagustaldaz, inhumed my selfsame son)

There are other inscriptions discussed by Mees that contain only three stresses per line, drop the chyme in some lines, chyme ABBB, etc.

It would certainly be wrong to assume that these ‘irregularities’ (which are not necessarily any such thing) had been purged out of Old English by the time the Anglo-Saxons were converted to literacy. They are quite present in some of the texts, but these tend to be dismissed as ‘corrupt’ or ‘degraded’, and excluded from the statistical analyses that seek to reduce Old English meter to regular principles. In “The Style of the Old English Metrical Charms”, Caroline Batten discusses some such examples, and makes short work of the notion that they represent low-quality verse.

The twelve metrical charms include, for example, the following ABCC lines:

Þis me to bote þære laþan lætbyrde

(This to me as a cure for the loathsome late-birth)

Þis me to bote þære swæran swærtbyrde

(This to me as a cure for the dreadful dark-birth)

Þis me to bote þære laðan lambyrde

(This to me as a cure for the loathsome lame-birth)

Evidently these are no mere slapdash lines: they are regular in their own way, repeating the initial phrase three times, and using chyme to showcase the formulas in the second half-lines (and, one imagines, to hold them in memory).26

Finally, we might mention Layamon’s Brut, which was written a couple of centuries after the Norman Conquest and straddles the transition point between Old and Middle English. This Arthurian literary epic, which has no claim to orality whatsoever (because Layamon says at the beginning that he compiled it from “three books thwacked into one”) is basically written in chyming verse, but contains all sorts of ‘irregularities’: half-lines linked by end-rhyme, lines that chyme on the fourth stress or on unstressed syllables or in odd patterns like AABB, as well as some lines that seem to contain no structural ornamentation at all. Again, its style has been called ‘degraded’ relative to what came before and after it – and from what I have read of it, I would be the first to admit that it does not come up to the standard of Beowulf and that its author was more journeyman than master.

But from which standard did Layamon’s style ‘degrade’? Not necessarily that of the English oral tradition – which may have survived long after the Norman Conquest among illiterates and ordinary people – but certainly that of the refined Anglo-Saxon literary tradition characterized by Sievers types and strict chyme. There is an obvious historical context for this loss of the ‘classical’ style27: the Great Replacement of the Anglo-Saxon nobility by a French-speaking Norman elite, which reduced the English language to subordinate status. One imagines that any native art forms patronized by the old nobility would have either disappeared altogether or collapsed into the culture of the subject people, much like the dispossessed nobles themselves. What I am hinting at here is the possibility that Layamon’s style, while perhaps corrupt and degraded in some ways (and certainly influenced by the conquerors, hence the end-rhyming and Arthurian content), may in other ways be closer to the loose style of the inscriptions and charms than is the style of the Beowulf-poet.

At the end of the day, though, we must bear in mind the error made by Magoun in extending his scope too widely into non-epic genres. To the extent that we are pursuing the recompositional tradition of the Anglo-Saxons (if there ever was such a thing), we are after the specific meters and styles of narrative epic, and cannot be diverted for too long by any old scrap of poetry that happens to be written in a Germanic language. It would be hard to argue against the close association of epic with the ‘long line’; all that we are saying here is that it may have been employed more loosely in oral poetry than in the derivative literary tradition.

Inconclusion

I did warn you in advance that we are asking questions whose answers were long ago forgotten, and that none of our lines of inquiry can lead us all the way through the void of this collective forgetting. But now that we have duly trudged the traceable paths, and illuminated what little we can, we should be able to make some shots into the darkness and stand a good chance of grazing our quarry.

First, it seems reasonable to assume that the Anglo-Saxons (or at least, their continental Germanic ancestors) had a recompositional poetic tradition comparable to that of Homer and the guslars at some time in their history. Widsith, Deor and Beowulf hark back to a more or less distant past in which scops sang heroic tales to the lyre, and the passage in Beowulf that goes into most detail on this seems to describe a process of spontaneous composition and creative reuse of old material. What we cannot know is whether that tradition had devolved (or, if you like, evolved) into a memorial one characterized by shorter poems and verbatim recital at some time before the conversion to literacy.

Second, there is no defending the speculations of early oral-theorists on the composition of Beowulf and other Anglo-Saxon poems. They are self-evident literary works, and representative of a literary tradition that deviates in some ways from oral composition. That said, the meter and poetic language of this tradition – unlike the later iambic-pentameter one that was pioneered by Chaucer, and reached its decadence in the hands of the Augustans– grew up directly out of the preliterate English oral tradition and retained many of its characteristics. We cannot know whether the varied, roundabout style was one of these oral residues or a later literary development, but the fact that it differs from Homeric style does not necessarily count against its antiquity; it seems that the complexity of Greek hexameter developed out of a simpler Proto-Indo-European meter28, so perhaps Germanic tradition took a rival turn towards complexity at the level of style and expression.

One relatively clear example of an oral residue is the formulaic language of the texts. Although some compound-words believed to be hoary traditional kennings may in fact be individual inventions, it seems reasonable to assume that formulas used in different poems throughout the entire corpus (such as goldwine gumena ‘gold-friend of men’, dreamum bedæled ‘bereft of joys’, heofones hwealf ‘the arch of heaven’, etc.) belonged to a common stock, and that the persistance of archaic language in many of them (for example, guma ‘man’ is too hoary to be used prosaically) points to inheritance from the preliterate era. One thing that we notice about many of these traditional phrases is that they chyme, or alliterate, which points to the ancient importance of this feature in embellishing the formulas and binding them in memory.

Third, and last, the importance of chyme to the oral tradition does not licence us to assume that it was governed by the strict ‘classical’ rules found in most of the texts. In light of the analogy with distantly related oral poetries, as well as the fact of human fallibility, it seems likely that the preliterate scop used chyme more loosely and inconsistently than did the author of Beowulf. Against this we should weigh the possibility that the long line was especially honoured and associated with epic (why else would it have become a structural feature of a literary tradition characterized by heroic language and narrative themes?29), and that the variant styles seen in the runic inscriptions and metrical charms were accorded a lower status. This would make the long line somewhat analogous to the Greek hexameter and South Slavic decasyllable, which were masculine epic meters differentiated by greater length and difficulty from the meters of lyrical and female poetry.

Postcript: The Way of Practice

The point of Anamnesia is to ‘unforget’ the art of traditional poetry, and it would be deluded to think that this could ever be accomplished by any amount of reading and interpretation of academic works. It demands creative effort, imaginative fooling and wising, as well as some unavoidable accommodations to modern language and culture. Even if we could access the luminar in Jünger’s Eumeswil, and call up an Anglo-Saxon scop to sing and harp for us, we would be able to make of him no more than an inspiration for the ‘recomposition’ of our own technique.

But it is necessary to exhaust the cautious, scholarly lines of inquiry in order to clear the ground for a fourth and last one – the way of practice. The way of practice cannot tell us much about specific oral-poetic traditions of the past; but in seeking to establish the tradition of the future, it can acquaint us with the universal human potentialities that underpin such traditions at all times. This will be the subject of later posts, but I would say a few words here about my experimentation thus far.

Some time before reading Lord’s Singer of Tales, which introduced me to the oral theory, I had already begun to produce and memorize rough translations of Beowulf and other Anglo-Saxon poems in the chyming verse meter. These were never written down, but rather temporarily recorded on audio and committed to memory. After reading Lord, and coming to know the difference between the recomposing poet and the text-memorizing jongleur, I ceased this exercise – by which point I had memorized about 2000 lines of Beowulf in addition to the shorter poems Wanderer, Seafarer and Deor. Although I can no longer recite these verbatim, because I have not been refreshing my memory by frequent recital, it is likely that the effort to memorize hundreds of lines of chyming verse served to fix the meter and phrasing in my mind.

Since then I have switched to a different exercise: revising my verse translation of Beowulf in an ‘autistically literal’ written form, making no attempt to memorize it verbatim, and periodically recomposing randomly-chosen sections of the poem with my own phrasing and embellishment. I have worked out a technique for doing this to musical accompaniment without dividing one’s attention (to be revealed in a later post), and have experimented a little with free improvization, which is of course a lot harder. Although I am still no good at any of this – and may yet discover something that once again throws up in the air all that has finally begun to coalesce – I can say a few things from practical experience that dovetail with what we have derived from interpretation of the evidence.

First and foremost, once you adopt a looser attitude to it (regulating unstressed syllables by ear, and matching underused sounds like th- and ch- with more versatile ones like t- and k-30), it becomes far from impractical to compose on the spot in chyming verse. That does not make it easy, and it must be admitted that it is harder to chyme in New English than it would have been in Old English, because far fewer words in our mongrelized modern tongue are stressed on their initial syllables. But even today, chyme seems more natural to English than end-rhyme, and more conducive to the ‘adding style’ described by Parry in which the poet builds verses by adding one phrase at a time.

As practice makes less imperfect, one begins to pick up certain tricks and techniques for overcoming difficulties. As we have mentioned, thrice-chyming AAAB lines should not be overused, because thus can lead to excessive constraint upon the singer and a monotonous effect on the listener. Note also that the placement of phrases containing two strong stresses is totally free in the first half of each line, and only constrained by chyme rules in the second, so it is quite natural to drive the narrative in the first half of each line while embellishing it in the second. The stark and terse style enforced by the four-stressed meter does not exactly suffer from such embellishment, and even meaningless filler phrases (‘you may well believe’, ‘I can tell you now’, and so on) are useful for slowing down the flow of verses and keeping the listener from getting lost. The variable, circumlocutory style of expression is also useful for this purpose (which leads me to suspect that it originated in the Anglo-Saxon oral tradition and not in the literary one derived from it). But the singer himself must learn to be patient, and not run where he could stride – lest he trip.

And yet, even when you are striding on ground well trodden (that is to say, recomposing instead of freely improvizing, which is like walking on ice or in darkness), every now and again something will come up that presents a genuine obstacle. At such points, above all you do not want to trip (fumble your words) or stop (be struck dumb); so the best option is to jump31, by bending the meter at the level of the chyme rules without breaking it at the level of the four-stress pattern (which is easy enough to keep up, and much more fundamental). This entails either chyming in an unconventional pattern, such as AABA or ABCA or ABCC, or else dropping the chyme altogether for one or two lines. Of course, one imagines that a true virtuoso would be able to keep up a narrative in chyming verse without resorting to any jumps; but even in a flourishing recompositionist tradition, most poets are not virtuosos, and the structural requirement of fully consistent ornamentation seems to me as foreign to oral poetry as verbatim recital.32

The thought has of course crossed my mind (and might well be defended from the vantage point of the evidence) that chyme belongs solely at the level of the formula, and that all loose or strict ornamentational rules governing the whole line are literary accretions that ought to be dumped. Accordingly, I have experimented once or twice with recomposition and improvization in blank accentual tetrameter, which superficially better resembles the unornamented style of Homer or the guslars. But the resemblance is, I think, deceptive; the rhythm of the English meter with its variable unstressed syllables is much less demanding, and to loosen the pressures of chyme to the point of removing them altogether would be to go from an excessively taut meter to an excessively slack one. It would come far too close to free verse, the style so beloved of those who want to abolish the metrical constraints that distinguish poetic language from ordinary speech.

Thus, on the basis of research and experimentation that is still ongoing, I can offer a qualified endorsement of chyming verse to any who might wish to follow me in my poetic quixotism. (And if it turns out in the end that this style is unsuitable, and must devolve into accentual tetrameter with optional chyme, then so be it; it is easier to step down from ornamentation to blank verse than to move in the opposite direction.)

This should hopefully amount to all we have to say on the metrical side of things. But in order to exhaust this topic, we have said much less than necessary on the higher levels of oral-poetic composition – that is to say, the themes and type-scenes and story-patterns. And then there’s musical technique, which might be useful even to those who have no especial yen for recomposition and narrative epic. If you’re at all interested in any of this, you might want to stay tuned.

All JSTOR links cited here are free to read, but require email registration.

In Homer’s Traditional Art, p.xiii – a book well worth reading for anyone more interested in the themes and type-scenes.

One example of such a memorial tradition would be the Anglo-Scottish ballad tradition sampled by Francis James Child, which may stretch back to the memorizing jongleurs of the Middle Ages.

Opland’s reasoning is that Xhosa-Zulu society, with its eulogistic poets attached to the retinues of kings and warlords, is (or recently was) more closely analogous to the society of the Anglo-Saxons than was the precommunist South Slavic society visited by Parry. That may or may not be so (he hardly says enough to prove it beyond doubt), but in any case a poetic tradition is not just an epiphenomenon of the social role of a bardic class. It is also an extension of a linguistic tradition, which in turn encapsulates a cultural tradition; and while many aspects of Old English and Serbo-Croatian can be traced to their common roots in Proto-Indo-European, no-one would say (for instance) that Old English must have resembled Classical Chinese, because of certain social similarities between the Heptarchy and the Warring States.

This does not mean that there are no real similarities. The Anglo-Saxons knew a tradition called the beot or gilp, traditionally associated with kings and warriors: it is often wrongly translated as a ‘boast’, but is more like a ‘pledge’ to do some brave or generous deed, probably made in poetized speech (which presumably would have been either memorized or improvized, delivered standing up, unaccompanied by music, etc.). It is this ritual ‘self-eulogy’ that best resembles Xhosa and Zulu izibongo, with its aggressive haranguing style and association with chieftains and battlefields. One imagines that important personages, such as kings, might have ‘outsourced’ this role (and other related ones, such as the recital of genealogies) to specialized individuals – and this might shed some light on the mysterious role of the þyle, or ‘royal orator’, the office of the Unferth character in Beowulf who criticizes the protagonist for his deeds while praising one of his rivals.

But the Anglo-Saxons quite clearly had another, partially-overlapping tradition in which seated poets sang heroic tales to musical accompaniment, which best resembles that of the South Slavic guslar and can be legitimately analogized to it. And the problem with Opland’s book is that more often than not, when confronted with direct evidence of this second tradition, he veers off the straight path of reasoning and into the African bush to pursue some trace or shade of an analogy with izibongo. To give you only the first of many, many examples, on page 42 he addresses the Germania of Tacitus, and says the following:

In the second chapter Tacitus tells us that “in ancient songs/poems, the only kind of history among them (‘carminibus antiquis, quod unum apud illos memoriae et annalium genus est’), they [i.e. the Germans] celebrate Tuisto, a god born from the earth, and his son Mannus as the founders of their people.” Carmen was used to refer to both poetry and song; with no reference to the performer or the performance, we cannot determine whether these celebrations, carminibus antiquis, were chanted or sung, whether they were poems or songs. That they were ancient seems to suggest that they were traditional.

But after musing a bit on whether these are poems or songs, narrative or non-narrative, entertainment or ritual, and admitting that Tacitus’s words are “susceptible of various interpretations”, Opland decides that “one reasonable solution seems to me to place these performances within the context of a eulogistic tradition, a tradition like that currently postulated for the primitive Indo-European peoples and current among the contemporary Zulu.” He then goes on to interpret them entirely with reference to izibongo, before ending his discussion with the following:

It is likely, too, that we are to postulate a eulogistic context for the poems (or songs) about the hero Arminius of the Cherusci that Tacitus says are still performed among the Germans (“caniturque adhuc barbarus apud gentis”, Annals…II, 88), though these may equally well be narrative Heldenlieder [i.e. heroic tales; emphasis mine].

But Opland declines to pursue this (rather likely!) possibility. Had he done so, he might have brought in the testimony of lines 88-98 of Beowulf (partly mentioned in the main text), which describe a scop playing a harp in a hall and singing a story of man’s beginnings long ago. Although this tale turns out to be the creation story in Genesis (as one would expect in this Christianized poem), if the theme was seen as a typical one for a harp-playing Germanic entertainer, then there are obvious parallels with what Tacitus says of the carmina relating the origins of men through the primeval figure of Tuisto. But Opland is too fixated on the izibongo analogy even to notice them.

He does this sort of thing rather a lot in his book, either denying the evidence for the Heldenlied-tradition, or else downplaying its importance and antiquity (although, to be fair, he lays out the evidence honestly and often admits that it can be read a different way). It gets quite frustrating to watch him wave away clear evidence of tale-singing poetry in the sources with references to the eulogising ‘tribal poet’, whom he has extracted mostly from speculation on Indo-European sacred kingship (specifically in his second chapter, pp.28-39) – that is to say, the very mists of Aryan prehistory wandered by us poor benighted souls who would sooner compare English traditions to Slavic than to Bantu ones. This review, in my opinion, does not go nearly far enough in its criticisms.

See Ruth Finnegan, Oral Poetry, for some examples, mixed with some criticism of the early oral theorists for concentrating exclusively on recomposition and failing to give proper place to memorial traditions. Lord harshly criticized memorizing performers in Singer of Tales (p.147), but he was referring to what might be called jongleurism or rhapsodism – a kind of performance art in which a literate singer memorizes a text verbatim and then recites it to an audience under the guise of a preliterate poet.

In “Vedas and Upanisads” (in The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, Gavin Flood ed., pp.68-98), Michael Witzel has this to say of the Rig-Veda tradition:

The Vedic texts were orally composed and transmitted, without the use of script, in an unbroken line of transmission from teacher to student that was formalized early on. This ensured an impeccable textual transmission superior to the classical texts of other cultures: it is, in fact, something like a tape-recording of ca. 1500-500 BCE. Not just the actual words, but even the long-lost musical (tonal) accent (as in old Greek or in Japanese) has been preserved up to the present.

Witzel does not clarify whether by ‘orally-composed’ he means memorized or recomposed or improvized; but one imagines that the Vedic poets must have constructed their verses in memory without the aid of writing and recited them, otherwise they could not possibly have repeated them often enough to drill them into the heads of the first memorizers. The fact that this tradition long predates the written Sanskrit heroic epics, Mahabharata and Ramayana (which seem more likely to have been dictated to scribes by recomposing poets, or recomposed by poets who had learned how to write) suggests that memorial poetry of a sacred character precedes recompositional narrative poetry and may be indispensible to its natural development. I would be grateful for any further information on this tradition from those with knowledge of the Sanskrit language.

This is a mere hunch based mainly on what Bede does not say – that is, that Cædmon miraculously turned Scripture into verse in the heat of the moment, which one imagines would have been quite worthy of comment in a literate era.

On the othe hand, the definition of a theme is more varied, but Lord defines it (Singer of Tales, p.211) as “a structural unit that has a semantic essence but can never be divorced from its form, even if its form be somewhat variable and multiform”. Examples include the themes of feasting, journeying by sea, arming a hero, etc. As Lord points out, Magoun’s notion of the ‘beasts of battle theme’ rests on a laxer definition, which raises to the status of a theme what he calls the motif of association between certain animals and battle scenes.

Specifically, Epic Singers and Oral Tradition and The Singer Resumes the Tale, both available to read in full online.

Although Bynum prefaces Daemon in the Wood with criticisms of Magoun’s statistical methods, he does not go on to correct them; rather, he reminds us that Parry defined formulas not as mere repetitions but as expressions of essential ideas, and proceeds to identify a perennial ‘two trees’ theme that is traced through Bantu folklore, South Slavic oral poetry and several other unrelated traditions. It’s a pretty sui generis contribution to oral theory and I am still not sure how to interpret what it claims to find. But on the subject of the definition of a formula, although Parry did define it with reference to essential ideas, he also said that such ideas are easiest to identify in the case of repetitions. Doubtless his theory would not have seemed so compelling to so many people had it dwelt in the nebulous ideational realm that Bynum explores in his book.