Homer's Inner House

Traditional poetic themes in theory and practice

In his Preface to Plato (pp.93-4), which seeks to explain the dominance of poetry in ancient Greece and why it was opposed by philosophy, Eric Havelock probes the mind of the oral-traditional poet by the light of a metaphor:

Let us think of [Homer] therefore as a man living in a large house crowded with furniture, both necessary and elaborate. His task is to thread his way through the house, touching and feeling the furniture as he goes and reporting its shape and texture. He chooses a winding and leisurely route which shall in the course of a day's recital allow him to touch and handle most of what is in the house. The route that he picks will have its own design. This becomes his story... This house, these rooms, and the furniture he did not himself fashion: he must continually and affectionately recall them to us. But as he touches or handles he may do a little refurbishing, a little dusting off, and perhaps make small arrangements of his own… Such is the art of the encyclopedic minstrel, who as he reports also maintains the social and moral apparatus of an oral culture.

We can conceive of this house full of objects as an image of the memory cultivated by a poetic tradition.1

Let’s say that the various routes through the house, which sometimes lead off to different rooms and at other times crisscross each other, are the poet’s repertory of stories. These are best understood as logical chains of events, which demand memorization, but might be varied in performance by any number of lingerings and digressions and shortcuts.

The objects and items of furniture in the house, which can be approached and handled in different ways, are the themes known to the poet. These include type-scenes, conventional descriptions, event-patterns: sea-crossings, land-crossings, speeches, feasts, the arming of heroes, battles, similes, catalogues, etc. As we shall see, many of them are versatile enough to be turned to all sorts of uses.

Finally, the poet must recount his inner journey in the words of a specialized language, and these are the phrases that form the building-blocks of his poem. These are not memorized and recited verbatim, but rather extemporized in the moment of performance (or as we say here at Anamnesia, recomposed). Yet some might be repeated from memory, others molded on traditional models, and others yet innovated within the constraints of the meter – hence my use of the all-encompassing ‘phrase’ instead of the more reductive (and arguably pejorative) ‘formula’.

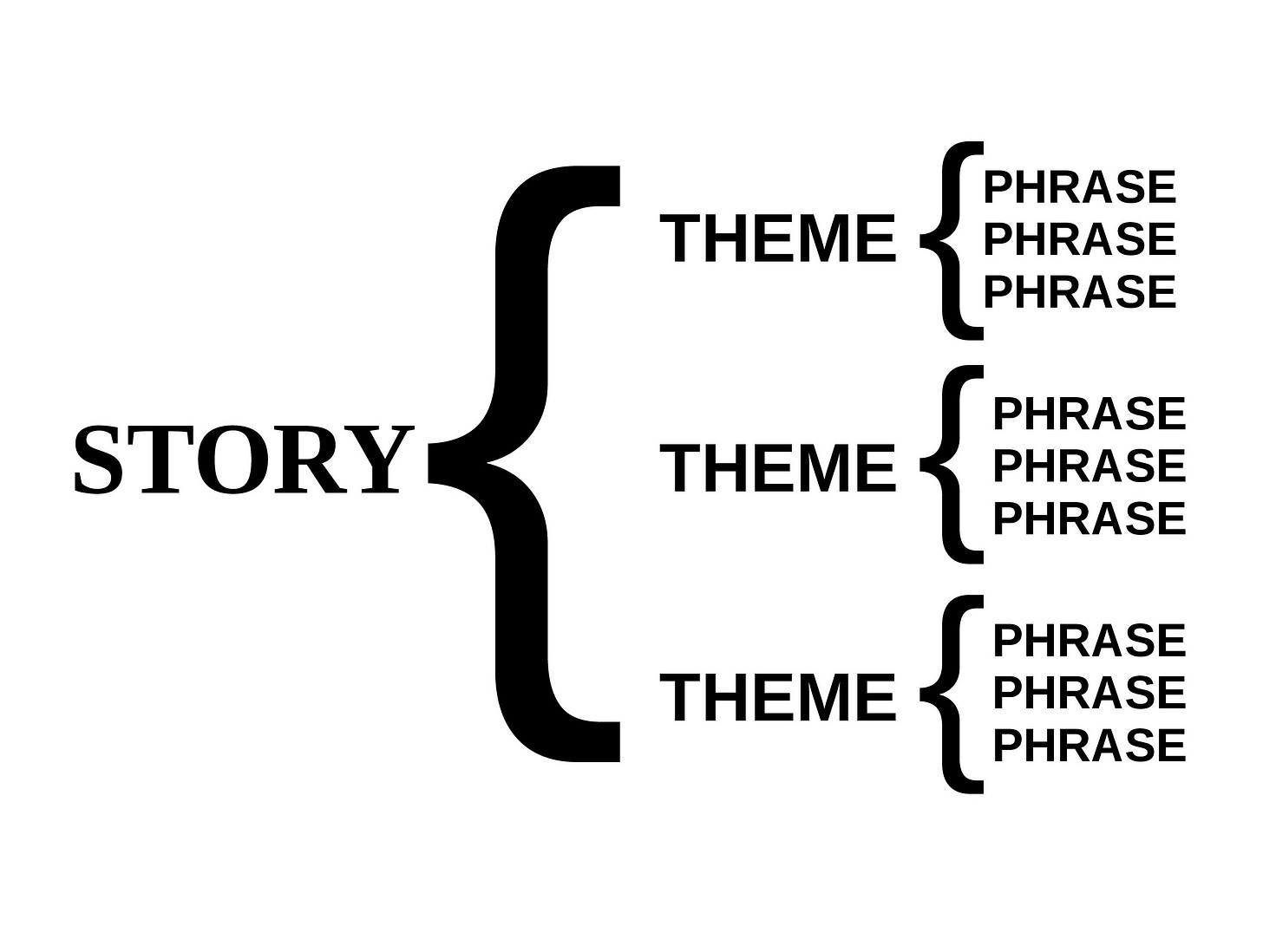

This structuring of a traditional epic poem at the three levels of story, theme and phrase can be illustrated more abstractly, like so:

(Bear in mind also that sub-levels can be identified between the three major ones, such as the merely ornamental motif that stands between the theme and the phrase. One example of this would be the appearance of certain animals – wolves, eagles and ravens – before or during scenes of violence in Old English poetry.)

Milman Parry founded the oral theory upon his analysis of Homer’s formulaic phrases, and most of the work produced by that school has continued to concentrate on this lowest verbal level of poetic composition. The oral-theorist starts with formulas and works his way up to the recurring patterns in themes and story-patterns (at least as long as he can avoid being dragged back down by academic controversies concerning the formulaic evidence). But this is opposite to the actual practice of traditional poets, who must begin with stories, and work down to themes and finally phrases in order to communicate them effectively.

Here at Anamnesia, we have also initially followed the way of the theorist, by concentrating primarily on meter and language. But as we begin to move from theory towards practice, we must move into the mental space of the poet, the ‘house’ that must be filled with ‘objects’ before we can invite others to visit it.

Anatomy of the Tale

Moreover, we must shift our focus to a different body of material, because the most useful academic work on themes is based on the Homeric poetry that was the original focus of Parry’s work. Although Old English poetry shows the influence of traditional themes – the sea-crossings and courtly scenes in Beowulf, the exile theme in the Wanderer, etc. – these are more truncated and vestigial than those found in Homer, and it is no wonder that they get conflated with mere ornamental motifs.2 Don’t take my word for it; let’s hear it from a scholar of Ancient Greek and Old English, namely Ann Chambers Watts (The Lyre and the Harp, pp.123-4; emphasis added):

Homer contains many exactly repeated clusters of formulae, line after line made to order for certain themes; but in Old English, where the longest repeated sequence of formulae is three verses, no such clusters occur even though certain themes have multiple appearances. Homer’s audience may entertain a security of expectation that when feasts are mentioned in the Odyssey the bread-baskets will be forthcoming, and the stools, and the red wine; or when a man is arming in the Iliad he will strap on his helmet before he takes up his shield. These and other minor acts, ornamental themes, of rising in the morning, arriving, departing, sailing, recur again and again in Homer and nearly always in the same wording and inner sequence… In Serbo-Croatian epic song also, according to Lord, formulae cluster about ornamental descriptions and are repeated in sequence nearly word for word. In Old English poetry, however, where ornamental themes recur with many echoes and parallels, phraseology is ever various. Though individual words may suggest or recall an earlier passage about a sea voyage or a battle, rarely is a single verse identical with one that went before. The famous sailings in Beowulf…share some vocabulary…but the variation on the very edges of similarity seems infinite.

In light of what we know about Old English poetry, this might be explained by the variation built into the meter, or by the greater distance of the Anglo-Saxon literary tradition from its underlying oral tradition. But these questions need not detain us.

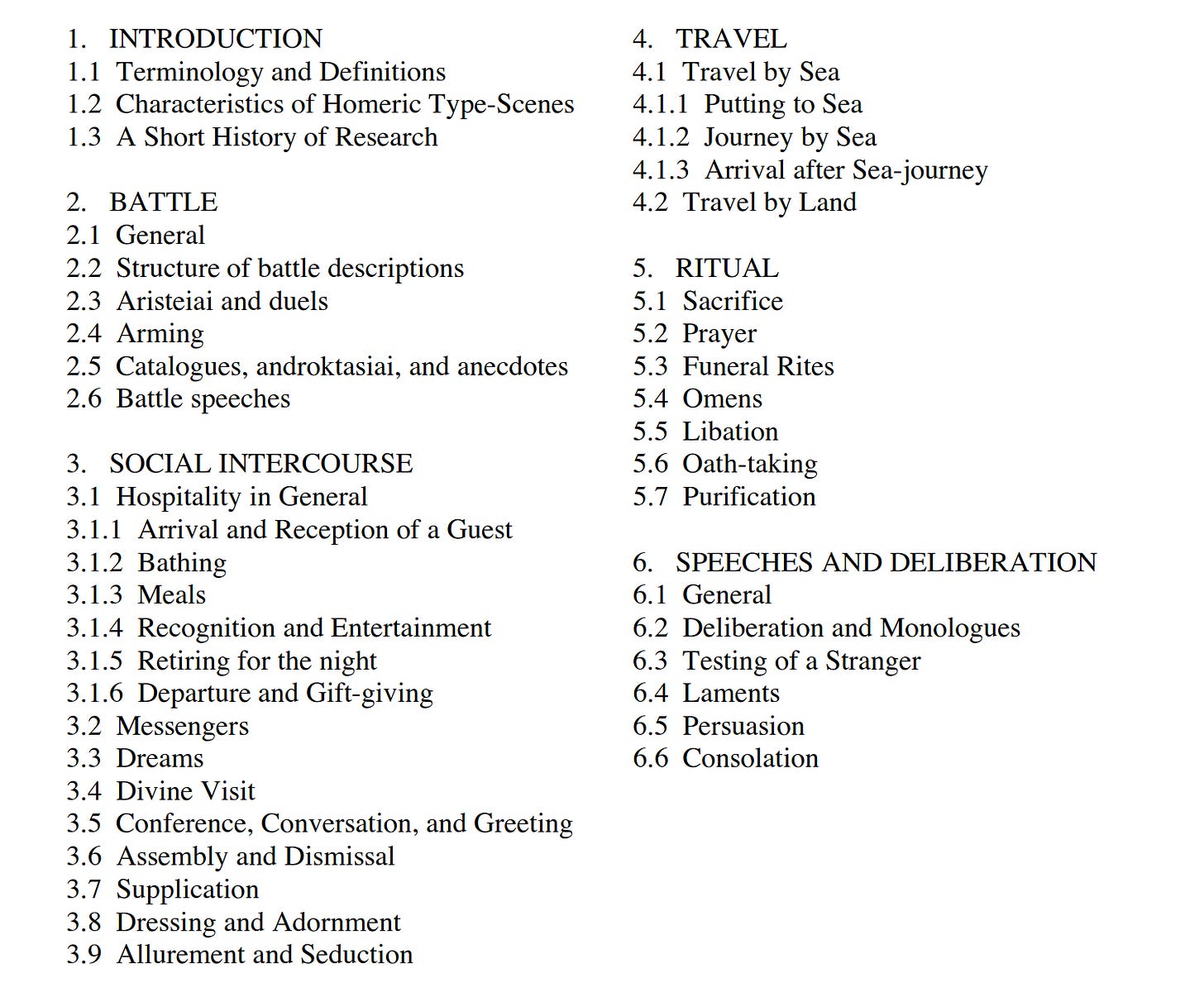

There are three ways to look at themes in Homer: by giving a broad overview, by tracing a single theme through various narrative manifestations, and by breaking down a section of narrative into its constituent themes. For the first option, we can consult Mark W. Edwards’s article on type-scenes in the journal Oral Tradition, which gives us some idea of the variety of the ‘furniture’ and ‘objects’ in Homer’s house:

As Edwards admits, this overview is by incomplete, as it deals solely with the sub-category of type-scenes. Descriptive passages are excluded, as are the long Homeric similes comparing characters to animals and natural forces. But much can be said about the collection of themes presented here.

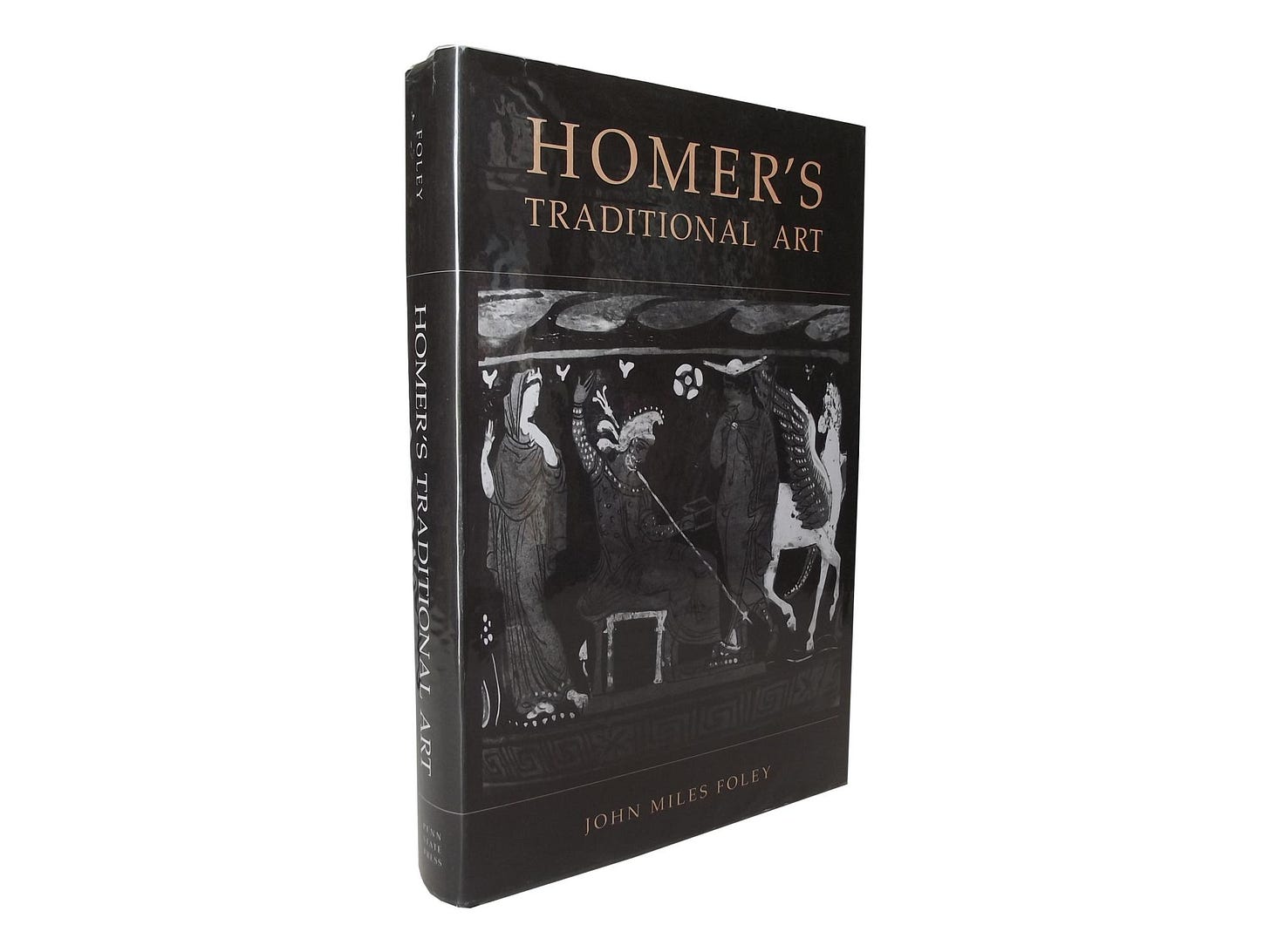

To home in on a single one, we must resort to a more detailed source: Homer’s Traditional Art by John Miles Foley, perhaps the single most useful oral-theory text that I have read on the subject of themes.

In Chapter 6 of this book (specifically pp.171-87), Foley discusses the Homeric theme of Feasting, which according to his count makes thirty-two appearances in the Odyssey and three more in the Iliad. He notes that each instance of the theme involves some shared features, such as a host and one or more guests, and often some repetition of phrases and imagery. There is also a deeper significance to the theme3 that lurks beneath it at all times and places:

Simply put, collation of the thirty-five instances of the Homeric Feast sign reveals that it betokens a ritualistic event leading from an obvious and pre-existing problem to an effort at mediation of that problem. The signal itself is protean: the initial disruption takes many different forms, the pattern itself is structurally quite flexible, and the outcome is quite unpredictable in its specifics. … But what typifies each and every Feast scene is at minimum the promise of improvement or remedy, and it is this hoped-for trajectory that provides a recurrent, expectable context for the many individual dramas played out over the course of the Odyssey and Iliad. [p. 174; emphasis in text]

Foley moves on (pp.175-87) to a detailed discussion of nine instances of the Feast theme in the Odyssey:

Telemachos hosts Athena-disguised as Mentes (Book 1), in which the problem is the absence of Odysseus from his wife Penelope and the behaviour of her suitors, and the solution is given by the advice of Athena;

Kalypso feasts Hermes and then Odysseus (Book 5), in which the problem is Odysseus’s captivity and the solution is the message brought by Hermes from Zeus ordering Kalypso to release him;

Polyphemos’s cannibal feast upon Odysseus’s men (Book 9), in which the traditional content of the theme is eerily distorted, and the solution to the problem is delayed until Odysseus can hatch a plan to escape;

Kirke feasts Odysseus (Book 10), in which the theme is interrupted because Odysseus refuses to eat until the sorceress has changed his men back from pigs;

Odysseus’s men offend the god Helios by eating his cattle (Book 12), in which the traditional expectations evoked by the theme are again subverted, because the result of the forbidden meal is the loss of Odysseus’s men at sea;

Telemachos hosts Odysseus-disguised-as-a-stranger (Book 17), in which Penelope is present and hears crucial information concerning Odysseus’s return;

Penelope and Odysseus’s shared meal (Book 23), which is part of their long-awaited reunion;

Odysseus shares a meal with his father Laertes (Book 24), which leads to the conclusion of the narrative.

Note that this list includes not only conventional instances of the theme, but also perverted ones, such as the cannibalism of Polyphemos and the forbidden feast upon the cattle of the sun god. In this tradition, it would seem, the subversion of a theme amounts to only one of its many possible mutations (something that might explain why the modern obsession with subversion tends to reduce variety of expression and increase its formularity and predictability).

Finally, and most importantly, let’s see how themes act within the structure of a narrative. The events of the first book of the Iliad can be summarized as follows:

The Achaeans besieging Troy have sacked a city and the king, Agamemnon, has taken as his war-prize the daughter of Chryses the priest. Her father comes to the camp to ransom her, but the king refuses, so the priest prays to Apollo and brings down a plague upon the host. The mightiest warrior Achilles calls a meeting, in which an augur explains that the plague will go on until the girl is given back. Agamemnon declares that he must be compensated. After a heated argument, he takes the girl allocated to Achilles, who furiously insults the king and vows to abstain from the war. After the aged Nestor fails to reconcile them, both men retire to their camps, and Agamemnon sends Odysseus to take the priest's daughter back to her father. Achilles allows the king's heralds to take his girl, then appeals to his divine mother Thetis, who promises to intercede for him with Zeus. Meanwhile, Chryses gets his daughter back and propitiates Apollo with a sacrifice, after which Odysseus returns to the host. Thetis goes to Olympus and extracts a promise from Zeus to turn the war in favour of the Trojans as long as Achilles remains absent. Hera criticizes him, but Zeus threatens to lay hands on her unless she minds her own business, and Hephaestus smooths things over with his mother. The gods banquet and retire to bed.

With some help from another useful article by Edwards, “Conventionality and Individuality in Iliad 1” (free to read with email registration), we can break this down into the following constituent themes:

Invocation to the Muse

Supplication (Chryses to Agamemnon)

Prayer (Chryses to Apollo)

Divine Visitation (Apollo descends on the Achaean host)

Summoning an Assembly (Achilles)

Assembly scene (in which Agamemnon and Achilles argue back and forth)

Pondering scene (Achilles ponders whether or not to kill Agamemnon)

Divine Visitation (Athena restrains Achilles)

Mediation scene (Nestor tries to reconcile the two with words of wisdom)

Dismissal of the Assembly

Departure by Ship (Odysseus leaves with Chryses’s daughter)

Purification and Sacrifice (the Achaean host performs a ritual expurgation)

Messenger and Guest scenes (Agamemnon’s heralds go to Achilles to take his captive girl)

Prayer, Supplication, and Divine Visitation (Achilles complains to his mother Thetis and extracts a promise from her to petition Zeus on his behalf)

Arrival by Ship, Giving a Gift, Sacrifice-Meal-Entertainment, Retiring for the Night, Departure and Journey by Ship, and Arrival by Ship (Odysseus returns Chryses’ daughter to her father, takes part in expurgatory rituals to Apollo and returns to the Achaean host)

Absent-but-Concerned scene (Achilles waits dejectedly by his ships)

Supplication scene (Thetis petitions Zeus on Mount Olympos)

Divine Assembly scene (Zeus and Hera argue)

Mediation and Greeting scenes (Hephaestus smooths things over with Hera)

Feast and Entertainment scene (the gods banquet)

Retiring for the Night (the gods retire to bed)

As Edwards shows, all of these themes recur elsewhere in Homer, in similar and different formal shapes and phrasal clothing. And as Havelock shows in his own overview of the same material (Preface to Plato, pp.64-84), at least some of them can be seen as playing a didactic as well as a narrative role, by memorializing the social, religious and technological order of archaic Greece.

An Alliterative Iliad

Thus far we have confined ourselves to summarizing the work of oral theorists on the thematic side of traditional poetry. But the problem with this work is that none of it can tell us how to practice the techniques that it studies. Knowing how Homer might have navigated his house full of precious objects does not make our own any less empty.

Yet there are many hints as to practice in the work of those who witnessed the last gasp of the South Slavic oral tradition in the 20th century. Lord in Singer of Tales (p.189 in the free online version) has this say about the way in which novice singers in that tradition learned how to make use of themes:

The beginner works out laboriously the themes of his first song. I know, because I have tried the experiment myself.4 Even as one is learning to build lines, one thinks through the story scene by scene, or theme by theme… Although he thinks of the theme [e.g. that of a council or assembly] as a unit, it can be broken down into smaller parts; the receipt of the letter, the summoning of the council, and so forth. Yet these are subsidiary to the larger theme. They will be useful perhaps in other contexts later on, but the singer learns them first for use in the specific council of the specific song, with the appropriate names of people and places and their characteristics. The names are attached in minor themes of calling the council, introducing speeches, in question and answer. All this the learner thinks through before he can be satisfied with his singing and before he can move on to the next larger theme.

And more (p.228; emphasis added):

Although the themes lead naturally from one to another to form a song which exists as a whole in the singer's mind with Aristotelian beginning, middle, and end, the units within this whole, the themes, have a semi-independent life of their own. The theme in oral poetry exists at one and the same time in and for itself and for the whole song. This can be said both for the theme in general and also for any individual singer's forms of it. His task is to adapt and adjust it to the particular song that he is re-creating. It does not have a single "pure" form either for the individual singer or for the tradition as a whole. Its form is ever changing in the singer's mind, because the theme is in reality protean; in the singer's mind it has many shapes, all the forms in which he has ever sung it, although his latest rendering of it will naturally be freshest in his mind. It is not a static entity, but a living, changing, adaptable artistic creation. Yet it exists for the sake of the song. And the shapes that it has taken in the past have been suitable for the song of the moment. In a traditional poem, therefore, there is a pull in two directions: one is toward the song being sung and the other is toward the previous uses of the same theme.

All of this information is quite useful for revivalists. What we can gather from it is that we must relearn two storytelling habits that have more or less vanished from the modern mind. One is the construction of stories theme by theme, and the other is the protean recycling of themes from story to story.

There is, nonetheless, still a black chasm dividing theory from practice, opened up before us by the total loss of oral-poetic themes from our cultural inheritance. And this means we cannot follow the path of the South Slavic youths encountered by Lord, who learned themes from the songs of their elders along with formulas and stories and all other components of a functioning poetic language.

Or can we? As long as the literary fossils of ancient and medieval poetic traditions can be translated into our own language and meter – because the repetition of language is a subordinate but still important part of the theme – surely there is no reason why we cannot learn from them in much the same way as the neophyte learns from the elder.

As Ann Chambers Watts has warned us – and as I have verified by experience – the Old English tradition with its vestigial traces of oral themes is somewhat disappointing as a source of material. Unfortunately, it is also the only one that I am even moderately competent to translate. But I have summoned up some of the chutzpah of Ezra Pound5, and ventured to turn the entire first book of the Iliad into English chyming verse6 despite my lack of Ancient Greek ability. (I hasten to add that this was a one-off experiment, and that the other books aren’t likely to follow anytime soon; truth be told, it has been a painstaking business of line-by-line reference to the original text as well as to multiple dictionaries and translations.)

The difference between relative closeness to oral poetry7 and relative distance from it is quite obvious. For example, there are many instances of feasting (or at least communal drinking) in Beowulf, usually sketched out impressionistically in a couple or more lines. But there is nothing like this detailed description of a feast following a ritual sacrifice, which takes place after Odysseus returns Chryses’ daughter to her father (in Edwards’ list, the Sacrifice-Meal-Entertainment theme, which as Foley says contains many lines exactly repeated elsewhere):

So Chryses prayed, and Apollo listened; And they prayed and then sprinkled all the salted barley Twixt the horns of the beeves; then bent their heads back And slit apart their throats; and skinned the carcasses And cut away the thighs, and cowled them in fat; And enfolded it doubly, and flesh spread on From the rest of the body – red-raw slivers. The old man burned them on billets of wood, And made flowing libations of the flambent* wine; And with five-pronged forks stood the flanking youths. When the thighs were cindered, they tasted the innards, And sliced up all the morsels, and on spits transfixed them, And roasted them with thoroughness; and took them off. When the labour was finished and the fest prepared, They feasted to the full, none found to be wanting. When they'd driven off their lust for drinking and eating, Boys brought the wine-bowls, brimming with liquid. First came libations; then they filled the cups; And the youth of the Achaeans, all that day, Sang splendid paeans to appease the god. They chanted out their praise of him in crystal voices, And the Farworker** hymned by them harked and rejoiced. (* a portmanteau of flaming and lambent; translates Greek αἶθοψ) (** an epithet of Apollo; translates Greek ἑκάεργος)

On the other hand, in the presentation of some themes there is more resemblance between the two styles. After the aforementioned feast, Odysseus and his men return by sea to the host encamped at Troy (the Departure-Journey-Arrival by Ship theme); this is how I have rendered it in translation:

When the rathe-born goddess, rosy-fingered Dawn, Appeared to them resplendent, they put to sea Towards the vast-spread camps of the Achaean host. The Farworker graced them with a favouring wind; And when they reared up the mast and unrolled the sailcloth, White and wide-spread, the wind outbillowed it, Filled full its belly. By the foreprow reft, The purple-purling waves pealed and bellowed As the fast-speeding keel went cleaving her way. When they came to the Achaeans in their camps broad-spread, They dragged upon the mainland the dark-tarred ship, To the sands of the seashore; and stretched beneath her The lengths of plankwood, propping her high. Then they scattered every way to their ships and camps.

Compare this with the account in Beowulf, fitt XXVIII, of the protagonist’s return from Denmark to his homeland by sea:

... He went aboard; Drove deep water, and the Danes' land left. A single sea-raiment stood at the mast, A rope-rigged sail. The shipwood rumbled. The wind upon the waves the water-skimmer* Swerved not from the journey; the sea-goer* fared Floating foamy-necked forth o'er the waves, Over currents of brine, the curvèd prow, Till they gained to the sight of the Gothish headlands, The well-known cliffs. The keel updrove Under lash of the wind, and on land stood still. ... The broad-bosomed boat he** bound to the sand With anchorage fast, lest the ocean's force The fair timbers should thrust from the shore. (* epithets for a ship) (** i.e. the harbour-guard, whose introduction is omitted here)

This, however, is one of the rare instances of a theme in Beowulf that is spun out in relative detail with near-exact repetitions of language (specifically, that describing the “foamy-necked” appearance of a boat as its prow cleaves apart the waves).

Finally, in order to guard against any creeping notion that themes in Homer are pressed out of the cookie cutter, let us look at the three very different instances of the Divine Visitation theme identified by Edwards. The first is the descent of Apollo with his plague-arrows in response to the prayer of his offended priest:

So Chryses prayed; and Apollo listened, And came striding from Olympos with his shining bow And quiver o'er his shoulders – clashing as he marched And rattling with arrows – rage in his heart, Bent upon vengeance. To the fleet he came As darkly as the night; and he knelt apart And loosed off an arrow – lashed and clanged The doom-knelling string upon the silver bow. He struck first the mules and the swift-limbed dogs, And then vengefully at men sent his venomed darts, And mounded up the corpses on cremation-pyres.

This has little in common with the second instance, the descent of Athena into the assembly of the Greeks in order to dissuade Achilles from slaying Agamemnon:

And so spear-poised Athena, standing behind him* – Appearing yet to none of them, apart from him – Now grabbed him by his gold hair. Jarred, he turned, And knew her in an instant by her eyes that flashed As terrible as lightning. And thus he spoke to her With feather-fletched words**: "Why have you come, O daughter of the aegis-bearer, all-wise Zeus? Would you witness for yourself the wanton abuses Of Atrides*** Agamemnon? I tell you for sure, His arrogance may lose him even his life." (* i.e. Achilles) (** Greek ἔπεα πτερόεντα, presumably 'words flying like arrows', but not apparently 'winged words' in the modern literary sense of 'proverbial or memorable words') (*** i.e. 'son of Atreus')

This in turn does not much resemble the rising of Thetis from the sea in response to the complaints of her son Achilles:

So he spoke, so he wept, and it went to the lady Who bides beneath the waves in abysses of ocean With her ancient father. From the hoar-grey flood She suddenly ascended like a shrouding mist. And she sat there as he wept, and she wiped his tears; And then saying out his name, she spoke these words: "Why weeps my son? And what is your distress? Speak and do not hide it. Share it with me."

A moment ago I mentioned the chasm between theory and practice, and it must be said that these few snippets of literary translation can do little to help us get across it. Indeed, even the whole translation (which, remember, consists only of the first book) would not do much to fill in the gap.

But suppose that we had the whole Homeric corpus before us, translated into our own meter (or one close to it) with maximum fidelity to formulas, and perhaps also annotated so as to highlight the progression of traditional themes. In the course of reading through the verses, preferably aloud, one would naturally pick up on the repetitions and patterns. Perhaps additional information – such as summaries and fragments of the Epic Cycle – could be supplied as appendices, so that the reader gets a feel for the multiplicity of alternate narratives that is the hallmark of oral tradition.

This material could then be used as the basis for a simple exercise. Without trying to memorize the text verbatim, nor going out of your way to be individually innovative, select some scene or event or stretch of narrative and try to retell it in your own words while retaining the meter and style of language. (Bonus points if you set it to a melody and sing it to the lyre!) You can start with mere retelling, and progress to the harder task of lengthening by embellishment or digression, perhaps throwing in some of the alternative material known to you. Finally you might dare the retelling of traditional stories lost to literature – in this case the judgement of Paris, the abduction of Helen, the fights with Penthesilea and Memnon, etc. etc.

Our practice of this exercise is hindered by the lack of a suitable translation of the Homeric material. But in the course of my experimentation (not 10% of which gets scrubbed up and posted on this blog) I have tried it many times with Beowulf. My method is to select one of the forty-three fitts at random, take a quick look through my written translation (for which might easily be substituted the metrical translation of Francis Gummere) without trying to memorize it exactly, recompose the fitt orally with varying degrees of fidelity and digression, and record the whole thing so that it can be played back and scored for fluency and general success.

Having also tried blind improvization, I can say for sure that this method is much easier, because the reader (and more so the translator) of Beowulf becomes habituated to a number of repeated formulas that can be handily employed to keep the narrative flowing. But as we know, Old English poetry stands at some distance from oral tradition and so lacks fully developed themes, and it is these that (I suspect) constitute the true key to the locked door of recompositional epic. Yet until I can either learn Ancient Greek (or Serbo-Croatian), or convert someone who knows it and has plenty of time on his hands to the noble cause of tradpoetry, that key remains lost and there is no easy way to begin looking for it.

The World-Hoard

Does this mean, then, that we cannot hope to enter the house? I would reply no, because that house has a ‘lower’ door as well as a ‘higher’ one, into which it is somewhat easier for uncultured riffraff to steal. It is hoped, of course, that both will be unlocked in time so that we may pass through all rooms freely.

To use a different but similar metaphor – the one with which we started – the absence of thematic ‘furniture’ and ‘objects’ from the house of our collective memory can be remedied by the expedient of making what things we need for ourselves. And this is not in any way incompatible with our long-term plan to buy expensive antiques at auction.

Is it feasible to create, consciously and deliberately, a poetic theme? Or did the ones that we find fully developed in our earliest texts arise by some sort of blind evolutionary process? Being the careful scholars that they are, oral theorists are not much inclined to speculate on this question. Parry ventures much further than most in one of his articles on Homeric diction and style (emphasis added):

The poet who composes with only the spoken word a poem of any length must be able to fit his words into the mould of his verse after a fixed pattern. Unlike the poet who writes out his lines – or even dictates them – he cannot think without hurry about his next word, nor change what he has made, nor, before going on, read over what he has just written. Even if one wished to imagine him making his verses alone, one could not suppose the slow finding of the next word, the pondering of the verses just made, the memorizing of each verse. Even though the poet have an unusual memory, he cannot, without paper, make of his own words a poem of any length. He must have for his use word-groups all made to fit his verse and tell what he has to tell. In composing he will do no more than put together for his needs phrases which he has often heard or used himself, and which, grouping themselves in accordance with a fixed pattern of thought, come naturally to make the sentence and the verse; and he will recall his poem easily, when he wishes to say it over, because he will be guided anew by the same play of words and phrases as before. The style of such poetry is in many ways very unlike that to which we are used. The oral poet expresses only ideas for which he has a fixed means of expression. He is by no means the servant of his diction: he can put his phrases together in an endless number of ways; but still they set bounds and forbid him the search of a style which would be altogether his own. For the style which he uses is not his at all: it is the creation of a long line of poets or even of an entire people. No one man could get together any but the smallest part of the diction which is needed for making verses orally, and which is made of a really vast number of word-groups each of which serves two ends: it expresses a given idea in fitting terms and fills just the space in the verse which allows it to be joined to the phrases which go before and after and which, with it, make the sentence. As one poet finds a phrase which is both pleasing and easily used, the group takes it up, and its survival is a further proving of these two prime qualities. It is the sum of single phrases thus found, tried, and kept which makes up the diction.

This ‘evolutionist’ account is pure conjecture, based on Parry’s observations of Homer, and narrowly applicable to recompositional poetry (i.e. poetry composed in performance on the basis of traditional models). As Ruth Finnegan points out in her book Oral Poetry, many oral traditions are not recompositional but memorial (i.e. based on composition and retention of verses in memory without the use of writing); and though it may not be possible to say which type of composition preceded the other, this at least opens up the possibility of a ‘creationist’ account of poetic diction, in which it is first created by memorizing poets and only later subjected to the evolutionary pressures of recomposition. That it is wrong to say that a poet “cannot without paper make of his own words a poem of any length” should have been obvious to me from the start, as before I had even heard of oral theory I had successfully composed and retained hundreds of lines of verse in pure memory without the use of writing. And yet such ideas as these led me wrong for a long time.

Influenced early on by this passage (which of course was never intended to be used as a revivalist manual), and by the general bias towards the verbal side of poetry in oral theory, I somehow acquired the notion that the way to learn recomposition was to keep failing at blind improvization until I had “found, tried and kept” enough “single phrases” to make a success of it. To a certain extent, this does work; but it is like trying to learn how to swim by continually jumping into a fast-running river, without ever being able to practice in a calmer pool. When I recently decided that I had to break with this approach – having clung to it for far too long – it was the concept of the theme that came to the rescue.

While a story is retained in memory as a logical thread, and a phrase as an item of language8, a theme can be grasped as a cluster of ideas and imagery that may or may not be expressed in the same words each time it is recalled.9 Although some such clusters can scarcely be imagined except in the context of a story – and these are those that, to use Lord’s phrase, exist for the sake of the song – others seem to form the basic and universal stuff of the imaginative ‘world-hoard’ shared by poets in the same tradition. Here I am thinking particularly of descriptive themes – which, I propose, can to some extent be distilled independently of stories, by refracting direct sense-experience and mental imagery through poetic language and meter.

It is worth emphasising the point that these themes begin with images, not words, although the idea is to associate those images with a more or less stable set of poetic phrases. The images ought to succeed each other in a logical order, or at least an order that can be memorized easily, albeit one from which digressions and expansions might be made. For example: a theme concerning the sea might begin with waves crashing against the coastline, then move out into the middle of the ocean, then under the water, and finally across it.

One meaningful way to recite such a theme is by invocation, like so:

O Sea remurmuring, sink of all rivers, Brine untillable, bowl of thirst, World-binding serpent. Sieging the land, Flinging forth the fury of frothing waves; Sucking back thy substance through skittering pebbles And snaking rivulets, to sway and lurch And advance again more violently, unvanquishable. I have heard that on the out-ocean, howling winds Whip up the waters into wild tempests; Clouds gather gloomily; the crack of lightning Rakes across the rugged waves as rain comes sheeting. What misery they suffer then, the men who cling To the timbers and the rigging of some tumbling boat: Sea-weary, salt-sick, no shelter finding On the endlessness of ocean, the emptiest waste. Should they be wracked against the reefs, and through ruptured timbers The tides come unstoppable in swirling torrents, They must brave then the brine – lest the abode of the homeless, In concentric circles sucking them down, Should drag them to their deaths on its dark journey Through the lightless fathoms to the lowest abyss. Their corpses shall be bloated in the cannibal sea And their flesh be feasted on by fish-battalions: Wide-grinning sharks, and worm-armed squids, And their eyes shall be eaten by the armoured crabs. Hide from me that night-mere; haste my journey With favourable weather and a following wind – So the fast-cutting keel traverses swiftly, Skimming lightly on the liquid paths; Floating foam-prowed; flying like a bird; To draw into the bay, and to drop its anchor. Then we stride upon the beach-sands; slipping the embrace Of land-lapping waters, locked in tide-chains, Lulled into laziness by languid breezes, Dusk-blue wilderness, depth unconquered, Measureless, untillable, remurmuring Sea.

One good reason to recite such verses, in the event that you are travelling over water, is that they constitute a ritual expression of the principle of ‘stating the worst and wishing for the best’. (And if that is all too irrational for you, consider the sea as an analogy of everything dark and unconscious that has to be crossed successfully.) But from the purely functional perspective, what we are doing by such recital is conjuring mental images of the sea and putting them into poetic phrases, and these can only come in handy when recomposing any narrative that involves the common themes of sea-passage and sea-proximity. By continually recalling the images, and contracting or expanding upon them in phrases as dictated by the ebb and flow of the imagination – as opposed to simply memorizing the phrases verbatim – we also gently accustom ourselves to the element of improvization involved in this.10

This thematic technique is one that I have only recently hit upon, so I don’t want to lay it down as a law. But so far, the results have been promising: the themes seem to work in the heat of recomposition much as karate katas (i.e. memorized and repetitively drilled arsenals of techniques) are meant to work in an actual fight.11 Other fundamental themes that I have worked out and practiced concern the sun and four seasons, as well as the earth and its various woods, fields and other landscapes, which can be expanded into catalogues of beasts and trees; others yet untouched might describe the appearance and character of different types of men and women, much as in the Eddic Lay of Rig; and I have even created one theme in ‘Dantean’ fashion12 by memorizing the layout of a certain place and expanding upon it in imagination. Of course, there is no question of building up a full ‘world-hoard’ individually; and since many themes are beyond my ken and that of most people, one holds out hope that tradpoetry will one day become widespread, so that they might be poetized and handed down by those who can speak with experience upon them.13

As I’ve briefly mentioned, I daresay a case could be made for the emergence of historical recompositional traditions out of just such ‘primitive’ invocatory and schematic oral themes.14 But to attempt this here would not only overbloat this post but also distract us from our main concern, which is practicality. Unless some as-yet-unforeseen theoretical cloud should loom up on the horizon, my top priority henceforth will be to demonstrate that the techniques worked out in all these lengthy essays on poetics actually hold up in practice. Stay tuned for the results…

Note that Havelock makes a number of claims about traditional poetry that are questionable or downright wrong. These discolour his metaphor to a certain extent; for example, as we shall see, the themes of Homer are not so static and undynamic as to be truly comparable to items of furniture. He also claims that Homer invented the story of the Iliad as a convenient means of showcasing his ‘tribal encyclopedia’, but this notion is not supported by the evidence. At least some of the patterns underlaying traditional stories are very ancient, or perhaps perennial, in nature: one example would be the Return Story, in which a hero goes home to a wife who turns out to be either faithful or treacherous, which was attached to Odysseus and Agamemnon in Greek antiquity but was found by Parry and Lord to recur in South Slavic epic poetry as well.

Lord distinguishes motifs from themes in Singer of Tales (p443-4, online version) as follows: “I should prefer to designate as motifs what they [i.e. Francis Magoun and others] call themes and to reserve the term theme for a structural unit that has a semantic essence but can never be divorced from its form, even if its form be constantly variable and multiform.”

In Foley’s parlance, this constitutes its ‘traditional referentiality’, the deeper and more obscure layer of meaning that accumulates in a phrase or theme (or even, one imagines, a story-pattern) as a result of all of its previous uses in context.

This is a rather intriguing statement on which Lord, unfortunately, did not elaborate.

I’m not impugning Pound’s knowledge of Ancient Greek, but referring primarily to his treatment of Chinese literary poetry such as that of Li Bai, which he translated into English without even a smattering of the original language (while also making it out to be some sort of prototypical free verse, despite the fact that it has both syllabic meter and end-rhyme).

This, of course, is not the only option for rendering Greek hexameters into an English meter suitable for tradpoetry. Were we intent upon the exact replication of Homeric formulas, we might have opted instead for the accentual six-foot line described in this post.

This is not to endorse the strict oral-theorist position that Homer could not possibly have written the Iliad and Odyssey. If we accept the legend of the blind bard at face value (and why shouldn’t we?), the safest bet would be that he dictated them to one or more literate scribes. Another possibility (entertained by Parry – see here, p.6) is that they were memorized by his followers and handed down in much the same way as the Rig-Veda. But none of what Parry observed in the style of the poems necessarily precludes his having written them out using more or less the same technique as in oral composition. Lord’s observation in Singer of Tales that literacy spells the kiss of death to oral tradition, based on his observation of the South Slavs, might be generalizable to the early medieval English but not to the Greeks of Homer’s time; literary culture is cumulative, and cannot do much to distort or damage oral culture until it has had considerable time to accumulate. To a South Slavic guslar, literacy was an initiation into modern culture and literary tradition; to an early English scop, it was an initiation into Latinate culture and Christian religion; but to Homer, it would have been nothing more than a useful technique for recording and refining the pre-existing oral culture of Greece, to which there was as yet no alternative. Even the “notion of the fixed text” singled out by Lord as the killer of oral tradition is only carried by writing, not inherent to it, like the malaria transmitted by but not innate to the mosquito.

Lord in Singer of Tales makes much of the fact that the South Slavic guslars used the word reč (‘word’) to refer to poetic phrases as well as ordinary words.

Not only have these clusters of collective imagination long been disintegrated by literacy and the ethos of constant individual innovation, they have since been replaced by the new clustered world-ideas of modern television and cinema (which, of course, still depend upon creative efforts of a collective nature). To build back a ‘world-hoard’ of poetic themes from traditional sources and direct experience is, needless to say, to reduce our dependence on this modern cultural slop industry and the class whose ideology everywhere pollutes it.

Since we cannot expect to learn in the same way as illiterate bards, without recourse to the written word, there is no real reason to avoid writing any of these themes down. But we should beware of ever (for want of a better word) reifying them through writing, turning our focus away from the capacity to recall them in memory and towards the external production of a literary artefact. One way to make sure that this change of focus does not take place is to only ever write down a basic form of a theme, for the purposes of aiding one’s memory where needed, while expanding and refining it much more outside the book.

A relevant personal experience comes to mind here. Once upon a time, I wanted to learn a certain language, and started using Anki to create a master deck of flashcards. I ended up deleting that deck, after it had absorbed countless hours of work, once it became clear to me that I had got into the habit of concentrating more on the compilation of words and phrases in Anki than on their retention in my own memory. In this context, my attitude was obviously irrational. But the same is considered all too reasonable when it comes to the creation of artistic works, whereas the notion of ‘introjecting’ one’s art is entirely alien.

This analogy is chosen above all to expose the foolishness of those moderns who would dismiss such poetic themes as concatenations of ‘clichés’. Such people are like martial arts students who want to learn only the flashiest moves, or demonstrate their natural virtuosity by innovations, without having to practice such banalities as basic punches and kicks.

By this I refer to the theory of Frances Yates that Dante’s Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso were mnemotechnic topoi, or ‘memory palaces’, filled with exemplars of virtues and vices. In her Art of Memory (p.95) she says the following:

That Dante’s Inferno could be regarded as a kind of memory system for memorising, Hell and its punishments with striking images on orders of places, will come as a great shock… It is by no means a crude approach, nor an impossible one. If one thinks of the poem as based on orders of places in Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, and as a cosmic order of places in which the spheres of Hell are the spheres of Heaven in reverse, it begins to appear as a summa of similitudes and exempla, ranged in order and set out upon the universe. And if one discovers that Prudence, under many diverse similitudes, is a leading symbolic theme of the poem, its three parts can be seen as memoria, remembering vices and their punishments in Hell, intelligentia, the use of the present for penitence and acquisition of virtue, and providentia, the looking forward to Heaven. In this interpretation, the principles of artificial memory, as understood in the Middle Ages, would stimulate the intense visualisation of many similitudes in the intense effort to hold in memory the scheme of salvation, and the complex network of virtues and vices and their rewards and punishments – the effect of a prudent man who uses memory as a part of Prudence.

You can find some discussion of this theory here.

I am thinking here especially of anything to do with specialist skills, such as seamanship and aviation, or basic aspects of modern warfare such as engaging in firefights. Homer in the Iliad and Odyssey narrates in detailed phrases many activities that may not have lain within his own range of capabilities – such as building a ship from scratch – and he may admittedly have drawn them from a very wide experience, or else from a fertile imagination. But assuming that his diction was truly drawn from a common stock (as maintained by Parry and others), one imagines that its themes and phrases were built up by the contributions of countless people from all walks of life who held some greater or lesser stake in the art of traditional poetry, which may have been practiced by a specialist class of bards but could not have been wholly restricted to them. Thus we might say – a little paradoxically – that while Homer may not have known how to build a ship from scratch, his poetic tradition did, and that it contained this knowledge because one or more shipwrights practiced it at some level of proficiency. For a new poetic tradition to function in this way, it would have to combine the widespreadness of rapping in black culture with the contempt for notions of ‘copyright’ and ‘plagiarism’ found in online meme culture.

Note in this connection that the memorized invocatory poems of the Rig-Veda predate the great Indian narrative epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, which (I assume) are more likely to represent the summation of a recompositional tradition. The order of precedence between the Homeric Hymns and the Iliad and Odyssey is less clear, but one imagines that the traditional matter concerning the gods would have predated that concerning the deeds of heroes and been more liable to memorial fixation. It may not may not be relevant here that in the Odyssey, the singer Demodocus is accompanied by dancers when he sings of the gods, but sings of heroes to a sitting audience – suggesting to me that material concerning the gods was more fixed than heroic epic, for dancers would require musical predictability, and the sitting audience would not want to be straining to hear the story above the din of the dancing. (For a speculative reconstruction of such Homeric dancing, see here.)